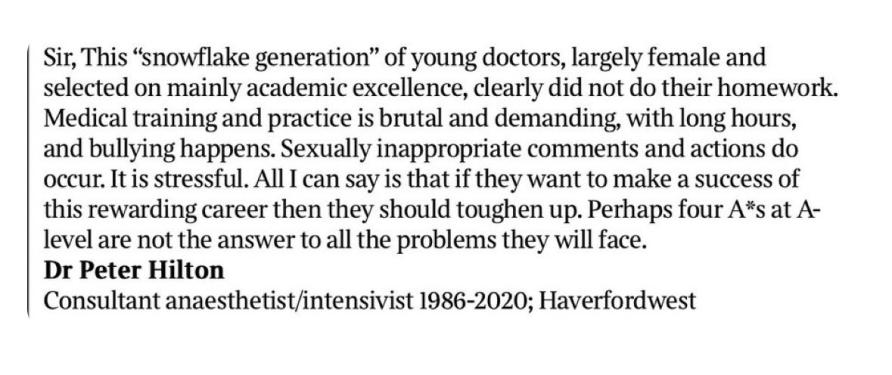

Over the month or so, there has been widespread condemnation of a letter to the editor penned by a retired British anaesthetist and published in a UK newspaper.

In his letter, Dr Peter Hilton described female doctors as a “snowflake generation” who need to “toughen up” in response to new research showing that 30 per cent of female surgeons had been sexually assaulted by their male colleagues while at work.

While his comments sparked outrage, he went on to defend his stance. “You will meet people who are bullies, you will meet people who are misogynistic and do inappropriate things but deal with it. I’ve sent the letter to colleagues I worked with and they agree wholeheartedly.”

Sadly, he is correct about the fact that many of his colleagues agree. He is incorrect in saying female doctors should just “deal with it”.

But opinions like Peter Hilton’s are not isolated. They are widespread in our public hospitals.

I’ve seen it, heard it and lived it.

Misogyny in medicine in 2023

While female medical students at universities in Australia have outnumbered males since the mid-1980s, there remains significant underrepresentation of women in leadership across all medical and academic fields.

Especially in senior prestigious roles.

In my specialty of endocrinology, of the 11 teaching hospitals with endocrine departments in Victoria, only two are led by a female.

This is despite 78 per cent of endocrinology trainees being female.

When raised, most men are shocked and oblivious to that dominance – a reflection of their unconscious bias and privilege.

But repairing broken systems becomes impossible when leaders view misogyny as a shocking anomaly instead of acknowledging it as an underlying structure.

Hospitals are hierarchical institutions built by men for men.

Whether it’s the name of a lecture theatre, a hospital wing or the portraits adorning the walls – the patriarchal culture is unmistakable. There are few spaces where women are represented and visible.

Outright discrimination is common, ranging from unconscious bias, repeated microaggressions, to harassment, bullying or sexual assault. Under-reporting of such behaviour in Australian medicine is endemic.

The small microaggressions faced by female doctors occur daily; “are you a nurse?” or “you’re so bossy” are common, being interrupted when speaking, or having ideas and suggestions ignored in meetings but then finding those same ideas appropriated by a male doctor who then receives credit.

Cumulatively, microaggressions like these have been clearly shown to negatively impact the physical and mental health of recipients.

Men hold most of the senior leadership roles within public hospitals and, as such, control performance reviews, references and the future careers of medical staff they supervise.

This power imbalance in hospital structures perpetuates inequity, with junior staff often gaslit or feeling unable to report inappropriate behaviour for fear of reprisal.

Leaders, once appointed, often remain in their roles until they retire. Even when complaints about misconduct are raised, they can be ignored for years with little prospect of effecting change.

Hospital leadership structures need a radical review to enable psychological safety to speak up and ultimately, to nurture innovations most effectively in patient care.

Female doctors are quitting

Research has found that female doctors do more for our patients for less recognition. Salaries of female doctors are 12 to 25 per cent lower than males across all specialties, even after accounting for hours worked.

There are less resources to support women – whether it’s financial resources, support staff or disparities in mentoring and sponsorship.

On top of the gender pay gap is a workload gap. Female doctors undertake more mentoring of junior medical staff, accept more committee service, are more likely to answer patient queries and more accurately document in medical records.

All highly important but invisible work.

Outside of the hospital, inequity doesn’t end. High achieving female physician scientists spend 8.5 hours more per week than their male counterparts on domestic activities like caring for children or family.

This disparity was magnified by the COVID-19 pandemic. During the pandemic, male medical researchers published more studies than women compared to pre-pandemic levels – which suggests that women are at far greater risk of falling behind their male colleagues during and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic.

Not surprisingly, the constant inequity and battles for recognition negatively impact physical and mental wellbeing.

When women don’t feel heard, they disengage, don’t turn up or they leave. Burnout, depression, inability to find professional fulfilment and realise career goals and amplified imposter syndrome are just some of the consequences.

Harm is magnified for women who are part of other underrepresented groups like women of colour. Research shows that across every career stage, female doctors are leaving teaching hospitals, or are planning to withdraw, at a higher rate than male doctors.

All of this is happening at your local hospital.

Female doctors provide better patient care

Despite these workplace challenges, patients of female surgeons and physicians have better outcomes, unrelated to case complexity.

Doctors from diverse socio-educational backgrounds better serve the community, and there is clear evidence that patients are not only less likely to die, but have fewer surgical complications, hospital readmissions and even better control of their diabetes with female doctors.

The relative risk reduction of 4 per cent seen by patients of female doctors compared to patients of male doctors is equivalent to the reduction in all-cause mortality seen over the last 10 years because of advances in medicine.

Many female doctors practice medicine differently to male doctors and research supports this.

They are more likely to provide preventative care, use patient-centred communication, provide more psychosocial counselling, take more time per patient, may be more deliberate in their approach to solving complex problems, are more likely to adhere to clinical guidelines, and spend more time documenting in medical records.

Who would you prefer to have treating you next time you arrive in the emergency department?

The inability to retain female doctors was already an issue prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, but staffing shortages have now reached crisis point and will only worsen.

If drastic changes don’t occur to support and retain female doctors, we will face a hospital staffing crisis where critical health operations cannot be sustained.

Action is needed now to protect our community

Established in 2005 to encourage and recognise commitment to advancing the careers of women in science, technology, engineering, mathematics and medicine (STEMM), universities across the world have committed to the Athena SWAN Charter.

This is a framework designed to support and transform gender equality within higher education and research.

Nothing like this exists in our public hospitals or healthcare organisations.

There needs to be a commitment and mandate from government, unions and hospital boards to urgently address misogyny in medicine and embed change in governance and accountability structures.

Hospital leaders need to:

- Prioritise and appropriately resource gender equity, diversity and inclusion work

- Undertake transparent, rigorous self-assessment to analyse existing culture and barriers to gender equity

- Develop proactive plans to reduce identified barriers, increase the safety of all staff and enable system-wide cultural change. Some examples include the American Society of Clinical Oncology’s practical steps for cultural change or Ruchika Tulshyan’s ADAPT framework.

There is no reason why hospitals and healthcare organisations cannot commit to the Athena SWAN Charter or other similar frameworks like the National Academies of Medicine recommendations to address misogyny in medicine.

We have enough evidence. We already know enough to act.

Public hospitals use public funds to best serve the community. We can’t hope to effectively improve the health of the wider community if we can’t ensure that female staff in our healthcare and academic institutions are safe, healthy and well.

Would you prefer a female or male doctor? Does it matter to you? Why not share your opinion in the comments section below?

Also read: GP fees on the rise again, but relief is at hand

Sorry to all those I offend but I agree totally with Dr Hilton and his comrades in arms. In his profession it’s life and death, if you’re doing something stupid you should be called out for it, they haven’t got timed to sit you down for five minutes and explain what you should be doing and how you shouldn’t be doing it. So as he rightly put it, toughen up you’re not in kindergarten now, this is the real world. This PC rubbish of not offending anybody has gone way too far.

And not just in the Medical Profession, this applies to all walks of life. This nonsense of pleasing staff, them starting and finishing work when it pleases them is a load of malarkey. Paid maternity leave etc , I honestly don’t know how anybody can keep a business going these days. Similar to user pays, you look after your own life, you apply for a job, you get the job, you do what’s expected of you and you go home. You don’t make demands, if you don’t like the work place as it is, it’s simple, resign. After all your employer is the person indirectly paying your bills and putting a roof over your head, so show some respect and gratitude. Remember you’re the one who applied for the job and was hired, they didn’t come knocking on your door specifically did they. So whether it’s the Medical Profession, Chef’s in hospitality or general office work, toughen up, lose the nambi pambi attitude, both male and female. The only reason people get upset and abuse staff verbally, is because of your attitude and in most cases your stupidity. JACKA.

Words fail me, and your reply just reinforces what the writer of the article says. What are male doctors so afraid of, that females will show them up?

When I was at university I read a paper by an anthropologist who was studying the Caste system in India. He lived amongst the Dalit (untouchables) but would also discuss the caste system with Brahmins who belong to a higher caste. One day a Dalit said to him “You have been talking to Brahmins”. In other words the system, any system, looks fine when you’re the one on top but talk to the ones on the bottom and you’ll get a completely different view. Stop listening to the Brahmins and talk to the Dalits. Your world will change.