Right now, most Australians are feeling the cold, whether you live in wet Melbourne, blustery Tasmania or central Queensland, with its desert-chilled overnights.

But each and every winter, the issue of our country’s cold housing gets national attention. Not only is living in a cold home unpleasant and uncomfortable, it also has the potential to impact our health.

At the outset it’s important to get the science of the health effects of cold housing right.

To do that, we need to look at our emerging understanding of the effects of living in a cold house – particularly on our mental health.

What exactly is cold housing?

This is a difficult question to answer.

In climates that have a cold season, 18°C is the usual threshold above which the indoor temperature of a house is considered protective of our health.

This temperature is based on a 1987 World Health Organization (WHO) report that recommended indoor temperatures are maintained at 18°C, or 20 to 21°C in rooms lived in by the elderly.

Curiously, the evidential basis for these guidelines can no longer be traced; nonetheless, the 18°C threshold has since been widely adopted around the world.

While the WHO temperature threshold offers a good guide, the negative health effects of low indoor temperatures are not triggered for everyone once this threshold is breached.

This is because different people have different thresholds and so have different health impacts.

For example, some people, including those with health conditions like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), may need a higher threshold (or temperature) to remain as healthy as possible.

For this reason, many studies that focus on measuring prevalence of the 18°C threshold are arguably less of a priority than studies that help increase our understanding of the specific ways health problems can occur.

On top of this, converting a threshold into an objective measure of cold housing exposure is not simple.

Indoor temperature is not fixed – it will vary by climate zone, time of year and even across a 24-hour period.

So, there are currently no standards in measurement.

In order to establish the health consequences of exposure to cold, our team has used a single definition to guide our research. That definition is “houses with an average temperature in the living spaces (lounge, kitchen, bedrooms) below 18°C when in use by occupants during the six inter-equinox winter months”.

While this has helped provide our research with parameters, it’s important to acknowledge that more needs to be done to define the specific nature of cold indoor exposure in relation to health.

So, how much cold housing are Australians exposed to?

Estimates of people exposed to cold homes in Australia vary from less than two per cent to an alarming 80 of 100 homes. These estimates vary so widely because (again) there is no standard approach to measurement.

The low estimates (those less than two per cent) are based on questions in surveys about people’s capacity to heat their homes, but these can be very subjective – answers may vary because of how the question is asked or differ between occupants of the same house.

The higher estimates (those at around 80 per cent) are based on the average temperature recorded by the study during waking hours (somewhere between 6am and 11pm).

But again, these measures are fallible.

They are based on assumptions about occupancy and don’t take into account whether occupants are in a particular room at the time the measurements were taken.

It would only take a small change in usual occupancy patterns – things like going into the office unexpectedly, turning the heater on at 7.30am and off at 9.30am, or heating a room other than the one being measured – to bring those average temperature estimates down to below 18°C.

All of these factors challenge the usefulness of the temperature measurements we currently rely on. The truth lies probably somewhere between these two extremes.

In New Zealand, which has a cooler climate than Australia, a third of 6,700 homes were found to be less than 18°C during the day in winter when measured directly at the time when occupants were being interviewed.

Here in Victoria, in-home monitoring found daily variations in temperature; some homes are cold for some of the time (for example, in the mornings and overnight) but also warm for some of the time (late afternoon and early evenings).

The reality is that cold housing is more likely to be a health concern for people who either cannot afford to warm their home, don’t have heating or have a house that is in poor condition. That is, homes that are persistently cold.

It’s your mental health at risk in a cold home

Recent research has found a strong link between exposure to colder indoor temperatures and risk factors for cardiovascular disease with blood pressure increasing as room temperatures decrease.

Based on reviews of evidence, the WHO has also identified that cold housing can increase people’s risk of cardiovascular and respiratory morbidity and mortality.

But our recent research suggests that by far the biggest negative health impact is on the mental health of a person living in a cold home. This is at a population level which means we’re looking at the effects on the entire population rather than just individuals.

Our study estimates that around 60 per cent of Australia’s burden of disease from indoor cold is the result of negative effects on mental health and wellbeing (with some uncertainty, of course). If we compare this to cardiovascular morbidity at 10 per cent and respiratory morbidity at 30 per cent, this figure is incredibly high.

Then if we also look at the effects of energy poverty on health – we have estimated this using longitudinal data for Australia that a person’s mental health declines significantly when they can’t afford to warm their homes or they cannot keep a room in their home warm – their odds of reporting depression or anxiety increase by 49 per cent.

So, why do you need to know this?

Well, because cold housing isn’t currently considered as a risk factor for poor mental health. And our findings go some way to explaining the socio-economic disparities for mental health in Australia.

In fact, we have estimated that improving cold housing would lead to six times more health gain for low socio-economic groups compared to high socio-economic groups. And this would help to meet the gold standard for a public health intervention that improves health and reduces health inequalities.

This is a systemic problem with our housing

It is true that, compared to housing in colder climates, our homes lack things like insulation and glazing that help our indoor temperatures remain stable and warm. But the reasons for higher rates of excess winter mortality in Australia (compared to countries with colder climates) goes beyond the insulation and glazing.

In Australia, the high cost of housing and lack of protection for tenants in our rental market means that socio-economically disadvantaged populations have become concentrated in poor quality housing.

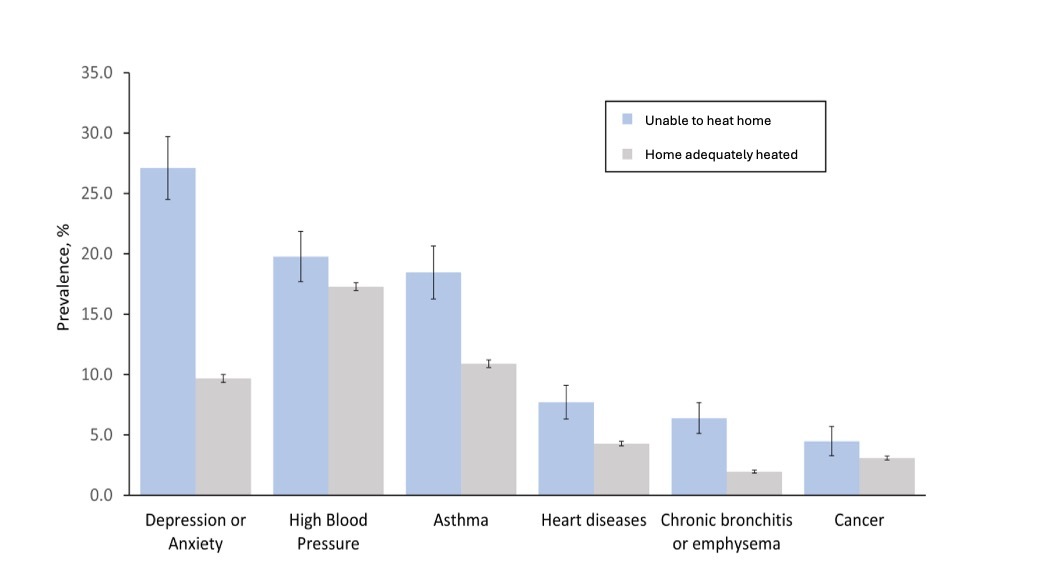

As a result, we see the people with the worst health exposed to the coldest indoor temperatures during winter (Figure 1). These same households are also more likely to experience energy hardship, meaning they cannot afford to adequately warm their homes.

And these systemic problems are contributing to a large mental health burden at a population level.

Put another way, our housing is not protecting population health as well as it could or should.

So, instead of concentrating research efforts on measuring thresholds, we need a better understanding of the complex nature of indoor temperature and poor health.

This, alongside a focus on the consequences of structural inequalities in our housing system, means research like ours can help to inform better policies in Australia when it comes to the link between housing and our health.