When Bruce Willis announced his retirement from acting in March, it not only sent shockwaves through Hollywood, but it also brought into sharp public focus the brain condition known as aphasia.

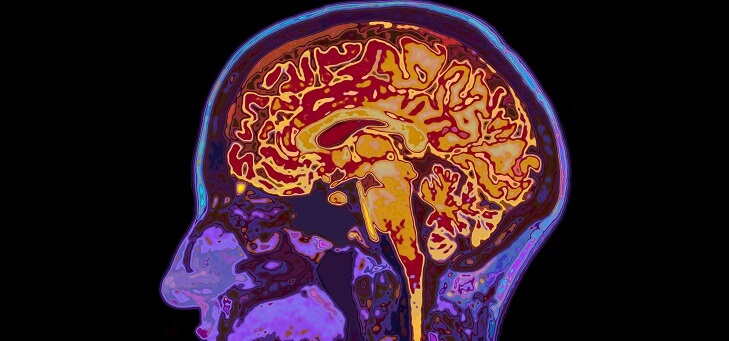

Technically a spectrum of disorders, aphasia is caused by damage in a specific area of the brain that controls language expression and comprehension. As a result, it can affect your ability to find the right word, or cause you to produce sentences with words out of order.

On that spectrum is PPA – primary progressive aphasia – a type of early onset dementia that occurs most often in people between the ages of 50 and 70. There are actually three subtypes of PPA, each with distinct patterns of brain atrophy or shrinkage, brain pathologies and prognoses.

Read: What is aphasia, the condition Bruce Willis lives with?

Thanks to some ingenuity shown by researchers and clinicians at the University of Sydney, there may be some good news in detecting this disorder. At the university’s Brain and Mind Centre, a new, online, clinician-administered tool greatly enhances the likelihood of earlier PPA detection.

Results from data derived from the tool’s use indicate a success rate of 70 to 80 per cent in determining which of the three subtypes of PPA a patient has.

The subtypes are:

- logopenic – characterised by difficulty speaking and finding the right words

- non-fluent – difficulty articulating words

- semantic – characterised by a loss or lessening of comprehension.

In each of the variants, a different region of the brain is affected.

Read: Dementia risk affected by postcode and background

Identifying which subtype of PPA a patient suffers from may help clinicians map out a treatment. At present, there is no known cure for PPA, but researchers – also from the University of Sydney – are investigating the underlying pathological causes of these diseases, which could lead to novel pharmacological interventions.

What is known is that PPA is caused by an abnormal build-up of proteins in the brain, particularly in the areas that control language, resulting in a slow, progressive loss of brain cells.

Once PPA takes hold, cognitive and functional abilities deteriorate over time. This eventually results in death, usually within seven to 12 years after diagnosis.

Because it generally presents before the age of 65, PPA can have a significant impact on family, as well as a sufferer’s work and social life.

Where speech has been affected, treatments such as speech therapy can alleviate symptoms and improve quality of life in the early stages.

Read: Everyday behaviours that could be signs of dementia

Interestingly, there have been examples of apparently enhanced function in parts of the brain as a result of PPA. In one such case, Canadian artist Anne Adams created a painting that is a bar-by-bar representation of Maurice Ravel’s iconic orchestral piece Boléro.

After Ms Adams had completed the piece in 1994, it was discovered that she was suffering from PPA, and had likely been for some time. Brain scans revealed that regions involved in integrating information from different senses were unusually well developed, and neurologists believe that these areas of Ms Adams’ brain may have sprouted new neural connections as her language centres began to deteriorate.

As wonderful as that sounds, PPA later robbed Ms Adams of her speech, and eventually took her life, so the University of Sydney’s new early detection calculation tool is a welcome development.

Do you know someone who has been diagnosed with PPA or another form of early onset dementia? How has it affected them? Why not share your thoughts in the comments section below?

If you enjoy our content, don’t keep it to yourself. Share our free eNews with your friends and encourage them to sign up.

My husband had Logopenic PPA and we noticed 10 years ago he was starting to have difficulty pronouncing words. He was not diagnosed until early 2016, as his doctor the previous year and his neurologist didn’t think anything was wrong. I had to change his doctor and neurologist to get the diagnosis. He had speech therapy which certainly helped until he was put into an aged care facility in 2019. He had lost his ability by then to speak properly and had also lost his ability to shower and he was becoming incontinent. He lost his ability to speak and move in 2020 and he died in Feb this year when he was 77.