Mary was 55 when she started having on and off tummy pains, and noticed she needed to go more often for a poo.

Her GP referred her to the local hospital for a colonoscopy, but eight months later she was still waiting when she was rushed to emergency with more severe pains.

Two days later she’d had surgery, where they found a bowel cancer that had already spread to other parts of her body. She is currently having chemotherapy.

Bowel cancer remains one of our most deadly cancers in Australia – however it is also one of our most manageable, if caught early.

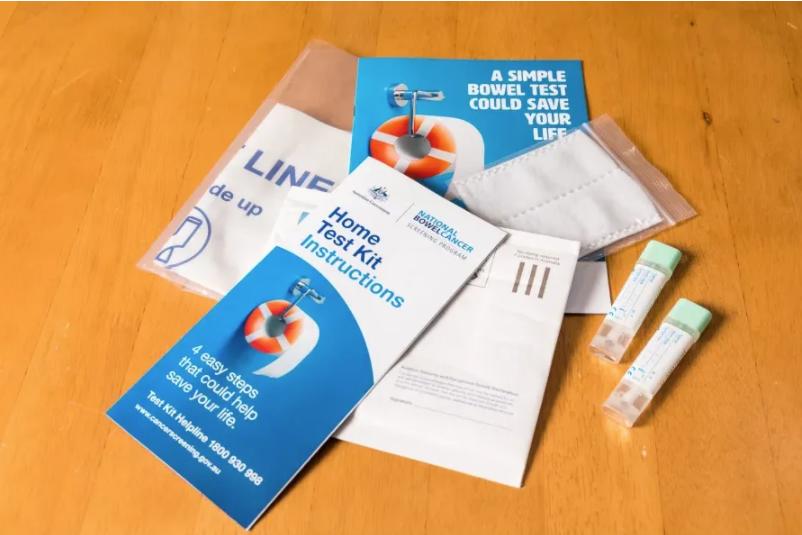

The National Bowel Cancer Screening Program sends an at-home poo test kit (the faecal occult blood test, or FOBT) to individuals over 50, to test for traces of blood – a sign of colorectal (bowel) cancer. When a positive test comes back, your GP is likely to order a colonoscopy to investigate.

The majority of bowel cancers in Australia are diagnosed when a person develops symptoms, such as diarrhoea or abdominal pain. Most of the time though, people with these symptoms do not have bowel cancer but they still require investigation to rule it out.

The demand for colonoscopies is increasing. Between 2005 to 2015 there was a 51 per cent increase in those funded under Medicare alone.

Some of this increase is due to implementation of bowel cancer screening but most colonoscopies are for people with bowel cancer symptoms. With increased demand comes longer waiting times.

The current median waiting time in the public system after a positive FOBT through the National Bowel Cancer Screening Program is 84 days. Many people with bowel cancer symptoms wait longer than this.

The colorectal cancer Optimal Cancer Care Pathway – a nationally endorsed program that aims to standardise care at critical points along the cancer care pathway – recommends a colonoscopy within four weeks of symptoms presenting.

The challenge for public hospitals is how to decide who needs a colonoscopy most urgently.

The Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care recommended that all states and territories adopt triaging systems to prioritise colonoscopies for individuals most at risk of bowel cancer, and yet, variation still exists.

In 2018, Cancer Council Australia and the Victorian Department of Health and Human Services developed triage guidelines for colonoscopy, aiming to place those who were most likely to have cancer on the urgent category, so-called Category 1 colonoscopies, based on their symptoms and results of an FOBT or common blood tests.

Published in the Internal Medicine Journal, we studied the performance of these triage guidelines for colonoscopy using de-identified data from the endoscopy services at Western Health.

We wanted to understand which of these triaging guidelines would be most effective at selecting patients with cancer for Category 1, and who could safely wait longer because they were very unlikely to have cancer.

Comparing the guidelines

The Victorian guidelines were associated with the highest detection rate (91.4 per cent of cancers would be diagnosed on the Category 1, urgent, colonoscopy list).

From an efficiency perspective, we are interested in how many urgent colonoscopies need to be done to diagnose a bowel cancer. The conversion rate for the Victorian guidelines was 5.4 per cent, that is about one in 20 urgent colonoscopies will diagnose a cancer.

The Cancer Council Australia guidelines did not perform as well, mainly because they were developed with a more limited focus of indications for colonoscopy, (symptomatic presentations) than the Victorian ones, which also considered family history of bowel cancer.

We showed that systematically applying the Victorian guidelines could reduce the proportion of urgent colonoscopies by 10 per cent without reducing conversion or detection rates.

Colonoscopy guidelines that account for age, symptoms, FOBT in certain symptomatic patients, and markers of anaemia, could improve the triage process. However, there are implementation challenges with this approach.

Referral letters often lack the detail required to apply the triage criteria, particularly about symptom duration and abnormal test results. Hospitals and GPs would need to work together to use standardised referral letters that capture all the necessary information.

It is only recently that international guidelines have suggested using FOBT in people with symptoms, and not just as a screening test for asymptomatic populations. We showed that 6 per cent of symptomatic patients would need a FOBT done to determine the urgency of their colonoscopy.

The triage guidelines are moderately complex to apply systematically, so the Victorian government provided support to the University of Melbourne to develop an online triage calculator for use by endoscopy units.

This tool enables simple entry of referral information and an automated calculation of the urgency of a colonoscopy based on the Victorian triage guidelines.

In this way, patients like Mary who need their colonoscopy most urgently can be better identified and have their bowel cancer diagnosed and treated more quickly.

Banner: Getty Images

This article was first published on Pursuit. Read the original article.

Do you participate in the national bowel cancer screening program? Have you had issues with follow-up appointments if an irregularity was discovered?

If you enjoy our content, don’t keep it to yourself. Share our free eNews with your friends and encourage them to sign up.