Jennifer King, University of Sydney

As a urogynaecologist I care exclusively for women with pelvic floor problems. These are the women with leaking bladders and weak supporting tissues allowing the vaginal walls to bulge outside.

Pelvic organ prolapse can be distressing or embarrassing and interfere with everyday activities. But it’s also common. For many women treatment is simple, effective and doesn’t involve surgery.

What is pelvic organ prolapse?

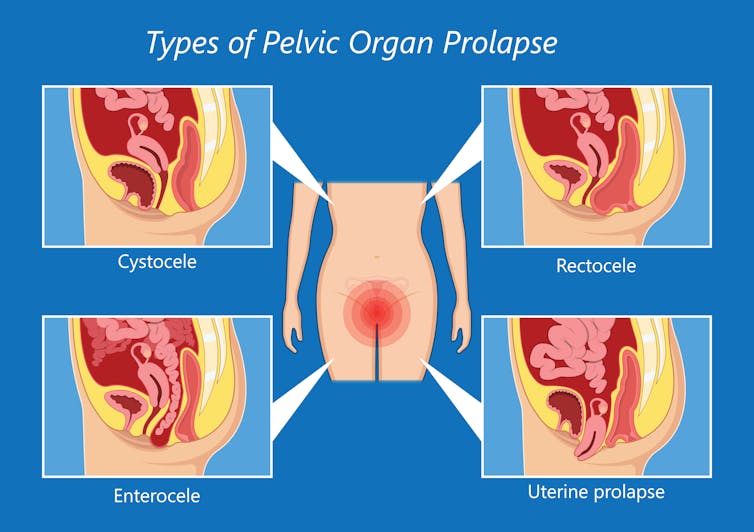

Pelvic organ prolapse occurs when the supporting muscles and ligaments holding up the vagina are weakened, allowing the vaginal tissues to sag or stretch. The pelvic organs behind the vaginal walls – such as the bladder, bowel and uterus – can then drop out of position.

One or more organ may be involved. But other than being out of position, there is not necessarily any problem with how these organs function.

Prolapse is usually described according to which organ has dropped, for example “bladder prolapse” (cystocele). Severity is graded according to extent the vaginal wall has descended from its previous position.

What does it feel like?

Most women don’t know an organ or organs have prolapsed until they notice a protrusion from the vaginal opening. They may feel a soft lump bulging in the vagina when they’re washing.

Many simply feel aware “something is coming down”.

Other women may notice they can’t trust their bladder not to leak when they’re jumping on a trampoline or running at the gym. Or perhaps they find it harder to keep a tampon in position than it was before children.

How common is it?

Prolapse is very common and its likelihood increases with age. Based on routine vaginal examination (for example, for cervical screening), easily 50 per cent of women in developed countries will be classified as having prolapse. Most of these will have no symptoms at all.

When defined by symptoms such as a vaginal bulge or difficulty passing urine, around 5 per cent will have specific symptoms.

What causes pelvic organ prolapse?

Pregnancy and vaginal birth generally cause physical changes, such as relaxation of the vaginal tissues. For most women these are minor, but for some, prolapse can seriously impact quality of life.

After pregnancy some women may find they need to adjust physical activities – particularly high impact exercise or repetitive heavy lifting – as this can make prolapse symptoms more noticeable.

Women who give birth via caesarean section are less likely to experience prolapse and incontinence. However as caesareans have their own risk of serious complications, they can’t be recommended purely to avoid pelvic floor issues.

After vaginal delivery, ageing is the second-most common cause of prolapse. This is because the strength of the pelvic floor deteriorates as we age and especially after menopause.

Excessive weight lifting and high-impact exercise can also weaken these muscles.

Chronic lung problems, diabetes, high cholesterol, constipation and obesity further increase the severity of prolapse and incontinence.

Some women also have genetically poorer quality connective tissues, making them more at risk.

How is it treated?

Severe prolapse, which persistently extends through the vagina and causes significant discomfort, is often managed with surgery.

But it is not always required. In developed countries, only 6-18 per cent of those diagnosed with pelvic prolapse will have surgery.

For milder cases, a clinician will usually recommend pelvic floor therapy.

Structured pelvic floor muscle exercises (generally working with a therapist over time) are effective as an initial treatment when prolapse has occurred. Pelvic floor training during late pregnancy can also be used to treat and prevent further prolapse or urinary incontinence.

Interestingly, general body strength and fitness does not translate into strong pelvic floor muscles – only specific exercises do this. But keeping your weight under control and managing other health conditions can help reduce symptoms.

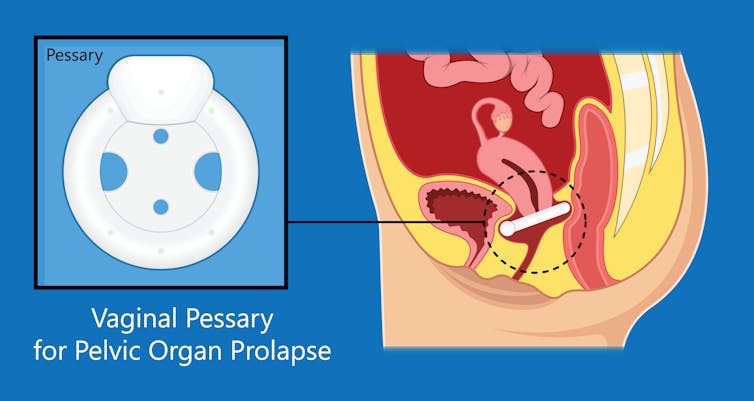

Intravaginal support devices, called pessaries, can also substantially reduce symptoms. These are usually silicone rings or discs to help support the vaginal walls. They can be fitted by doctors, nurses or physiotherapists and can often be managed by women themselves.

Prolapse can also cause mental health distress. Some women may find their body image suffers, and they may experience anxiety or depression which needs specific management.

What does surgery involve?

In severe cases, a clinician might recommend surgery if conservative management (such as pelvic floor muscle training) has been ineffective.

Surgery can also be necessary in those uncommon cases where the prolapse is affecting kidney or bowel function. In these situations surgery can restore quality of life.

Surgery for prolapse can be performed through the abdomen (usually keyhole approach) or vaginally. For most women, mesh is not required and the surgery involves reshaping and reattaching the stretched tissues to strong ligaments.

Unfortunately this is not always successful, particularly when the tissues are very weak. Approximately 25 per cent of women will need further surgery.

In 2017, the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration withdrew their approval for vaginal mesh products for prolapse, after safety concerns. There has since been a marked reduction in surgery for prolapse and urinary incontinence.

However we have not seen a corresponding increase in non-surgical treatments, so we can only assume many women are simply not seeking treatment at all.

We do need to continue working towards better and safer products to improve the durability of our pelvic floor repairs. But in the meantime we must also continue to provide individualised care for every affected woman.

For many, maintaining pelvic floor strength and a healthy lifestyle will be enough to return to and enjoy their normal activities. The first step is to talk to your GP, who can explain what options will work best for you.

Jennifer King, Senior Clinical Lecturer in Urogynaecology, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.

Is this a problem you’ve experienced? Did you need surgery? Let us know in the comments section below.

Also read: Hidden costs of breast cancer revealed

I had a rectocele operation for a prolapse in 2018. My prolapse has recurred and I’m seeing my gynaecologist on the 3rd of November.