Albert Van Dijk, Australian National University

When the clocked ticked over to 2020, Australia was in the grip of a brutal drought and unprecedented bushfires. But in the months since, while many of us were indoors avoiding the pandemic, nature has started its slow recovery. That is the message of our new analysis released yesterday.

Every year, my colleagues and I collate a vast number of measurements made by satellites, field sensors and people. We process the data and combine them into a consistent picture of the state of our environment.

Our 2019 report documented a disaster year of record heat, drought, and bushfires. We repeated the analysis after the first half of 2020, keen to see how our environment was recovering.

It’s not all good news. But encouragingly, our results show most of the country has started to bounce back from drought and fire. Here are four ways that’s happening.

1. Rain

Whether a region is in drought depends on the measure used: rainfall, river flows, reservoir storage, soil water availability or cropping conditions. On top of that, Australia is a vast country with large differences between regions.

By most measures, and for most of the country, wetter weather in 2020 helped ease drought conditions – although with caveats and notable exceptions.

Halfway through January, rain-blocking conditions in the Indian Ocean finally relented. This allowed the long-awaited monsoon to reach northern Australia, and encouraged more rainfall across the rest of the continent. February and March brought much needed rains in south-east Australia.

A young girl checks a rain gauge as her mum watches on at the family farm in February this year. Recent rainfall has eased drought conditions in parts of Australia. Peter Lorimer/AAP

A young girl checks a rain gauge as her mum watches on at the family farm in February this year. Recent rainfall has eased drought conditions in parts of Australia. Peter Lorimer/AAP

2. Water availability

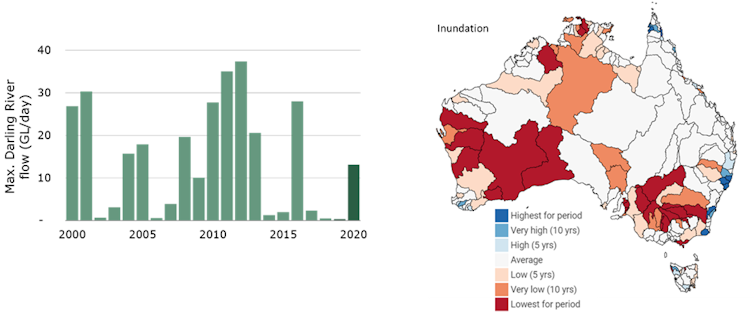

Across the continent, the volume of water flowing into rivers in the first half of 2020 was almost four times greater than the previous year – although still below average. Good rains fell in the northern Murray-Darling Basin. Some made it into the town and irrigation water supplies that ran empty during the drought, and storage levels showed a modest improvement by the end of June to 17 per cent of capacity.

The flows were also enough to fill wetlands such as Narran Lakes and the Paroo and Bulloo River wetlands, west of Bourke. There were enough flood waters left to send a modest flood pulse down the Darling River in March for the first time since 2016.

Maximum measured daily flow in the Darling River at Wilcannia (left) and the maximum extent of wetland inundation in the 12 months up to June 2020, compared to the period 2000–2019.

Maximum measured daily flow in the Darling River at Wilcannia (left) and the maximum extent of wetland inundation in the 12 months up to June 2020, compared to the period 2000–2019.

Reservoir water storage across the entire the Murray-Darling Basin improved from 36 per cent of capacity at the end of June 2019 to 44 per cent a year later. Even so, by June 2020 dry conditions still persisted in the tributaries and wetlands of the middle and southern Murray-Darling Basin.

Storage in urban water supply systems increased for Sydney (52 per cent to 81 per cent) and Melbourne (50 per cent to 64 per cent) while remaining stable for Brisbane (66 per cent), Canberra (55 per cent) and Perth (41 per cent).

Meanwhile, lake and wetland extent across much of Western Australia remained at record or near-record low levels. Due to the poor northern monsoon, Lake Argyle – the massive dam lake supplying the Ord irrigation scheme in northern Australia – shrank to 38 per cent of capacity, a level not seen for several decades.

3. Soil moisture

Soil moisture acts like a bank account: rainfall makes deposits and plant roots make withdrawals. This makes soil moisture a useful measure of drought condition.

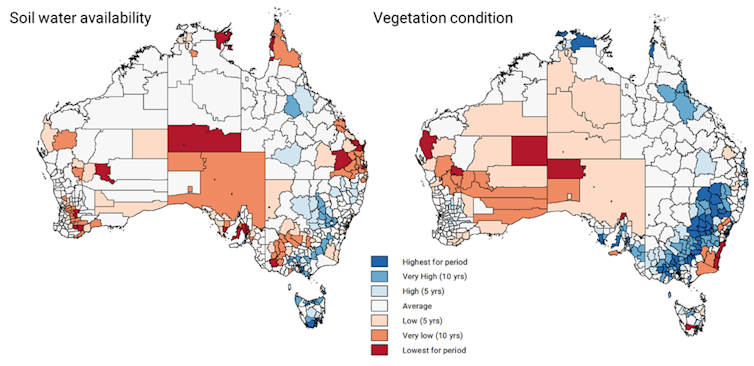

Average soil water availability across the country was far below average at the start of 2020, but returned closer to average conditions from March 2020 onwards. Very to extremely low soil water availability across most of north-west and south-east Australia had eased by June 2020.

By the end of June, rains had also improved growing conditions in south-east Queensland, western New South Wales, Victoria and South Australia. However, recovery in these regions is, literally, shallow. Soil water remains low in the deeper soil layers and groundwater from which trees and other drought-tolerant vegetation draw their water. Drought conditions also persist in the dry inland of Australia.

Average soil water availability and vegetation condition by local government area at the end of June 2020 in comparison to 2000−2019 conditions.

Average soil water availability and vegetation condition by local government area at the end of June 2020 in comparison to 2000−2019 conditions.

4. Vegetation growth

Vegetation condition is measured by estimating leaf area from satellite observations. National leaf area reached its lowest value in December 2019 due to drought and bushfires, but improved once the rains returned from February onwards. It’s remained very close to average since.

Autumn rains also brought the best growth conditions in many years across much of the eastern wheat and sheep belt. But in the Western Australian wheat belt, which did not see much rain, cropping conditions are average or below average.

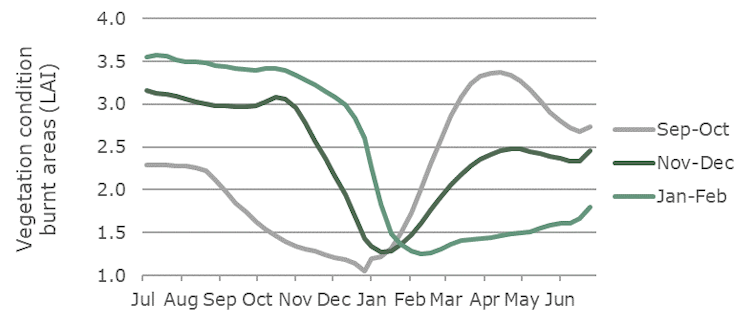

We separately measured vegetation recovery across areas in south-east Australia burnt at different times during the 2019–20 fire season.

In the central and northern NSW regions, which burnt earlier in the fire season and received plentiful rains, recovery was relatively swift – more than 63 per cent of lost leaf area had returned by June 2020.

Recovery of vegetation leaf area in areas burnt in Sept/Oct and Nov/Dec 2019 and in Jan/Feb 2020, respectively.

Recovery of vegetation leaf area in areas burnt in Sept/Oct and Nov/Dec 2019 and in Jan/Feb 2020, respectively.

But in the areas burnt in early 2020, recovery has been slow. The burnt forests in the far south of NSW and East Gippsland did not receive good rains until very recently. Also, much of the areas burnt in early 2020 are found in the mountains of the NSW – Victoria border region, where cool autumn and winter temperatures have paused plant growth until spring.

Leaf area recovery is not a good measure of biodiversity. Much of the increase will have been due to rapid leaf flush from fire tolerant trees and undergrowth, including weeds. Some damage to ecosystems and sensitive species will take many years to recover, while some species may well be lost forever.

Australia’s environment is bouncing back from a horrendous 2019. Marta Yebra/ANU

Australia’s environment is bouncing back from a horrendous 2019. Marta Yebra/ANU

Climate change: the biggest threat

Rainfall after June has been average to good across much of Australia, and La Niña conditions are predicted to bring further rain. So there is reason to hope our environment will get a chance to recover further from a horrendous 2019.

In the long term, climate change remains the greatest risk to our agriculture and ecosystems. Ever-increasing summer temperatures kill people, livestock and wildlife, dry out soil and vegetation, and increase fire risk. In 2020, high temperatures also caused the third mass coral bleaching event in the Great Barrier Reef in five years.

Decisive climate action is needed, in Australia and worldwide, if we’re to protect ourselves and our ecosystems from long-term decline.

Albert Van Dijk, Professor, Water and Landscape Dynamics, Fenner School of Environment & Society, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.

If you enjoy our content, don’t keep it to yourself. Share our free eNews with your friends and encourage them to sign up.

Related articles:

https://www.yourlifechoices.com.au/food-recipes/food/growing-vegies-in-containers

https://www.yourlifechoices.com.au/health/wellbeing/happiness-on-a-cold-day

https://www.yourlifechoices.com.au/health/wellbeing/printing-photos-good-for-the-soul