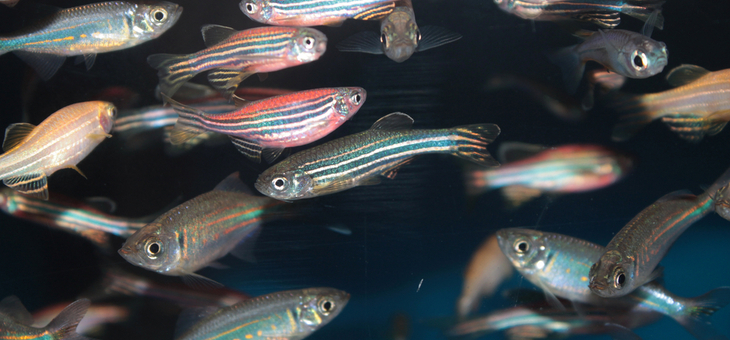

A four-centimetre torpedo-shaped tropical fish native to Southeast Asia could help save human lives.

The zebrafish has 70 per cent of its genes in common with humans, and it can completely “regenerate and repair damaged heart muscles”.

Studying this remarkable capacity, scientists from the Victor Chang Cardiac Research Institute in Sydney found the ‘genetic switch’ in zebrafish that allows this repair. It has created hope that by activating the same mechanism damaged human heart muscles could also be repaired after a cardiac arrest.

Dr Kazu Kikuchi, who led the study, says: “Our research has identified a secret switch that allows heart muscle cells to divide and multiply after the heart is injured. It kicks in when needed and turns off when the heart is fully healed. In humans, where damaged and scarred heart muscle cannot replace itself, this could be a game changer. With these tiny little fish sharing over 70 per cent of human genes, this really has the potential to save many, many lives and lead to new drug developments.”

Read more: Massive imbalance in heart attack treatment care

When turned on in zebrafish, this genetic switch allows heart muscle cells (cardiomyocytes) to multiply after a heart attack, resulting in the complete regeneration and repair of damaged heart muscles, explains genengnews.com.

The study concentrated on the protein Klf1, previously identified for its role in red blood cell development.

“Klf1 can make uninjured heart muscle cells more immature and change their metabolic wiring. This allows them to divide and make new cells. When Klf1 is not present, the zebrafish heart cannot repair itself after an injury such as a heart attack, which demonstrates its crucial role in healing.”

The crucial protein plays no role in the growth of the heart and its regenerative capacity only kicks in after a heart injury.

Read more: Nine heart health myths busted

“The team has been able to find this vitally important protein that swings into action after an event like a heart attack and supercharges the cells to heal damaged heart muscle. It’s an incredible discovery,” says Professor Bob Graham, head of the institute’s Molecular Cardiology and Biophysics Division.

“The gene may also act as a switch in human hearts. We are now hoping further research into its function may provide us with a clue to turn on regeneration in human hearts, to improve their ability to pump blood around the body.”

Prof. Graham told The Australian that humans lost the ability to turn on the regenerative protein sometime during our evolution.

“If we can understand that and find out why, we might be able to better utilise the protein to allow hearts to repair after an injury like a heart attack.”

Heart disease remains the leading cause of mortality throughout the world. Most mammals struggle to repair damaged heart tissue, though humans can replace structural cells in the liver, blood, and skin. After cardiac arrests, our hearts suffer scarring, which leads to ongoing problems and the threat of future heart attacks. The “one-year mortality rate” for heart attack patients is 26 per cent and life expectancy is lower than for many cancers. Cardiac stem cell research has failed to deliver a breakthrough, bringing renewed attention to zebrafish.

Though the zebrafish heart is simpler than ours, it is structurally similar, and its genome is fully sequenced. When a zebrafish heart is damaged, its can eventually remove scars.

Have you had heart issues? How did you cope afterwards?

Read more: The difference between a heart attack and a cardiac arrest

If you enjoy our content, don’t keep it to yourself. Share our free eNews with your friends and encourage them to sign up.