Jane Messer, Macquarie University

You need thalassa therapy, the woman said to me, knowing I was ever so anxious and sad about too many things. These included my mother’s months in hospital and decline from Alzheimer’s, made worse by all the stops and starts to any of us being able to visit her at the aged-care home during COVID.

I would weep in short sobs or just tears streaming, any hour of the day. There was also the fraught health of one of my children. I’d wake in the middle of the night, with a ping of fright flowering in a burst in my sternum. At the university where I worked, we were suffering endless rounds of workplace change, redundancies and the ominous morning emails from our dean and vice-chancellor. I was waking each day with a feeling of dread.

To put it simply, there was a lot going on and it all involved uncertainty, worry and rarely, hope.

“In the early morning before the day has told you what it is going to be like, take yourself into the sea. Give yourself your thalassa,” the kind woman told me.

To give yourself thalassa therapy is simple. You walk into the sea, and immerse yourself, all of your body, from head to toe. The ancient Greek word thalassa simply means the sea. The Greek sea was a she, and Thales was its primeval spirit, and like the sea, her body was strong. She spawned both fish and storm gods. In some Greco-Roman mosaics she has the sharp horns of the crab claw. She is fish-tailed, her hair is black and thick. Dolphins, sea horses, octopus and fish swim with her.

Wikimedia Commons

It was to McIver’s pool that I began to go for my morning thalassa. I wanted the calm waters of the pool, not the turbulent exuberance of the surf. I would arrive long after dawn on a weekday, but still early enough that the sun was slanting brightly along the pool’s moving, shimmery surface. A friend came with me, a woman who has swum there countless times. She is sun-browned, creviced and wrinkled, lean and strong. She has walked up and down the steep steps to the sea pool many times. She’d slide into the water ahead of me, then lap easily, for she’s long been an ocean swimmer.

I didn’t lap, not to begin with. I’d dip myself down, my toes feeling out the serrations of rock and shell, the silk of the weeds. I’d feel the sea water loosen and slide through my hair. I’d feel the change from air to water, from warm to cool, from busyness to simply being, under the sea. Submerged, I’d open my eyes to look up through the water to the sky, my breath bubbling to the surface in pockets of light. The sea pool made my body my friend again. I felt then that it had always been thus, for a few moments, lithe and buoyant, and almost joyful.

Over on the undersea rock face, live purple and black-spined sea anemones, barnacles, cockles, crabs, and sea urchins. Sometimes there have been octopus. Small fish dart about, Maori wrasse and Old Wives, fish that are plain grey and short-finned, or colourfully striped with fins that undulate. From the northern rock’s overhang, water falls in precise droplets to the tiny rock pools below, each droplet arriving with a startlingly bright miniature splash.

Shutterstock

I would take a deep breath, dive, and swim across the rocky floor, then swivel with a twirl and lie on my back gazing, not breathing, letting the sea do its therapy.

Sometimes, if it was early, there was just myself and my friend, or another swimmer or two lapping, or a woman simply floating. There is a pool net for sweeping up any bluebottles that have swept in over seawall. One day my friend and I removed six. A woman in a floppy red hat was treading water slowly, gazing at the water, the mosses, at us at our task, at nothing in particular. On a small square of concrete on the ocean side of the pool, a woman moved gracefully in a slow tai chi dance, her face towards the sun.

A dimpled Rubenesque woman stepped down the stairs holding her loose bare breasts in her hands, then let go when she reached the water. A young woman stepped out, water streaming as she shook her long hair. She climbed the stairs and sat above us, crossed-legged, facing the early morning sun to dry, like a cormorant.

Wikimedia Commons

Sometimes the women on the rocky points remind me of basking seals, round and gleaming with oil or water, or of seabirds drying their wings before the next dive. I have seen so many bodies here: wrinkle bummed, wobbly bummed, long breasted, with shell-white skin, and skin that is mottled from a lifetime of use.

You can tell who the ocean swimmers are if they’re a bit older because they have lean arses and strong shoulders and invariably wear Speedos. When I shower, peeling off my swimmers, rinsing my hair and skin in the cold water, then walking to one of the benches where my clothes lie in a tumble, I feel a little embarrassed that I have almost no pubic hair now, whereas my friend, who is much older than me, still has hers. Is she still, after all these years, naturally brown? I could dress in the privacy of one of the change rooms, but that would be missing the point. I seem to have become like my late godmother. I saw her sparse white hairs once when she’d accidentally left a button undone on her ‘housedress’. I now remind myself of her, or of an old dog’s grey snout.

On sunny weekends, groups of women in twos and threes track across the rock platforms looking for an untaken space to sun bake. Out come the towels, the cool drinks and fruit, the sunblock, books and hats. One time I watched a black-haired woman reveal herself as a toned athlete in an apple-green G-string. Then she folded her hijab away into her beach bag and lay back.

At the pool, a woman can be as (non)attractive as she likes, and nothing bad will happen. No military general, media commentator, or politician will warn her that she’s being provocative. She can dry herself off with long leisurely strokes of her towel, or give herself a brisk rub-down. She will not be followed, touched, slurred or victim-blamed. She can stretch her arms out to the sun and laugh out loud, or curl up with a book on the grass in shorts and singlet. No-one will film her unawares.

For those who swim at the women’s pool, how fortunate we are to have this safe place, open almost every day of the year from sunrise to sunset. Though even here, there are the histories of violence toward and dispossession of the Eora coastal women. Let us neither forget, nor not know.

At the pool there are no mirrors

The Women’s Baths welcomes us to its shelves of stone and grass for drying off, to doze, to talk, to preen, to gaze into the aqua green, ivory and midnight blue pool, to the rocks and outcrops either side, and the Pacific Ocean beyond.

I wish I could bring my mother here. The minutes of joy and refreshment that I experience now in my morning swims, I wish my mother could have too. Not that she likes cold water, or wind coming off the ocean. She was always confident in her body, walking about unabashed from bathroom to bedroom, stopping on the way to say something to her cringing daughter.

As a girl unwillingly becoming a young woman, I was horrified by the ever-so-slight sag of her stomach and gnarly brown nipples and the unapologetic lack of shame. The pool is the great leveller, welcoming the agile and the infirm, the exceptional and the ordinary. Much of the time I now gladly inhabit my body, that has born children, braved surgeries, and most grievously, lost its beautiful, saucy oestrogen after menopause. I’m well aware that all-in-all, my body has done me remarkably well so far.

At the pool there are no mirrors to see oneself in, other than the dappled water. There is much to feel about oneself though – your own salty skin and dripping hair, the ancient sandstone beneath your feet, the frisky embrace of the tidal sea water and ocean breezes. Swimming in the water I feel myself whole, from head to toe.

Rubbing my hair dry one time, feeling the sun-warmed towel on my cold scalp, I remembered a terrible moment a few months ago, when my mother was still in the hospital. She asked me, “Where is my head?”

Your head? Your head is here, I said, touching her hair gently, expecting that once she felt the contact, she’d know it again. “But, where is it?” she insisted.

She has always been a conceptual person, interested in systems and relations.

It’s at the top of your body, here where it always is, at the end of your neck, I said. I felt her confusion like a small, contained explosion within me. Another part of her mind had disassembled, fallen off like a loose rock might.

Only when I crouched down in front of her, held her hands to anchor us both, and looked at her did she begin to reorient herself. You’re looking at me from your head, Mum, I said.

“That’s right,” she said, nodding. Everything was back in place again.

There are times in your life when you need help and nurture, and to feel safe. And so, I take my morning thalassa therapy, arriving before the day has told me what it is going to be like.

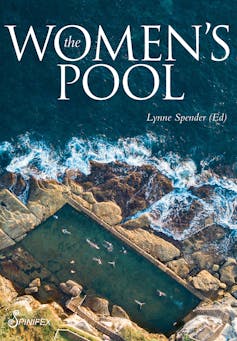

This is an extract from The Women’s Pool edited by Lynne Spender (Spinifex Press).![]()

Jane Messer, Honorary Associate Professor in Creative Writing and Literature, Macquarie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.

Have you tried thalassa therapy? Why not share your thoughts in the comments section below?

If you enjoy our content, don’t keep it to yourself. Share our free eNews with your friends and encourage them to sign up.