Caroline Osborne, University of the Sunshine Coast and Claudia Baldwin, University of the Sunshine Coast

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought into sharp focus the need for connection to our local community and the health challenges of the retirement village model.

We know that, as we age, most people prefer to stay in their own homes and communities instead of moving to retirement villages. Some have gone so far as to say retirement villages have had their day. However, the reality is not quite that simple.

The challenge is that seniors are not well informed on what they could demand of the market. Planning schemes could also do more to create incentives for the changes we need now.

The challenges are complex and urgent as the global population grows and ages. Yet our housing supply reveals a bad case of the tail wagging the dog. Finely tuned financial models and development processes are driving the housing products available in the market.

What’s needed instead is adaptable housing and neighbourhoods to help people as they move through life’s stages.

Are the days of the retirement village numbered?

Many individuals and families struggle to find the right ‘fit’ between the supported living options of retirement villages, independent living lifestyle villages and staying in the (often unsuitable) family home as their needs change.

Such villages offer viable products in the market as an important part of the housing mix. The models have some advantages in that they:

-

are thoroughly costed and provide a good return for developers

-

offer a range of living options to suit most budgets and level of care needs

-

promise security, activities and a sense of community.

Seniors are best placed to say what they need

However, our research with seniors in south-east Queensland revealed a desire to ‘age in neighbourhood’ and to have neighbourhoods with a mix of ages and building forms.

Planning schemes could drive this now by giving priority to, and providing incentives for, sustainable and accessible housing close to transport and other services.

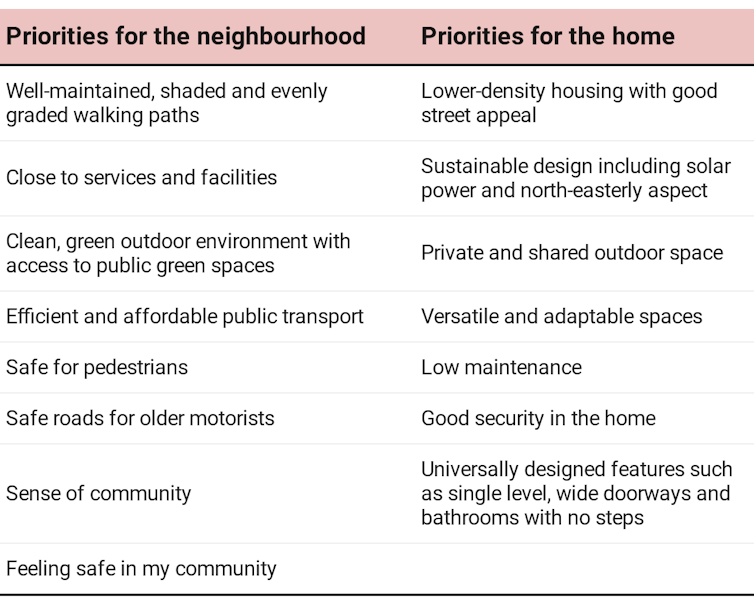

We worked with more than 42 seniors in south-east Queensland to design a series of housing types. These were based on what they told us were important to them in a home and a neighbourhood.

The table below summarises the key features that they told us make a neighbourhood and a home a good place to live as they age.

The resulting principles and housing types paint a vivid picture of what older people in a subtropical environment find appealing and supportive as they age.

Many participants preferred an accessible home on one level. Ideally, it should have two bedrooms and a study. This means it can easily be adapted to changing needs.

An essential component for our participants was to take advantage of the mild climate by having both private and shared outdoor spaces. Here they could socialise, relax and enjoy pleasant outlooks from the home. Cutting planning requirements for car parks by 50 per cent could add more shared outdoor space and cut housing and living costs for residents.

Homes should be sustainably designed. This means they capture natural light and prevailing breezes for through ventilation, take into account privacy and noise considerations in higher-density areas, and have solar and rainwater harvesting systems to save resources and money.

Also important was a neighbourhood with a variety of green, clean and safe public open spaces. This includes flat, well-maintained and shaded walkways for exercise and easy access to shops, facilities and public transport.

We then showed how all these housing types could be incorporated into one Brisbane suburb. This would mean seniors could remain in their neighbourhood in more suitable housing, reducing the stress of moving to unfamiliar surroundings.

How to make it happen

As with all complex challenges, everyone has a role to play in achieving these goals. However, local government planning reforms can act as a catalyst for the market to change and innovate.

Planning schemes could, for example, reduce application fees for developments that include accessible or universal design within 400–800 metres of key services, facilities and transport.

Carpark allocation could also be uncoupled from housing in locations close to transport and services. This would reduce the cost of housing and encourage greater used of active (cycling, walking, etc) and public transport.

This research clearly signals to local and state government, developers and small-scale property investors how houses, duplexes and mid-rise apartments could be put together in an age-friendly suburb. This transition to mixed-density infill development would support what we call ‘ageing in neighbourhood’.

Further, this research suggests planning ‘priority zones’ could give the market the incentive to invest in the future-focused neighbourhood development it should be providing to keep people connected to their community.

This article was co-authored by Phil Smith, Associate Director of Deicke Richards at the time of publication of the research report. Phil Smith is Director of Gomango Architects.![]()

Caroline Osborne, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Office of Community Engagement, University of the Sunshine Coast and Claudia Baldwin, Professor, Urban Design and Town Planning, Co-director, Sustainability Research Centre, University of the Sunshine Coast

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.