Ama Samarasinghe, RMIT University

Why would you dump a requirement for financial advisers to give advice that’s in their client’s best interests?

The findings about advisers in the landmark 2019 financial services royal commission couldn’t have been more stark.

Time after time, financial advisers were found to have:

- lacked skill and judgement

- proposed actions that benefitted the adviser

- been unwilling to find out whether poor advice had been given

- been unwilling to take timely steps to put bad advice right.

The result was a series of radical, but long-awaited changes in the industry, ranging from mandating a bachelor’s degree to enforcing ongoing professional development to introducing a legally enforceable code of ethics.

Around 10,000 of the industry’s 25,000 advisers left, most retail banks offloaded their advice arms, and the median annual fee for ongoing advice climbed 40 per cent from $2510 to $3529.

‘Best interests’ or ‘good advice’?

In response, ahead of this year’s election, then financial services minister Jane Hume commissioned a quality of advice review, which is due to hand its final report to new financial services minister Stephen Jones on Friday.

Ahead of its final report, the review has published 12 draft proposals intended to make advice more affordable and accessible.

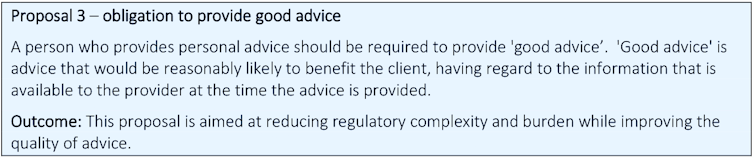

One of them would replace the present requirement for advisers to give advice that is in their clients ‘best interests’ with advice that is merely ‘good advice’.

If that is what the review recommends, and if the recommendation is adopted, while stand-alone financial planners would still be required to provide advice that was in their client’s best interests (because of their code of ethics), banks, super funds and other providers would be able to give a lesser standard of advice.

The core justification is reducing “regulatory complexity and burden while improving the quality of advice”.

While it would certainly aid in reducing the compliance burden, and would make advice more accessible, it isn’t obvious that it would improve the quality of advice.

Poorly defined

The best interests duty requires advisers to put the client’s interests first, to make sure the advice is right for each particular client, and to warn the client if the advice is based on insufficient information.

‘Good advice’ is defined simply as advice “reasonably expected to benefit clients”. Unless better defined, it will be a definition that leaves a lot to interpretation.

What banks and super funds believe they “reasonably expect” to be best for their customers, might not necessarily align with what’s best for their customers.

While removing red tape is important, removing regulations that require advisers to act in their clients’ best interests might not be in their clients’ best interests.

On Friday, Stephen Jones will have to begin to consider whether ‘good advice’ is good enough. It’s not a decision he should take lightly.

Ama Samarasinghe, Lecturer, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.