World Population Day is a United Nations observance on 11 July each year that aims to enhance awareness of population issues, including their relations to the environment and development.

With an easing of COVID restrictions and a new federal government, Australia is at a crossroads in its approach to population.

For much of the 21st century, successive Australian governments have championed the idea of ‘Big Australia’. This has meant that our population rapidly expanded from 18.9 million in 2000 to 25.5 million in 2020. At our peak, we were growing by about 2 per cent per year – well above the OECD average annual population growth rate. In 2019, Australia grew by nearly 400,000 – or the equivalent of the size of a new Canberra.

How did Australia’s population grow so quickly in these past two decades? Around 60 per cent of our population growth was due to net migration. Little more than 5 per cent of that net migration was due to Australia’s humanitarian intake (refugees, asylum seekers, etc).

However, much of the discussion on population has centred around the immigrants who make up this smaller figure of 5 per cent. The debate around refugees and asylum seekers divided the nation and often railroaded a broader and more nuanced debate about the costs and benefits to Australia of the much larger (95 per cent of the total) intake of ‘economic migrants’.

Meanwhile, all the major political parties were happy to drive hard and fast on Australia’s population growth without considering a long-term population policy.

There is still no policy that identifies an upper limit of Australia’s population, what to do after this has been reached, and how to properly address the social and environmental impacts that result from rapid population growth.

Big Australia was (and still is) encouraged by many, including most economists and lobbyists from the big business community. This is perhaps of little surprise to anyone, given that more customers is often better for business than fewer.

Perhaps more surprising is the almost unanimous support for Big Australia from the left-leaning side of politics. Despite its implications for environmental deterioration, Big Australia offers promises of ‘diversity’, ‘vibrancy’ and the belief that open borders are more conducive to the social justice values held by many on the political left.

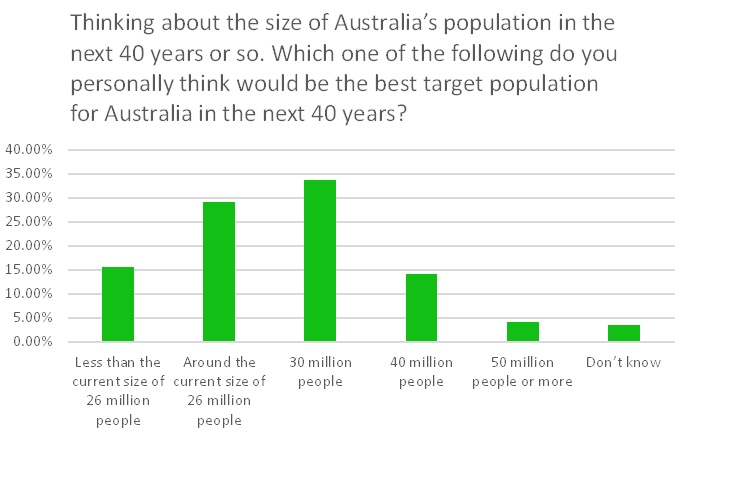

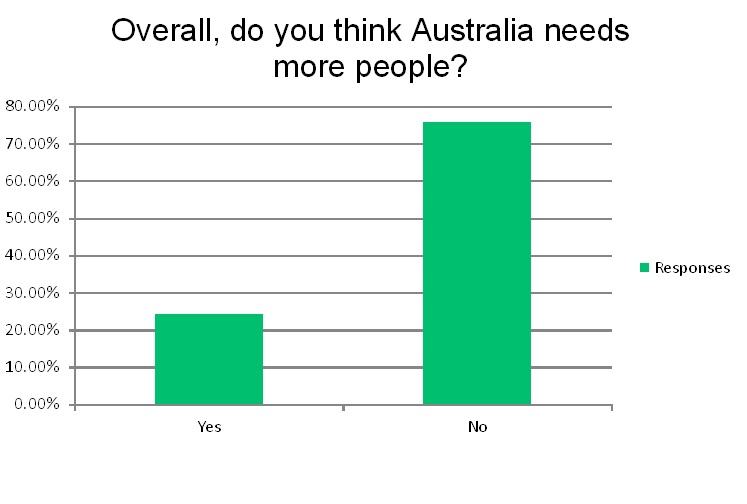

However, not everyone is a fan of a Big Australia. Opinion polls consistently show that a large majority of Australians believe the nation does not need more people and that Australia’s population should not grow beyond 30 million.

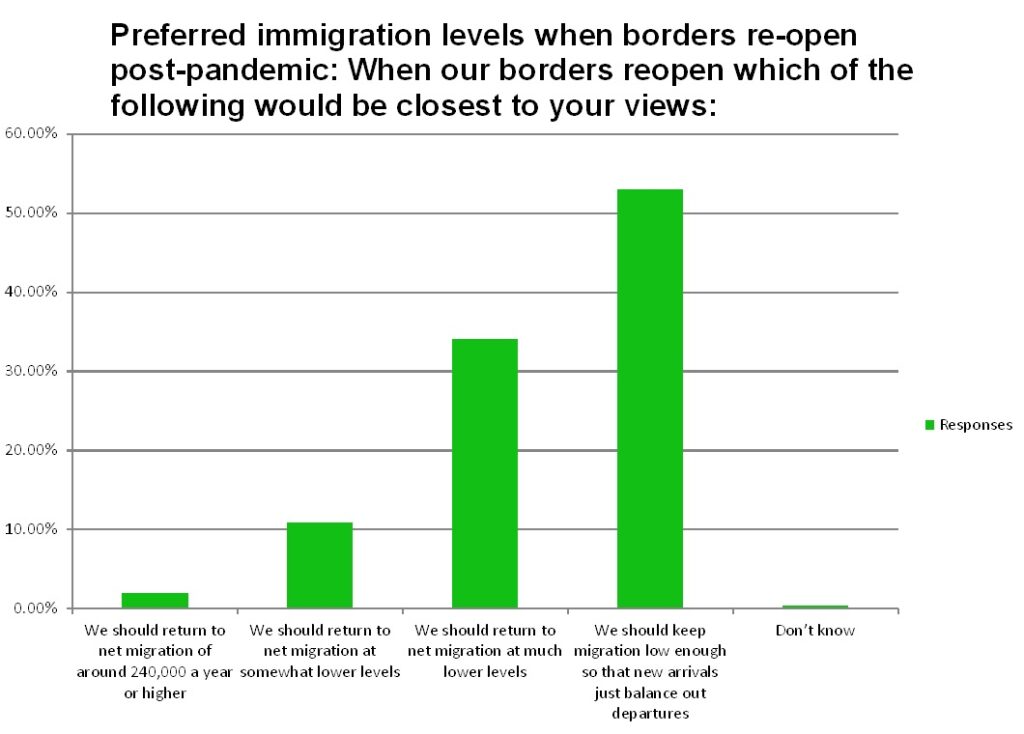

Indeed, similar results were obtained in the recent YourLifeChoices poll on this topic. This expressed preference of Australians for low or no population growth is a far cry from the official projections that anticipate Australia growing to close to 40 million by mid-century.

What are the main reasons that turn most Australians off from the Big Australia narrative? Traffic and public transport congestion are commonly raised issues, as are lagging healthcare and other public services.

These are all symptomatic of the broader issue of infrastructure failing to keep up with the rate of population growth. The reasons for this are detailed in the Sustainable Population Australia (SPA)-commissioned discussion paper: Population growth and infrastructure in Australia: the catch-up illusion.

Other issues that are raised include housing availability and affordability, increasing competition in the jobs market, urban sprawl and overdevelopment in our cities and towns and last, but definitely not least, the heavy toll on the natural environment.

Contrary to ill-informed claims that wanting low population growth is somehow racist or ‘nativist’, concerns regarding social cohesion or ethnic make-up of our population growth have never predominated.

So, who is right? Is it our big business and our politicians who champion Big Australia with the lure of jobs and growth? Or do the growing number of people wanting our numbers to stabilise have a point?

In March 2020, we had the opportunity to put this theory to the test. Or rather, the test was imposed on us via the first wave of COVID. Since then, our borders have been either fully or partly closed with a subsequent pause on migration. Population continued to grow at a national level, but at a much slower rate. According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, Australia grew by 0.5 per cent in each of 2020 and 2021, with natural increase (births over deaths) being the dominant driver.

Now that the borders are re-opening, there is growing pressure from government and business to return to similar levels of economic migration and population. But it is worth reflecting on what gains and challenges this period of lower population growth brought to Australia.

The most notable difference is that employment and wage conditions for workers improved. According to a briefing note commissioned by Sustainable Population Australia:

“High levels of immigration in the decade pre-COVID-19 contributed to stagnant incomes growth, lower incomes and employment prospects for both skilled and unskilled Australians, and detracted from the living standards of many Australian working families.”

A wide range of economic commentators, including Reserve Bank head Philip Lowe and Professor Ross Garnaut, have drawn attention to the contribution that low immigration has made in lowering unemployment and encouraging employers who previously relied on migrant workers, to take on Australians. This is better news for younger generations of Australians.

On the other hand, some businesses have struggled with the challenges of employing sufficient staff. However, there are other contributing factors to take into consideration, such as COVID, which affected staff retention.

What about the economy? GDP is a precarious measure of success, even though politicians and the business community swear by it. It is also claimed that population growth underpins GDP growth. However, recent experience counters that claim. GDP continued to grow during the pandemic and is anticipated by some to continue to grow.

The housing market has also remained strong. It was expected that house prices would slump after the borders closed. Until recently, house prices defied expectations and continued to climb for a number of reasons. One example is that urban-rural drift away from the capital cities increased demand in regional Australia. Another is the spending habits of landlocked Australians during the pandemic, in a situation of low interest rates (until recently), where many people were more inclined to spend more on housing.

However, there is an indication that the housing market was sustained by past momentum and there are strong signs the market is starting to cool. In fact, house prices are beginning to fall in Melbourne and Sydney.

The housing crisis has become entrenched over the past few years, with more people being unable to afford adequate housing in this country. It is worth considering how much worse the problem could have been had there been an extra 200,000 or so people each year competing in the housing and rental markets.

This is something we will need to consider further if we are to open our borders and return to high economic migration numbers – particularly considering that some areas of Australia that have been becoming more populated, are being rendered increasingly uninhabitable by a relentless string of extreme weather events.

Collectively, we have a choice to decide our future and send a message to the politicians (and their big business donors) regarding the size that we want our country to be moving forward. Every path has its pros and cons. Each path will have implications for how well we can sustain our size and our lifestyle choices within the limits of finite resources and the carrying capacity of the natural world.

What would be the pros and cons of a bigger Australia moving forward? There may be benefits for employers due to the higher job application-to-position ratio, and the downward pressure this has on wages.

For those of us whose post-retirement income may depend, at least partly, on ever appreciating land value, increasing populations increase the demand for housing, therefore making it more likely that house prices may continue to increase in the future.

For those of us in the construction and civil engineering industries, sustained population growth guarantees demand for more roads, infrastructure etc.

What then are the benefits of a less big, or smaller Australia? Quite a few. The employment and future earning potential for young people entering the workforce is greatly improved as is the benefit of older Australians re-entering the workforce.

Housing security – a basic human need – may become more possible for younger generations if there is less competition for existing housing stock.

Also, essential services, such as our hospitals and healthcare industries, may have room to breathe and catch up if population rate slows.

COVID brought home a stark reality that has been brewing for many years – that our health and aged care sectors are simply failing to keep up with demand. It is difficult to look forward to the golden years if the reality means that services are cut and spread thinly across more of us.

This is all underpinned, whether we like it or not, by the long-term health of the natural environment that sustains us.

Unfortunately, the latest State Of The Environment report (which the previous federal government was accused of sitting on and which is still pending release) is set to paint a pessimistic outlook of Australia’s environment. As this article is being written, large parts of Sydney are once again being hit by flooding.

If this is just a taste of our future, the question remains: how we are going to house our existing population safely in the coming decades, let alone another 10 million by 2050.

The benefits of a stable population size to slow Australia’s growing greenhouse gas emissions is another compelling reason to rethink Big Australia. As detailed in a recent paper by eminent scientist (and SPA patron) Professor Ian Lowe, Australia’s total greenhouse gas emissions from energy have risen 49 per cent since 1990 due entirely to population growth of 8.3 million people.

As Prof. Lowe says: “The future is not something you go to, it is something you make.”

What is the future for Australia’s population that you would like to see, all things considered? More? Less? About the same? Continue the conversation by sharing your thoughts and reasons in the comments section below.

Michael Bayliss is communications manager for Sustainable Population Australia (SPA). SPA has a media release for World Population Day 2022 that can be read here and a podcast episode you can listen to here. To find out more about SPA, visit the website here.