Rescuing Australia’s lost literary treasures

Have you ever gone looking for a particular book and discovered it can’t be found for love nor money?

If so, that’s no surprise. Most Australian books written are now out of print and unavailable to readers.

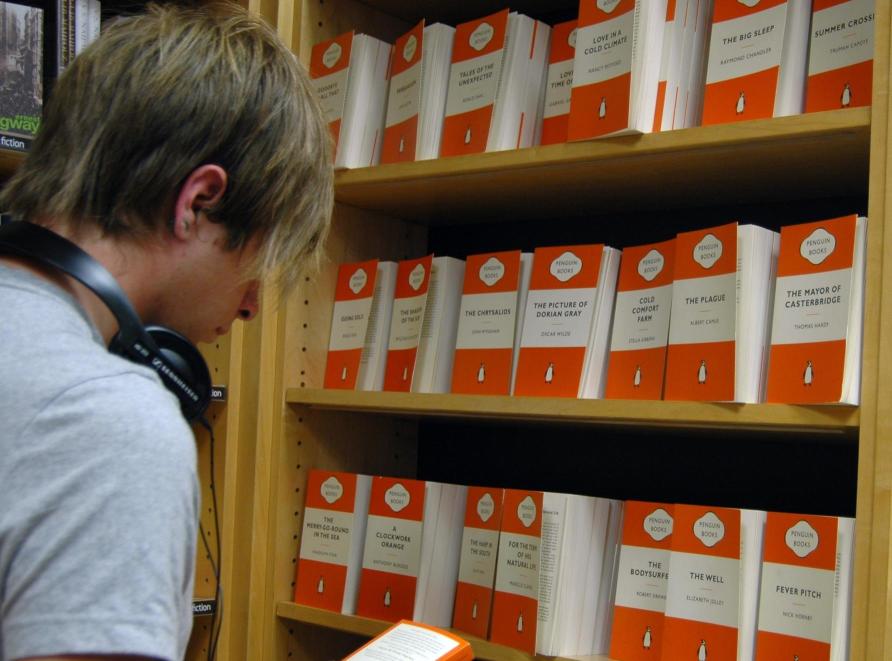

When we investigated the availability of past winners of Australia’s Miles Franklin Literary Award, we discovered that 23 weren’t available as ebooks, 40 weren’t available as audiobooks, and 10 weren’t available in Australia in any form at all.

These lost books include well-known titles such as Thea Astley’s The Acolyte and The Well-Dressed Explorer, Rodney Hall’s Just Relations and The Grisly Wife, and Dal Stivens’ A Horse of Air.

That books such as these can even go missing hints at the scale of the problem.

Australian literature’s great silence

Now consider what else is lost: local histories and memoirs, beloved children’s titles, the books that tell the story of our country and its people.

When books go out of print, authors usually have the right to reclaim their copyrights. But what then? Digitising books is expensive, and authors who make that investment and start selling them online (via Amazon, for example) often find that they sink without a trace.

And they can’t make them available in libraries, because those licensing arrangements are all built to go through publishers.

In a new collaboration between authors, libraries and researchers, we’re setting out to change all that.

Untapped: the Australian Literary Heritage Project is creating the infrastructure necessary to rescue Australia’s lost literary treasures and bring them properly back to life.

Working with a national team of library collections experts, we’re building a list of culturally important lost books, then working with authors to digitise them, license them into libraries, and make them available for sale.

Our library partners will then work hard to promote the books – recommending them to readers, featuring them on their e-lending websites, and setting up exciting initiatives like town or city-wide reads, where the locals are invited to all read (and talk about) the same book.

The enduring ‘cultural cringe’ about teaching Australian literature

As well as covering the digitisation costs (our library partners are funding the first batch), this will generate new revenue for authors, who will be paid when their books are borrowed. It will also support arts workers affected by COVID-19, who we’ll hire to assist with the proofreading work necessary to get the digital versions up to library standard.

As well as rescuing these lost literary treasures, there are important research motives for this work too.

Australian book authors have been seeing their incomes fall for years and, according to the most recent figures, earn an average of just $12,900 a year from their writing work.

Over the past three years, my team at the Author’s Interest Project (an ARC-funded Future Fellowship) has been working towards finding ways of improving authors’ rights to reclaim copyrights of under-exploited books.

But that will only be effective at improving incomes if there is a market for them. This project will help create one.

Working with cultural economists Dr Paul Crosby of Macquarie University and Associate Professor Imke Reimers at Northeastern University, the data for this project will enable us to add substantially to global knowledge about the economic value of reverted rights.

On top of that, this research will help libraries and publishers too.

The rise of the microgenre

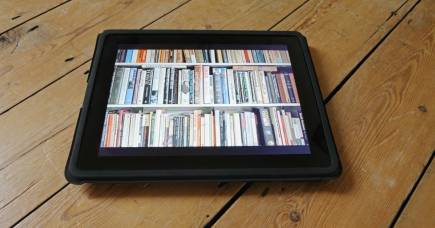

Libraries have been lending out ebooks for more than a decade, but the value of digital access to books has never been more evident than this year, as physical libraries shuttered and we were locked at home for months on end.

Unlike physical books, which can be bought and lent without the publisher’s permission, libraries do need permission to buy and lend ebooks.

But recently, Amazon has been fanning fears that library ebook lending might be cannibalising sales, and publishers, already under severe financial pressure (worsened, ironically, by Amazon ruthlessly squeezing their margins) have been growing nervous about making their books available.

All the available evidence demonstrates a positive or at least neutral relationship between library lending and book sales, but it is limited to surveys and self-reporting. That’s because Amazon (again) won’t make data about ebook sales, and lending data is only available to individual libraries.

Our project aims to fill this data gap.

By designing the experiment as we have, our research team will be able to access data about the sales of these books and how many times they’re licensed by libraries and borrowed by readers.

It will enable us to better understand the economic value of library promotion of books and whether e-lending in libraries actually does cannibalise or grow book sales. We’ll feed the results back to publishers and libraries, and into public policy discussions about how we can best support Australian authors and literary culture.

Since the results will inform knowledge about such urgent and timely questions, we expect it to influence public policy debates elsewhere in the world as well.

The next time you go looking for an important Australian book and discover that it’s missing, get in touch – maybe it’s one that we can rescue.

This article was first published on Pursuit. Read the original article.

Do you like to read the classics? Are you surprised that books of such importance need to be ‘rescued’?

If you enjoy our content, don’t keep it to yourself. Share our free eNews with your friends and encourage them to sign up.

Related articles:

https://www.yourlifechoices.com.au/finance/seniors-finance/time-to-rediscover-past-passions

https://www.yourlifechoices.com.au/lifestyle/leisure/activities/plant-craze-captivating-millions

https://www.yourlifechoices.com.au/lifestyle/leisure/activities/how-to-master-the-quiet-weekend