Associate Professor Leila Karimi , Chanith Wijeratne, Professor Meg Morris and Professor Tissa Wijeratne.

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues, we’re learning more about the potential long-term impact of COVID-19 on the human brain.

Globally, millions of people have contracted COVID-19 over the past few years, and some have even caught the virus two or more times. Of more than 665 million cases worldwide, nearly one in every two people with COVID-19 is at risk of developing Post-COVID-19 Neurological Syndrome (PCNS).

Recurrent infections may also increase the risk of developing PCNS, so it’s important to understand the current status of PCNS because we’ve learnt a lot about this debilitating condition since we started investigating PCNS in 2021.

“I’m at a loss”

Symptoms of PCNS mimic some of the symptoms we see after a stroke and younger adults seem to be at particular risk.

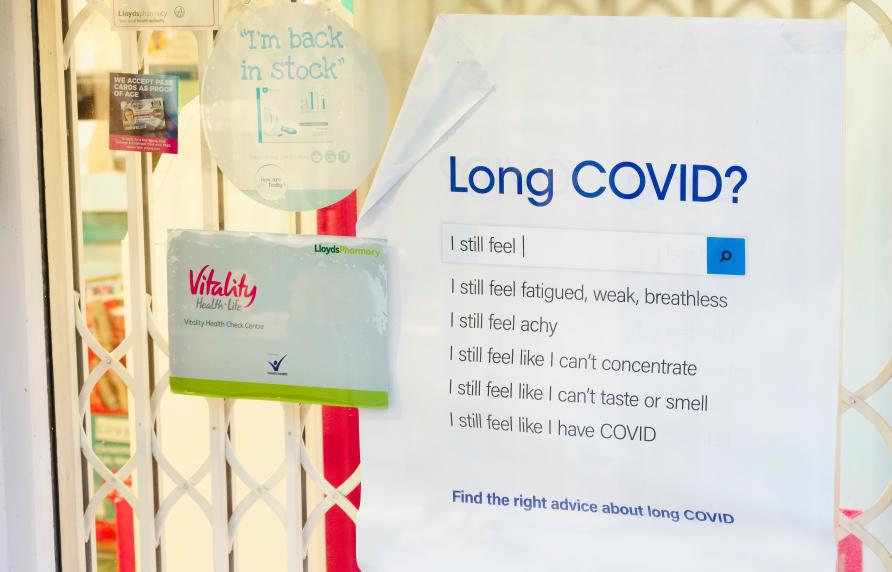

Fatigue, myalgia, arthralgia, chest pain, altered taste or smell, brain fog, headache, memory difficulties, anxiety and/or reduced mood, muscle weakness and overall inability to work have been the main symptoms noted within our cohort of COVID-19 patients to date.

PCNS, or ‘long COVID’ as it’s also known, first gained widespread recognition among social support groups before further study by the scientific and medical communities.

It’s worth noting that a link between brain health and coronavirus infections has been known since 2006, so in this context the long-term impact of COVID-19 on the brain may arguably be the expectation rather than the exception.

And for those enduring it, its impact is very real.

“I felt totally lost in the system after COVID-19. I have not been able to return to work as a healthcare worker with full capacity, even 14 months after my acute illness.

“Twenty six therapy sessions and anti-depressants did not help me at all. Persistent fatigue and brain fog has destroyed me and my young family. I have had three normal MRI brain scans, and four neurologists told me they could find nothing seriously wrong with me. I am at a loss …” (PCNS patient).

The long-term effects of COVID-19 infection are numerous and are creating unprecedented challenges for already struggling healthcare systems across the globe.

Brain health is particularly at risk.

Nearly one in two people who have reportedly recovered from acute COVID-19 cite disabling fatigue – that is, fatigue lasting more than 12 weeks – coupled with a series of attention and cognitive deficits similar to persistent post-stroke neurological symptoms.

Given the continuing proliferation of COVID-19, further research is now a matter of urgency.

A recent systematic review explored the prevalence of persistent symptoms in a general post COVID-19 population of 735,006 participants across 194 global studies.

Most of these studies were conducted in Europe or Asia and the time to follow-up range from 28 days to 387. At least 45 per cent of COVID-19 patients reported at least one unresolved symptom with a mean follow-up 126 days. Fatigue was frequently reported across both hospitalised and non-hospitalised people.

COVID-19 and brain health

The exact pathophysiology – or the functional changes that accompany a particular syndrome or disease – of PCNS and why it only appears to affect some people is not clear yet.

Persistent maladapted immune dysregulation (when the body can’t control or restrain an immune response) seems to play a key role. A simple bedside full blood count may provide clues to this when used in the calculation of the serial systemic immune inflammatory indices (SSIIi).

We have already reported on the shared pathobiology between stroke and COVID-19 at a cellular level. So, it should not be surprising to see the long-term impact on the brain with a persistent inflammatory response (potentially due to viral persistence, immune dysregulation or autoimmunity).

Another recent study found that being female, having more than five early symptoms, shortness of breath, prior psychiatric disorders and specific biomarkers (like D-dimers, CRP and lymphocyte count) were all reported as potential risk factors for long COVID, although more work needs to be done in this area.

People with PCNS often complain about ‘brain fog’ and other cognitive difficulties.

One UK study compared brain scans of 785 people and found “changes in brain structure” associated with SARS-CoV-2. The people involved in the study had undergone brain scans before the pandemic and again after contracting the virus to explore how COVID-19 infection impacted the brain.

They studied various facets of brain structure and function, including cortical thickness across multiple brain regions and found it decreased more in those who had had COVID-19 compared to those who had not.

Our team plans to conduct a prospective study of PCNS and use highly sophisticated, powerful seven T MRI brain scans (these kinds of brain scans are not routinely used in clinical settings and the resolution power is unbelievably high) as part of our collaborative research program.

PCNS and Parkinsonism

Concerningly, a few published single-case reports exist where patients with COVID-19 developed clinical Parkinsonism (stiffness, slowness and lack of movement seen in Parkinson’s disease) within two to five weeks of contracting severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2).

In one particular case, a previously healthy 58-year-old man developed a loss of smell, generalised myoclonus (muscle jerks), intermittent changes in consciousness, altered complex eye movements and Parkinsonism with vision abnormalities after a severe SARS-CoV-2 infection.

He slowly improved without any specific treatment.

At this point in time, it’s impossible for us to be certain about a cause-and-effect relationship between PCNS, Parkinsonism and related disorders. But it does tell us there needs to be more research using a well-characterised global, harmonised registry with long-term follow-up.

Preliminary evidence does suggest that personalised rehabilitation and graduated exercise training may help certain people with PCNS to keep mobile.

Activity planning, cueing and pacing of physical activities can be trialed, as well as strategies to maintain strength and balance, conserve energy and manage fatigue.

These tactics for people with PCNS can be similar in their usefulness for managing chronic fatigue syndrome and myalgic encephalitis, along with therapeutic drugs repurposed from similar conditions – although more research is needed in this area.

Collaboration, Communication and Cooperation

Primary care physicians, neurologists, physiotherapists, psychologists, nurses and other health professionals, as well as scientists, must pay close attention to this rapidly evolving condition.

Global collaborations and inter-professional cooperation are critically important given the potential impact of PCNS worldwide. Our team all plan to take part in a global PCNS registry in partnership with the University of Melbourne and other stakeholders at the time of writing.

Given that one in three people will develop some type of neurological disorder in their lifetime, an improved understanding of PCNS is urgently needed.

“This article was first published on Pursuit. Read the original article.

If you have suffered COVID-19, please consider participating in ongoing clinical research that may help both you and others. For more information you can contact us at [email protected].

Many of the basket of “long-covid” symptoms have also been linked with documented covid vaccine harms in offical datasets. Why am I not seeing research that considers the possible contribution of vaccines to “long-covid”? As that cited study said “…assessing the impact of vaccination status on Long Covid prevalence was beyond the scope of the current review. Future reviews should seek to investigate the prevalence of Long Covid across vaccination status and different variants of SARS-CoV-2.