Those living with a type of dementia that affects younger people can’t feel as happy as they did before developing the disease because the pleasure system in their brain has deteriorated, new research suggests.

The study, published in the journal Brain, involved 172 participants, including 87 people with the dementia type called frontotemporal dementia (FTD), and 34 with Alzheimer’s disease.

The University of Sydney’s Muireann Irish has spent seven years on the project.

Professor Irish explained that she and her team set out to answer a simple question: can people living with different types of dementia experience pleasure the same way they did when they were healthy?

They used two strategies to uncover the answer.

Firstly, they asked carers to evaluate how much their loved one experienced pleasure prior to the onset of the disease, allowing them to compare the affected person’s happiness levels pre- and post-diagnosis.

“We found that patients with frontotemporal dementia showed a marked drop from their pre-dementia [happiness] ratings to the current moment,” Professor Irish said.

“We didn’t find the same striking loss of pleasure with patients with Alzheimer’s disease, which is quite interesting in itself.”

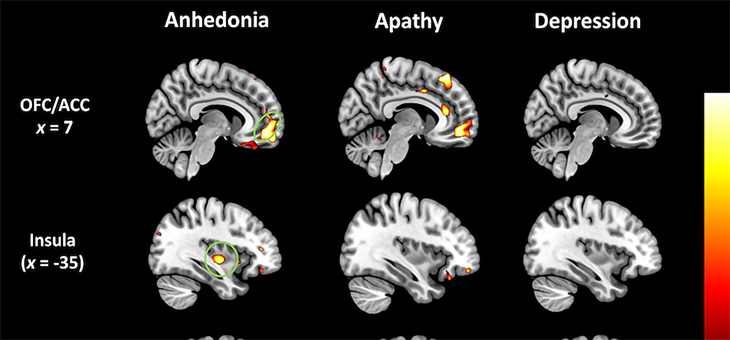

The research team then used imaging technology to conclude that the loss of joy reported in people with FTD was related to the deterioration of their brain’s pleasure system.

“We know [people with FTD] become extremely withdrawn and quite apathetic and lose interest in social engagements, in hobbies they used to pursue,” Professor Irish said.

“They end up becoming very withdrawn and isolated.

“All these signs point to perhaps there is a blunting, or a dampening of pleasure in these patients, and that’s exactly what we found in this study.”

FTD a ‘pretty nasty disease’

In FTD, the parts of the brain behind our forehead and temples become progressively damaged.

It typically affects people at a younger age than Alzheimer’s disease, with symptoms beginning in the 50s or 60s, sometimes younger.

Austin Health aged care research director Michael Woodward, who was not part of the study, described it as a “pretty nasty disease”.

It leads to noticeable changes in a person’s mood, social behaviour and judgement, and they often appear selfish, lack empathy and behave impulsively.

“Dementia is tragic at any age, but when you have these people at the prime of their lives being affected by this devastating disease of which there is no cure, that is particularly tragic,” he said.

Dr Woodward said it usually took about six months for people with other types of dementia to get a diagnosis, but FTD could take one to two years to diagnose.

He said for most people with the disease, the first signs usually involve inappropriate behaviour, such as telling crude jokes in front of young children or loudly criticising strangers within hearing distance.

People are seen by a neurologist, geriatrician or psychiatrist before they’re diagnosed, and part of this diagnosis typically involves a brain scan and blood test.

Dr Woodward said if specialists could recognise social behavioural and emotional intelligence changes earlier, it might point towards a diagnosis quicker.

“I guarantee you there are people in Australia right now who are struggling with frontotemporal dementia who are 50 or 55, but are still struggling to get a diagnosis,” he said.

“So maybe understanding what’s going on in the brain, and that’s what this paper sheds light on, could at least tweak to the possibility of the diagnosis at an earlier phase.”

Professor Irish agreed. She said loss of happiness could be a “very early indicator” for the pathological process long before doctors start to see changes in a person’s memory or cognition.

“I think we could go as far as saying this is an unrecognised symptom of frontotemporal dementia,” she said.

“Anecdotally, many people that I’ve spoken to about these findings have said, ‘my God, that’s exactly what happened with my father or my grandmother … they stopped enjoying things’.”

Future implications for FTD treatment

There is currently no cure for FTD, but Professor Irish said the study had implications for therapies.

“It helps to understand that changes in behaviour are not the result of being difficult or being oppositional. It’s being driven by the brain,” she said.

“It’s not simply that your loved one is acting deliberatively defiant, or they don’t want to join you for dinner.

“It’s more that the circuits in the brain that allow them to anticipate and respond positively to those experiences are not working properly.”

Professor Irish added that, for example, music therapy might not be as helpful for someone with FTD as it is for those with Alzheimer’s disease.

“This study is really cautioning against a one-size-fits-all model of treatment,” she said.

© 2020 Australian Broadcasting Corporation. All rights reserved.

© 2020 Australian Broadcasting Corporation. All rights reserved.

ABC Content Disclaimer