John Hawkins, University of Canberra

Few people expected the Reserve Bank to adjust its cash rate at its first meeting of the year today, and for good reason.

It has been saying loudly that it is “not expecting to increase the cash rate for at least three years“. Today it said the commitment extends to 2024.

But it isn’t a commitment not to cut the cash rate.

A further cut in the cash rate to take it below its present all-time low of 0.10 per cent would turn the cash rate negative.

The cash rate is that rate that banks pay to borrow money from each other.

It has always been positive, at times very positive.

Ten years ago it was 4.75 per cent. Then, as now, it was used to help set every other rate.

But there’s no reason why it couldn’t be negative. Borrowing (accepting deposits) entails costs. If the banks offered funds are offered more than they need, they’ll charge for accepting them.

Some rates are already negative

It’s already happened in the bond market. In several bond auctions, lenders to Australian government have agreed to pay for having the government accept their money.

Overseas, bond rates in Germany, Switzerland, Netherlands, Slovakia, Denmark, Austria, Finland, Belgium, France, Ireland, Slovenia and Lithuania are negative. In Germany it means that someone lending the German government 105 euros agrees to get back only 100 euros when the loan expires 10 years later.

In at least three countries, Japan, Denmark and Switzerland cash rates are also negative, at rates of -0.10 per cent, -0.60 per cent and -0.75 per cent.

In two other countries, the Bank of England and the Reserve Bank of New Zealand are talking with banks about how to make negative cash rates work.

Calculations I carried out with colleague Timothy Anderson suggest that if Australia’s Reserve Bank acted in accordance with its previous behaviour, it would have turned Australia’s cash rate briefly negative in the second half of last year.

There’s a case for negative cash rate here

Our model, that accurately describes previous Reserve Bank behaviour, is that the bank has a view about the ‘neutral’ cash rate, one that will leave the economy neither ‘too hot’ (too much inflation) nor ‘too cold’ (too much unemployment). If inflation remains too low (and/or unemployment too high) at the neutral rate it moves the cash rate below neutral until inflation climbs back up.

In August 2020 when the bank was forecasting a dire outlook with unemployment peaking at 10 per cent and inflation well below target our model suggests that if the bank was following previous practice it would have cut the cash rate to around -0.25 per cent.

By November 2020 when the bank’s forecasts were more positive, our model suggests a positive, but still extraordinarily low cash rate, of about the 0.10 per cent it adopted.

Australia’s Reserve Bank has been remarkably reluctant to take rates negative, seeing a cut into negative territory as fundamentally different to a cut that leaves rates positive.

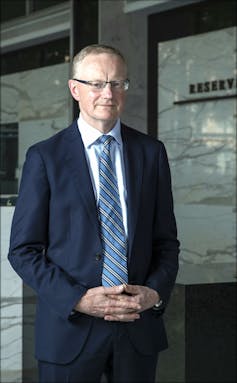

Governor Philip Lowe has repeatedly said that negative rates are “extraordinarily unlikely“.

But he has conceded he would have to consider them if the world’s other important central banks went negative, a contingency several of them are preparing for.

Economic studies suggest that the neutral rate has been heading downwards for decades and possibly centuries. If the trend continues, negative rates will eventually become widespread.

To not match negative rates elsewhere would be to invite an influx of ‘hot money’ chasing higher rates in Australia than were available elsewhere, pushing the Australian dollar uncomfortably high.

For now, the Reserve Bank has adopted a suite of other unconventional measures, such as lending cheaply to banks and buying government bonds, that it believes will have much the same effects as taking the cash rate negative.

Today it extended announced a decision to buy an additional $100 billion of bonds when the current bond purchase program expires in mid-April.

Governor Lowe will explain more in a televised address to the National Press Club on Wednesday.

Should things worsen here or overseas he might have to go further and overcome his reluctance to push the cash rate negative.

We don’t quite know what would happen

How a negative cash rate would play out depends on how the banks respond.

There are three possibilities.

First, the banks could adjust neither their deposit nor lending rates, meaning the negative cash rate had little effect.

Second, the banks adjust down both their deposit and loan interest rates, but this would mean charging depositors for placing funds with them, something banks haven’t done in other countries that have zero rates for fear of losing customers.

Third, banks could lower lending interest rates only. This might avoid unpopularity among customers but would erode interest margins. Over time banks might become less keen to lend.

It’s not clear what bank customers would do. In 2015, a survey conducted for ING Bank asked what savers would do if the deposit interest rate fell to minus 0.5 per cent.

Only 10 per cent said they would spend more, while 14 per cent said that they would save even more, 42 per cent said they would switch some or most of their savings to somewhere like the stock market and 21 per cent would move it to “a safe place”.![]()

John Hawkins, Senior Lecturer, Canberra School of Politics, Economics and Society, University of Canberra

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.

Do you think interest rates will go negative in Australia?

If you enjoy our content, don’t keep it to yourself. Share our free eNews with your friends and encourage them to sign up.

Related articles:

https://www.yourlifechoices.com.au/finance/is-it-time-to-get-a-financial-coach

https://www.yourlifechoices.com.au/finance/reuse-these-disposable-items-and-save

https://www.yourlifechoices.com.au/finance/news-finance/economic-survey-points-to-likely-rate-hike-by-2022