Andrea Carson, La Trobe University; Aaron Martin, The University of Melbourne; Andrew Gibbons, University of Texas at Austin, and Justin Phillips, University of Waikato

With a federal election expected in May, at a time of great upheaval at home and around the world, the need for trusted media to accurately inform voters’ choices and debunk myths will be critical.

Yet studies show about two-thirds of Australians are worried about misinformation, especially about COVID-19, and do not know who or what to trust.

This is further complicated when politicians are the culprits, making false claims in the news media and online.

So what role should journalists play in calling out these falsehoods? Or should this role be left to third parties, such as independent fact-checkers, to test verifiable claims?

The fight against ‘fake news’

Fact-checking is one global response to countering fake news, which has become a multi-billion-dollar industry. More than 340 fact-checking outlets now operate worldwide.

In Australia, independent fact-checkers include newswires AAP and AFP, and RMIT ABC Fact Check (a collaboration between RMIT University and the public broadcaster). Yet little is known about what effect independent fact-checking has on public trust in news where false claims can be found.

In a new study published in a major international journal, we investigate if third-party fact-checking affects public trust in news. To do this we used the case study of the ‘sports rorts‘ scandal.

As a quick refresher, the sports rorts scandal unfolded just before the 2019 federal election. Sporting clubs in Coalition and marginal seats disproportionately benefitted from a taxpayer-funded community sports grants program.

The Australian National Audit Office later investigated the funding process. It found the then sports minister and National Party deputy, Bridget McKenzie, had not allocated funds based on independent advice given to her. Several senior ministers, including Peter Dutton, defended McKenzie’s actions before she was forced to resign from that role because of the alleged pork-barrelling.

Marc Tewksbury/AAP

We use this real-life example in an experimental design to see what impact a real AAP fact-check about the scandal had on Australians’ trust in news. We mocked up two news stories – one presented as being from ABC online and another from News Corp’s news.com.au. The stories contained identical wording and headlines, but used different fonts and banners.

Both stories contained a real quote from the then home affairs minister, Peter Dutton, about McKenzie’s decision-making process. On 23 January 2020, Dutton stated:

Bridget McKenzie made recommendations, as I understand it, on advice from the sporting body that these programs that have been funded were recommended.

Dutton restated this position in other media that week, including on Nine’s Today program, suggesting his words were not a slip of the tongue.

The AAP fact-checked the statement and labelled it “false”.

Months after the scandal subsided, public recall of specific details was likely overtaken by pandemic news stories. So, we invited 1600 adult Australians to do an online survey and randomly assigned them to read either our constructed ABC or News Corp story, and then answer questions about the trustworthiness of that story (and the media outlet more generally). We randomly assigned half the respondents to also read the AAP fact-check.

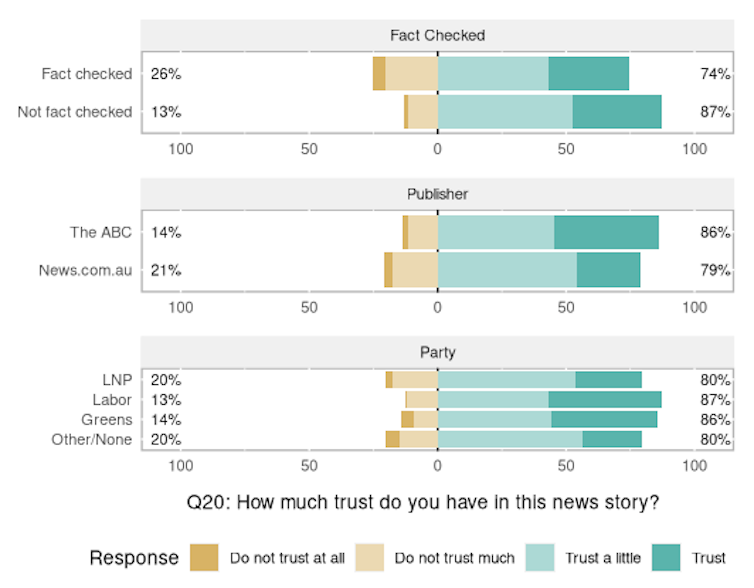

The findings tell both a positive and negative story about how Australians view political news. On the up side, trust in the news story (without seeing the fact-check) was high for both our ABC (86 per cent) and news.com.au stories (79 per cent). Political partisanship has some impact, with Labor supporters the most trusting of the news story overall (87 per cent).

Consistent with other Australian surveys, we found the ABC had higher levels of public trust overall than News Corp. However, some strong Coalition and right-wing supporters had greater trust in the news.com.au story, as other research has also found.

Concerningly, we found that when participants read the AAP fact-check after reading the news story, trust in the original story fell sharply (by 13 per cent overall), even after respondents’ political or news source preferences were taken into account. Counter-intuitively, the act of fact-checking had a clear negative influence on readers’ trust in the original news story for both the abc.com.au and new.com.au stories as the chart below shows.

Authors

This suggests news audiences may not separate a politician’s false claims within a news story from the news reporting itself. Think about that for a second:

- the politician told a falsehood

- a fact-checker corrects it

- but, as a consequence, the news story itself suffers the loss of public trust.

This finding is particularly important given Australian journalists’ reliance on a ‘he said/she said’ news reporting style (this excludes opinion pieces), in which readers are presented with competing statements, one or both of which may be false, rather than the reporter actively adjudicating the false claim.

In this case, letting fact-checkers determine the truth may be a deeply unwise strategy for journalism. While fact-checkers unquestionably do many positive things such as identify misinformation, in this instance it lowered trust in political journalism.

With the public demanding the truth, it seems journalists have a very important role to play by critiquing politicians’ false claims in news stories at the time of reporting.

While some outlets like Crikey already practise active adjudication in political stories, we acknowledge it might be problematic for an organisation like the ABC, which has impartiality as a duty in the ABC Act 1983.

However, the ABC’s 2019 revised code of practice specifies that “impartiality” does not mean every perspective receives equal attention. Other media have the same policy. For example, The Conversation’s approach to reporting climate change has decided in favour of the scientific evidence and does not give air time to climate denialism.

We see lessons in our findings for independent fact-checkers as well. Fact-checkers might help increase trust in news by more clearly stating they are fact-checking a politician’s specific claim, rather than the media coverage that contains it. Some fact-checkers make this distinction already on their websites, but rarely on every fact-check explanation.

Spelling this out may help audiences avoid conflating a fact-check of a specific political falsehood with the trustworthiness of the news story and media outlet.

With a federal election just months away, this study is a timely reminder of the important role that political journalists can play as sense-makers rather than just conveyers of political information.

Andrea Carson, Associate Professor, Department of Politics, Media and Philosophy, La Trobe University; Aaron Martin, Associate Professor, School of Social and Political Sciences, The University of Melbourne; Andrew Gibbons, Postdoctoral Fellow, Edward A. Clark Center for Australian and New Zealand Studies, University of Texas at Austin, and Justin Phillips, Senior lecturer, University of Waikato

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.

If you enjoy our content, don’t keep it to yourself. Share our free eNews with your friends and encourage them to sign up.