Kate Griffiths, Grattan Institute; Anika Stobart, Grattan Institute, and Danielle Wood, Grattan Institute

If you watch TV or read the paper, you’ve probably seen ads spruiking the achievements of the federal or state government – from the next big transport project to how they’re reducing the cost of living. While some government ads are needed, many are little more than thinly disguised political ads on the public dime.

A new Grattan Institute report shows both Coalition and Labor governments, at federal and state levels, use taxpayer-funded advertising for political purposes. But there is a way to stop this blatant misuse of public money.

Why do taxpayers fund advertising?

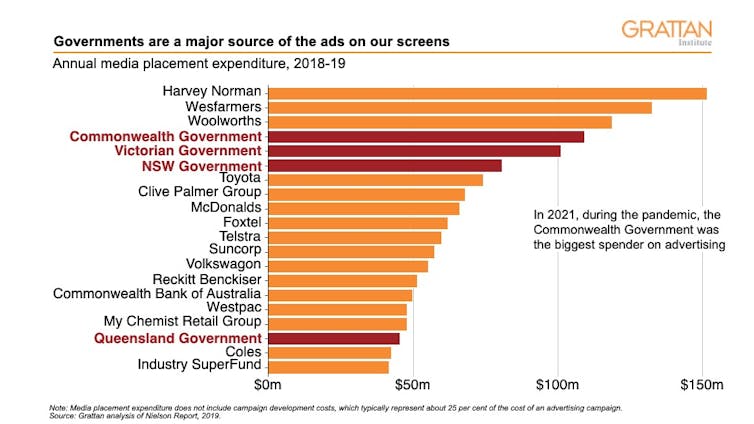

Federal and state governments combined spend nearly $450 million each year on advertising. And the federal, NSW, and Victorian governments individually spend more than many large private companies such as McDonald’s, Coles, and the big banks (Figure 1).

Governments run advertising campaigns to communicate important public messages and to ask us to take action. For example, in recent years we’ve seen a lot of federal and state government advertising about COVID-19 restrictions and how to get vaccinated.

These health messages are in our individual and collective interests, so it is appropriate that governments communicate those sorts of messages and that we – the community – fund them. But this is not true of all taxpayer-funded advertising.

Governments take advantage of this pot of money

Our analysis of every federal government advertising campaign over the past 13 years reveals that many were politicised. On average, nearly $50 million each year was spent on campaigns that conferred a political advantage on the government of the day – about a quarter of total annual spending.

Taxpayer-funded advertising is never as overtly political as party-funded advertising, but it still often contains elements aimed at securing an electoral advantage. The three main signs of politicisation we identified in federal and state government advertising were:

-

campaign materials that included political statements, party slogans, or party colour schemes. For example, before the last federal election, the federal government published ads in major newspapers that used the Liberal Party blue, alongside a vague statement: “Australia’s economic plan. We’re taking the next step”

-

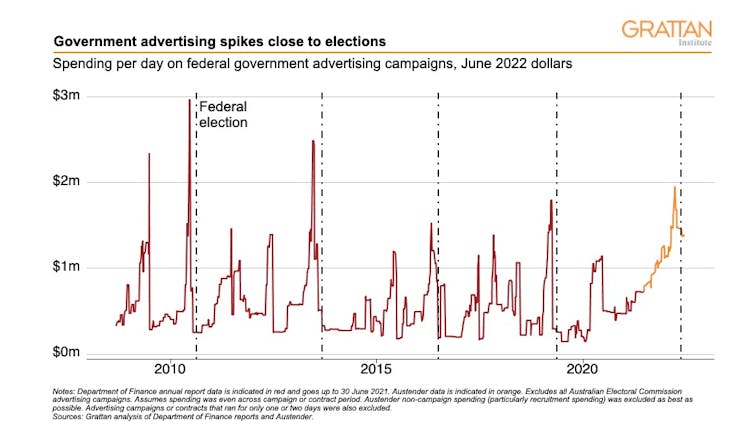

campaigns that were timed to run in the lead-up to an election, without any obvious policy reason for the timing. Spending on government advertising consistently spikes in the lead-up to federal elections (see Figure 2)

-

campaigns that spruiked the government’s policies or performance and lacked a meaningful call to action. For example, the Queensland government spent more than $8 million on two campaigns in an election year to “inform Queenslanders of the state’s recovery plan”.

Many federal and state campaigns contained multiple elements of politicisation – using party colours, spruiking government achievements, and running on election eve.

How to depoliticise government advertising

Taxpayers should not be footing the bill for political messages. It’s a waste of public money, it undermines trust in important government messaging, and it can create an uneven playing field in elections.

In the lead-up to the 2019 election, the federal government spent about $85 million of taxpayers’ money on politicised campaigns – on par with the combined spend by political parties on TV, print, and radio advertising. Oppositions, minor parties, and independents have no such opportunity to exploit public money for saturation coverage.

There are plenty of other ways governments can spruik their policies without drawing on the public purse. Ministers can use parliament, doorstop interviews, traditional media, and their own large social media reach to promote their policies. And if governments want to convey a political message outside those channels, they can advertise using party funds.

We recommend stronger rules to limit the scope of taxpayer-funded advertising. Campaigns should run only if they encourage specific actions or seek to drive behaviour change in the public interest. This would allow recruitment ads, tourism campaigns, bushfire or workplace safety campaigns, and anti-smoking ads – to give a few examples. But it would not allow ads that simply promote government policies.

Campaign materials should obviously not promote a party, or the government. And campaigns should run when they will be most effective, not when they will provide a political advantage (such as immediately before an election).

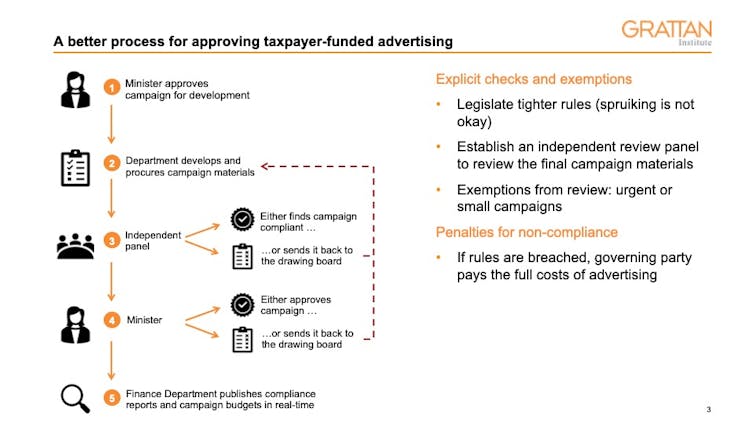

These rules should be enforced by an independent panel, which would check the final campaign materials. The panel should have the power to knock back campaigns that are not compliant – whether they are politicised, or more generally don’t offer value for money (see Figure 3).

Finally, we recommend a simple but strong penalty for breaking the rules: the governing party, not taxpayers, should be liable to pay the costs of any advertising that has not been ticked off by the independent panel. This would discourage governments from subverting good process, and provide a stronger safeguard against misuse of public money.

Kate Griffiths, Deputy Program Director, Grattan Institute; Anika Stobart, Senior Associate, Grattan Institute, and Danielle Wood, Chief executive officer, Grattan Institute

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.

Do you think political ads have gotten out of control? Or are they a necessary evil of our democracy? Let us know what you think in the comments section below.