The announcement by Gordon Legal of a class action to compensate victims of the government’s so-called robo-debt scheme is welcome, perhaps even groundbreaking.

Standing alongside class action litigator Peter Gordon at a press conference in parliament house on Tuesday, former opposition leader and shadow government services minister Bill Shorten said the legal veteran was the man who “took on big tobacco in America, took on asbestos cases, took on thalidomide compensation”.

Gordon said he only began looking at robo-debt when Shorten took over the portfolio in May and invited him to examine the government’s curious behaviour of wiping the debts at the centre of legal challenges rather than pursuing them and establishing its right to the money in court.

What is robo-debt?

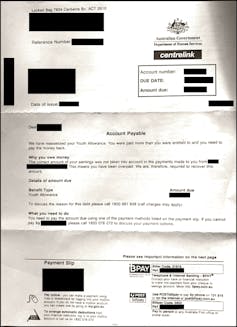

Robodebt letter. Supplied

Robo-debt is a part-automated process in which recipients of government benefits are sent letters asserting that they owe the government money because they have been overpaid. Many of the debts are false or highly inflated because they are calculated using an inaccurate formula that averages employment earnings over a series of fortnights rather than identifying what actually earned in the relevant fortnight.

Robo-debts have been routinely overturned as lacking a legal foundation when appealed to the first level of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal. Although the rulings have always been accepted by Centrelink in the individual cases taken before the Tribunal, Centrelink has not applied them to cases not taken to the tribunal.

Nor has Centrelink ever challenged those individual rulings at the second level of the tribunal, where the hearing and the reasons for decision are made public.

A Federal Court challenge by two Australians who are arguing the illegality of robo-debts remains underway, but Centrelink wiped both debts after the case was launched. Argument remains about whether this means there is still a live legal issue to be heard. The case is not expected to return to court until December.

What is “unjust enrichment”?

What is incontrovertible is that very large sums of money are being raised by a scheme that verges on extortion. “Unjust enrichment” is the term Gordon Legal plans to use in the action, a term that applies when one entity is enriched at the expense of another in circumstances the law sees as unjust.

It is also investigating whether the so-called collection fees levied by Centrelink should be refunded and whether those who have wrongly paid all or part of the amounts claimed should be paid interest on the amounts collected and whether they are entitled to compensation.

Between July 2016 and March 2019 the government issued 500,281 robo-debt notices, asserting debts of A$1.25 billion, with the average being $2,184, but not uncommonly as much as $10,000.

Much less has as yet been collected, but tax return garnishees, debt collection agencies and staff “quotas” are driving it up.

What’s different about the class action?

The class action differs from Administrative Appeals Tribunal reviews or Federal court actions by seeking remedies for a whole class of people, not only those with the knowledge or personal stamina to lodge an appeal.

It is form of legal process that cannot be stopped or slowed by wiping the debts of a few individuals. Being a judicial process, it is aired in public (first-tier tribunal decisions remain private).

What’s being claimed?

The simple argument that will be put is that the government has obtained monies to which it was not lawfully entitled. Not having a lawful basis for the collections (their being, in a sense, an unwarranted “tax” on the supposed debtors), it will be argued that it should return (“restitute”) the monies and pay damages as compensation for unjust enrichment.

There are a number of special features and technical requirements to be satisfied before a class action can successfully be lodged for consideration, including obtaining a sufficient number of plaintiffs.

Where to now?

It is still very early days. There are many procedural and legal hurdles yet to be crossed.

However, unlike the paths trodden to date, the class action holds the potential of being able to deliver justice to the many rather than to the few who win private victories without ever testing the government’s powers in open court.

Read more: Danger! Election 2016 delivered us Robodebt. Promises can have consequences ![]()

Terry Carney, Emeritus Professor of Law, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

If you enjoy our content, don’t keep it to yourself. Share our free eNews with your friends and encourage them to sign up.

Related articles:

Calls for urgent pension review

Rent assistance increase

Low income health care card changes