Australians are overwhelmingly planning on ageing at home – whether that be in a property they own or one they rent.

That was the conclusive result of the YourLifeChoices 2021 Older Australians Insights Survey, which drew more than 7000 responses. And given the frightening findings of the aged care royal commission, who could blame them?

Survey participants were asked where they intended to age. More than two-thirds (67 per cent) said at home, 8.3 per cent nominated a retirement community, 7 per cent said residential care and 3.2 per cent said with family.

Alarmingly, one in five (20.8 per cent) said they didn’t have a plan. It’s almost a ‘head-in-the sand’ view and given YourLifeChoices member feedback, we know a majority of older Australians simply do not want to think about what’s involved when the cracks first appear in their ability to live independently.

The Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety made 148 recommendations in its final report, calling for a new system underpinned by a rights-based act, funding based on need and much stronger regulation and transparency. Of course, such recommendations require adequate funding.

In the May Federal Budget, the government allocated $17.7 billion to the sector – but over five years –and provided an extra 80,000 home care packages – but over two years. Just 12 months ago, almost 103,000 were waiting for a package.

Read: Home care package waiting lists slammed as a ‘critical failure’

It acknowledged the need for extra staff and said it would spend more than $650 million to grow and upskill the aged care workforce. Staff shortages and movement of staff between aged care centres was a critical factor in the hundreds of deaths in aged care in the first year of the pandemic.

A report published in August by the Committee for Economic Development of Australia suggests that even without the minimum staffing standards set down by the royal commission, the nation’s aged care workforce needs to grow by an additional 17,000 workers per year between now and 2030.

But what of the complexity of both home and residential services?

Earlier this year, Peter Norden, the 71-year-old founder of Jesuit Social Services, prison reform advocate and honorary fellow at Deakin University, wrote of his first experience of navigating the aged care system after an operation.

“I’ve been working at a fairly high level – teaching and writing and research – and I couldn’t understand what it was all about,” Dr Norden wrote in The Age.

“When I started trying to change providers, there were so many barriers and hoops to jump through that you almost felt it was a waste of time; you make so many damn phone calls.

“I found it bureaucratic, complex and difficult to feel any sense of control or that I was a partner in this.”

Dr Norden is a member of the lobby group Aged Care Reform Now, created to give older Australians and their families a voice in the movement to change aged care.

Its mission is to ensure the recommendations of the royal commission translate into action.

“It seems to me it’s not just a shortage of money, it’s a system that needs to be reformed,” Dr Norden says.

“People who are not at a super-advanced stage like myself, whose brains still mostly operate okay, want to be able to use their own judgement to make choices, and to reallocate services as their needs change, not to be on a waiting list for a year or two.”

Mable, which describes itself as “a website that enables older Australians to connect with independent care and support workers in their local community”, is in furious agreement about the need for reform.

Read: At last, a common-sense approach to home care

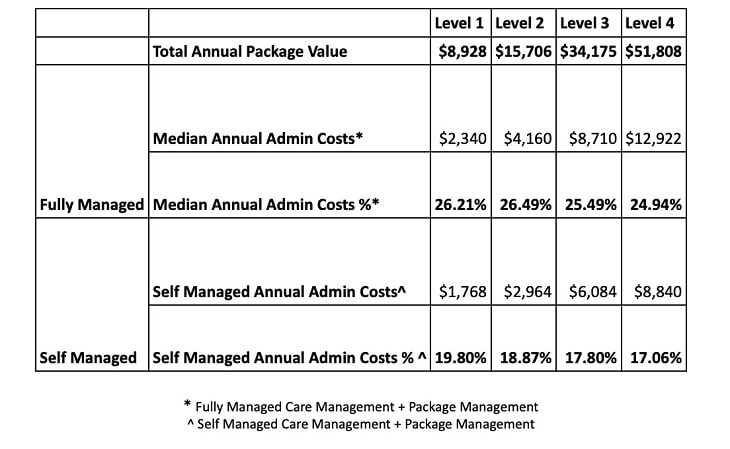

It analysed federal government data to show the price differences between provider-managed and self-managed home care.

It says older Australians are being charged an astounding one-quarter of their home care funding on “administration” and “care management”, leaving only 75 per cent for direct care and support. They are then charged significantly more per hour for services such as nursing and personal care if they have a provider-managed package, Mable claims.

Public health researcher and aged care advocate Dr Sarah Russell says extra government funding for the sector was a win for aged care providers, but not for older people.

“The government has not put in place any accountability measures to stop the rorting of the system. How is it possible that a recipient of a level 4 home care package worth $52,000 receives on average only eight hours and 45 minutes of support (per week, accepted average is 14-15 hours)?”

So what’s the solution? In essence, it’s to think about those years before you have to, which is easier said than done. It’s also about community leaders providing options that better suit healthier longer-living generations.

Australians’ average life expectancy is into the mid-80s – that’s an extra 30 years since the Age Pension was introduced in 1909.

While an ageing Australia has many economists worried, at least one group saw it as a marvellous challenge. Participants in the Longevity By Design Challenge sought to envisage life in Australia in 2050. The aim was to identify ways to prepare and adapt Australian cities to capitalise on older Australians living longer, healthier and more productive lives.

Writing for The Conversation, Rosemary Jean Kennedy, adjunct associate professor of architecture and urban design at Queensland University of Technology, and Laurie Buys, professor and director of the Healthy Ageing Initiative at the University of Queensland, say that one way to support economic and social participation is to reconsider the factors – physical, regulatory and financial – that determine how our buildings, suburbs and streets are organised.

Read: Seven trends that will better integrate ageing Australians into communities

The ‘challenge’ brought together 121 professionals (of all ages) plus older people to explore how baby boomers will change the landscape of living, learning, working and playing.

They suggested such approaches as ‘walkable neighbourhoods’ that reduce distances between homes and services and converting typical house blocks into ‘super blocks’ where multiple generations can live.

The authors wrote: “The Longevity by Design Challenge identified a range of opportunities to create a vibrant ‘longevity’ economy by including people of all ages. Small, incremental and affordable changes towards resilient and age-friendly communities can transform perceived burdens into real assets.

“Planning communities to embrace, not exclude, people over 65 has all kinds of benefits for Australia.”

There you have it. How to make it happen? That’s the next challenge.

What’s stopping/stopped you from sorting out your aged care needs? Why not share your thoughts in the comments section below?

If you enjoy our content, don’t keep it to yourself. Share our free eNews with your friends and encourage them to sign up.