Many of us are familiar with the knock of a delivery driver bringing us takeaway food, groceries or our latest online splurge. Now, a company backed by Google’s owner is replacing the driver with a drone.

Wing is today launching a pilot program in Canberra, in tandem with major Australian supermarket Coles, to deliver groceries by drone to households in several suburbs.

It is pledging to fly the groceries to people within minutes of them ordering online.

If that sounds like a literal pie in the sky concept, Sydney University supply chain expert Professor Rico Merkert said the idea could take off widely within five years.

“I think this is what the future will look like, and it’s obviously not just happening in Australia, although Australia has been at the forefront,” he said.

“We’ve been trialling delivering coffee through to pizzas, and delivering pharmaceutical goods by air. Groceries [are] the next logical step.”

Globally, online retailers have been trialling similar ventures and pushing towards automated processes, including Chinese ecommerce giant Alibaba.

How do you deliver groceries by drone?

Wing is not flying groceries directly from Coles supermarkets.

Instead, it has a hub in Canberra that has been stocked up with 250 of the supermarket’s top-selling items. This is similar to the so-called ‘dark warehouse’ model currently being picked up by other tech startups targeting groceries.

People can order these items through a specially designed app.

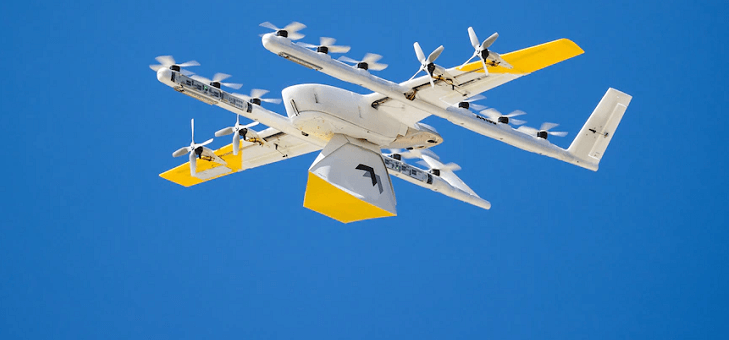

When an order comes in, Wing has packers ready to fulfil it. The drones are then sent up into the air, and flown to their delivery address using automated technology.

“The drone system is a type of autonomous system that maps the routes and schedules the flight,” Wing’s managing director, Simon Rossi, told the ABC.

“So we have live pilots monitoring the drones, but to all intents and purposes the system is autonomous.”

These pilots oversee up to 15 drones at once.

This is the latest collaboration to be announced by a major retailer to get Australians their groceries in record time. Analysts say the space is one to watch and could be worth $2 billion by 2025.

However, all of the other major ventures are using delivery drivers and riders.

When it comes to drone deliveries specifically, there are lots of logistical hurdles and privacy concerns for companies to overcome before the concept becomes a viable business.

You can’t get drone-delivered milk at night

Wing, which is owned by Google’s owner Alphabet, a leading US company, has been working on this area of research for a decade.

It has done similar pilots to the Coles idea with takeaway chains around Canberra and Logan in Queensland.

It had to get several exemptions from the Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA) to run those trials, and rules still affect when and how it can deliver.

For instance, its drones can only fly within 10 kilometres of their delivery hubs, and they can only deliver in the daytime.

“We don’t fly at night. We do fly in the rain and we can fly in fog and mist, but there is a point where the vision becomes limited, and that we would have to not fly in certain circumstances,” Mr Rossi said.

The drones can only carry 1.5kg at a time.

It is that limitation in particular that shows how making this profitable could be a tough endeavour for groceries, which are largely heavy, low-cost items.

“And so that means that the drone delivery service is probably not the one that’s going to be doing the weekly shop,” Mr Rossi added.

Is this even profitable?

At the moment, none of this is profitable for Wing. The money for the project is coming from Alphabet.

“We did 100,000 drone deliveries in Australia. And in the first two months of 2022 we’ve already surpassed that with another 30,000 deliveries,” Mr Rossi explained.

Sydney University is currently looking at the economic viability of drone deliveries in tandem with industry group iMove. It is looking at how all the issues including weather, weight and speed impact the model’s financial viability.

Prof. Merkert is heading up that study. He said the tipping point may not be as extreme as some may assume.

“It depends on what you’re ordering and what the margin on it is [to the retailer],” he said.

“Delivery via drones, particularly if it’s just in a small radius, could actually be cheaper than via truck or with the individual using his or her own car and driving to the shop.”

He thinks the minimum order to help make drone delivery viable could be as low as $10 or $20.

One thing that could improve viability would be automating the packing process. That would reduce the overheads of paying workers as well as speeding up operations.

Woolworths is currently doing this for its regular grocery distribution, with soon-to-be-built factories in Sydney and Melbourne planning to replace packers with robots, eliminating 700 jobs.

It gets complicated in dense locations

Wing’s pilot projects have been approved by CASA in relatively low-density locations, due to safety concerns about drones flying in busy airspaces.

“Certainly, our vision is to be able to have this service Melbourne or Sydney,” Wing’s Mr Rossi said.

“We need to be mindful of the safety aspects and, at the moment, we continue to work with CASA to continue to expand the service into areas where there is more air traffic.”

Prof. Merkert said other barriers to operating in dense cities included figuring out how to deliver with drones to apartment blocks that do not have clear space for landing.

At the moment, the rules are that drones have to land far away from people.

“There won’t be helicopter drone landing pads on all the buildings overnight,” he said.

“But what is possible is that there will be a little box or something in front of the building, where the drones can just deliver those items. And then there might be a concierge who will look after that stuff.”

He said he appreciated that drone delivered goods would never be for everybody.

“My wife really likes going down to the shops,” he added.

What about privacy concerns?

Mr Rossi said the drone’s cameras were for “navigational purposes only”.

“Whilst we deliver to a location, people’s confidential information isn’t identifiable in the flight or to the people that operate the flight,” he said.

Matthew Craven is a lawyer who specialises in technology and privacy law. His expertise is related to the privacy implications of drones, which fly over people’s houses with navigational cameras.

He said drones were unlikely to be capturing any vision of people that was identifiable, except those asking for home delivery.

“You’re looking at this top of someone’s head from 50 metres. Probably you can’t really work out who it is,” Mr Craven said.

“Some of the issues have been more the private small drone operators who are just buzzing around and causing mischief, or when no-one had any real privacy records.

“In a way, it’s good that it’s happening on a larger level because the organisations involved are subject to the Privacy Act.”

CASA’s licence of Wing’s operations encourages people to contact the company if they have concerns, or the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner.

Mr Craven said his interpretation of the technology, with its current weight and travel limitations, meant it may be best placed as a service to deliver things like medical supplies in remote areas.

“It might be that [it] ends up being more appropriate for high cost, low weight items that are needed very quickly,” he said.

“I’d probably [order groceries by drone] to see how it worked as a gimmick.

“If there was something I would get, it’d be a rapid test from the pharmacy. If we were locked down again, and my mum wasn’t around to drop one off.”

© 2020 Australian Broadcasting Corporation. All rights reserved.

© 2020 Australian Broadcasting Corporation. All rights reserved.

ABC Content Disclaimer