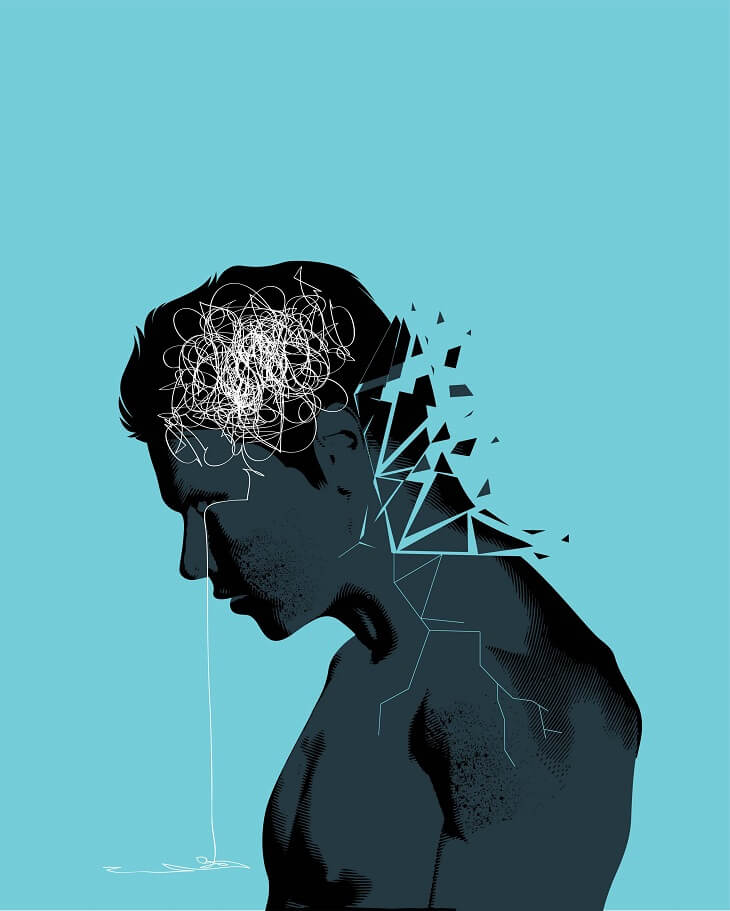

The coronavirus crisis will have lasting economic, political and social consequences, but – unsurprisingly – it’s leaving its mark on many people psychologically too.

Experts are estimating that there will be hundreds of thousands of new cases of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as a result of the pandemic.

PTSD, an anxiety disorder that’s normally associated with war veterans, can affect anyone exposed to a traumatic event. There is particular concern for frontline healthcare staff and some patients who were hospitalised with severe symptoms.

The Royal College of Psychiatrists say estimates by the NHS Strategy Unit suggest there could be 230,000 new referrals for PTSD between 2020/21 and 2022/23 in England alone.

What are the symptoms?

Dr Alison McClymont, a psychologist specialising in mental health, says: “Symptoms will focus around avoiding connecting with the memory that was traumatic, this might present itself as hyper-vigilance (a feeling of being on edge), increased irritability, panic or, in extreme cases, dissociation (a feeling of being ‘outside of your body’).

Read: Mental health support for older Aussies

“This might produce intrusive thoughts or images where the body is trying to force the brain to process the memory and place it in the long-term memory store, rather than triggering the fight or flight mechanism where the body believes it ‘is still happening’.

While GP Dr Rhianna McClymont adds: “Many people with PTSD push memories away, avoiding people and places connected to them and refusing to talk about what happened. This can make them feel emotionally numb and withdrawn. You’re likely to relive the experiences of the event through nightmares and flashbacks.

There are often physical symptoms too, she says, such as headaches, dizziness, chest pains and stomach aches. “Symptoms usually develop within a month, but sometimes can develop several months, or even years, later.”

Why is it happening as a result of the pandemic?

“A pandemic is a traumatic event,” says Dr McClymont. “It’s entirely logical and reasonable that it induces PTSD – someone’s entire sense of safety and reality has been threatened.”

Many people experienced (and are still experiencing) feeling a loss of control, social isolation and a significant financial impact, and all of these things can cause PTSD at their most extreme. If someone close to you has died as a result of COVID or you’ve been very ill and hospitalised yourself, your risk factor goes up further.

“If you have experienced a tragedy as a result of this – the trauma is compounded and it makes sense a person’s psychology would desperately attempt not to remember, or to avoid the situation happening again, so the pain is not re-experienced,” she adds.

What about frontline staff?

For many healthcare workers, the impact of the crisis has been monumental.

“Let’s be frank,” says Dr McClymont, “witnessing many people dying and being helpless due to lack of resources or support to help them, is one of the most traumatic things a person could experience.

“Feelings of helplessness in response to trauma have been shown by research to have a monumentally significant effect on whether or not PTSD will later develop. The emotional memory of being stuck and without control is one of the precursors to PTSD.”

A recent study by Oxford University found that PTSD in healthcare workers during the pandemic was often exacerbated by past trauma, too.

What help is available?

It’s important to recognise the symptoms early, says Niels Eék, psychologist and co-founder of mental wellbeing app Remente.

Read: Are mental health apps the new fix?

“I would always recommend the first steps to be to talk with a loved one or someone close about what you are feeling or experiencing.

“Secondly, speak to your GP. Your GP is trained to recognise and treat mental health too. The good news is that PTSD is treatable; the earlier the prognosis, the better the outcome,” he says.

Left untreated, PTSD can cause depression, anxiety or phobias, says Dr McClymont. “It’s not unusual for people with PTSD to misuse drugs and alcohol, and to consider self-harming, or to have suicidal feelings.”

But there are effective, specialist treatments available. “Psychological therapies are an important part of treatment for PTSD, and options include counselling and CBT,” she says. It can often be helpful to talk about experiences in a group situation – lots of charities run local PTSD support groups.

Read: EMDR: Delving into the trauma therapy used by Prince Harry

“Therapy for PTSD can include trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapy (TF-CBT), a specific form of CBT that helps treat PTSD by helping people confront traumatic memories and come to terms with the events that took place,” Dr McClymont adds.

“Another is eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR) – a newer treatment that can reduce the symptoms of PTSD by changing the negative way people think about a traumatic event.

Occasionally, medication such as antidepressants can be used for severe PTSD symptoms.

Do any of these symptoms feel familiar to you? Do you have a good support network around you? Let us know in the comments section below.

– With PA

If you enjoy our content, don’t keep it to yourself. Share our free eNews with your friends and encourage them to sign up.

Disclaimer: This article contains general information about health issues and is not advice. For health advice, consult your medical practitioner.