In the late 1990s, Stanley Kubrick was on the set of Eyes Wide Shut – a divisive, erotic drama that would be his final film. One scene required Sydney Pollack, an experienced actor in a minor role, to walk across a room and open a door. A first-time collaborator with Kubrick, Pollack made the grave mistake of asking the director how he wanted this done. “I don’t know Sydney,” he replied, “you tell me.”

Two whole days and hundreds of door openings followed, after which an exhausted and exasperated Pollack asked what else he could possibly do. “Well Sydney,” said Kubrick, “I didn’t think it would take this long, but don’t you want to get it right?”

The episode is typical of a man widely considered a genius, mostly for his filmmaking, but also for personifying the public image of what a genius is expected to be.

Extraordinarily secretive, agonisingly perfectionist, and fabulously enigmatic – Kubrick required total control over script, style and sound, and disavowed every production in which this was denied. He never gave interviews, was so afraid of flying he wouldn’t film overseas, and spent his days ensconced behind the electronically locked gates of his mysterious Hertfordshire mansion.

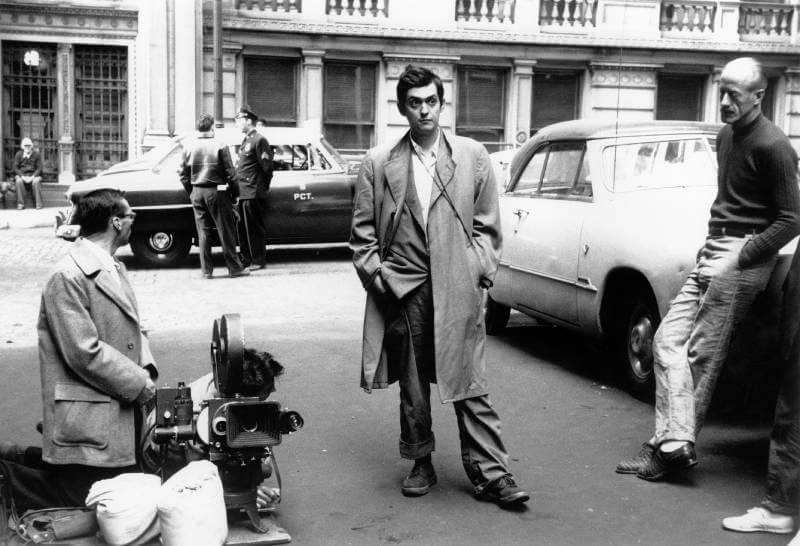

He made his first film partly with his winnings from a chess competition, and thereafter released just 12 features in 45 years. Here, we take a look back at the life of one of cinema’s most celebrated visionaries.

The man in the chair

As a filmmaker, Kubrick did not take inspiration from the great practitioners of his art. Indeed, he took greater encouragement from incompetence. “I believed that I couldn’t make them any worse than the majority of films I was seeing,” he once said. “Bad films gave me the courage to try making a movie.”

Though many of his works are now top-10 regulars, his career had a rocky start. He roundly derided his first feature – 1953’s Fear And Desire – as “a bumbling, amateur exercise”, and later went to great lengths to ensure it wasn’t seen. A Killer’s Kiss, The Killing, and Paths Of Glory followed, finding favour with critics but not with the paying public.

In 1959, he helmed swords-and-sandals epic Spartacus, at the request of its A-list star Kirk Douglas, who denied him the control to which he was already accustomed. Next came a wildly ambitious adaptation of Lolita – Nabokov’s story of a sexual relationship between a middle-aged professor and a pubescent girl – which was savagely cut by the censors. For Kubrick, both projects were tainted by frustration, and both were promptly disowned.

Young British actors and directors are often enticed across the pond by the bright lights of LA, but for Kubrick it was the other way around. Disillusioned with Hollywood, he fled America for the English countryside in 1962, and never looked back.

Kubrick unleashed

Finally, safe from the tycoons of Tinseltown, Kubrick set about making movies his way. His style switched from naturalistic to obliquely surreal, while his storytelling began to betray a marked pessimism about the human condition. He picked up visual trademarks – long corridors; Steadicam tracking shots; geometric, frame-by-frame composition – and pioneered new methods for shooting in low light.

1964 brought the triumphant release of Dr. Strangelove, a jet-black Cold War farce that spat at the popular Hollywood narrative that adversity brings out the best in people. Four years later came 2001: A Space Odyssey, a vastly over-budget sci-fi epic spanning the whole of human history, a magnum opus that overwhelms the senses with a swirl of kaleidoscopic existentialism.

It ranks alongside Citizen Kane, the Rite Of Spring, and every painting by Vincent van Gogh as a masterpiece that was not wholly appreciated in its time. At the New York premiere, many of the audience walked out, others jeered, and one prominent critic declared it “the biggest amateur movie of them all”.

In a strange quirk of history, cinephiles may have hippies to thank for the film’s success. Stoners flocked to the film in droves, and for a while John Lennon claimed to catch a showing at least once a week. The marketing execs soon caught on, and the second round of promotionals bore an extra tagline: “The ultimate trip.”

Now firmly fixed among the great masterpieces of 20th century cinema, it seems almost too easy to say that 2001 was ahead of its time.

A career chameleon

Kubrick was a man for all genres, and with a portrait of a paedophile and an apocalyptic comedy already under his belt, he was developing an uncanny habit of filming the unfilmable.

After the exorbitance of 2001, he wanted to prove he could handle a low budget, and decided to do so with the Beethoven-fuelled ultra-violence of A Clockwork Orange. Based on the eponymous novel, the film was a box-office hit, but gained unwelcome notoriety after it was cited by defendants in several rape and murder trials. Kubrick promptly pulled the film from UK cinemas, and it was not theatrically re-released until after his death (in 1999, aged 70, mere days after a final cut of Eyes Wide Shut was screened).

His next offering – costumed period piece Barry Lyndon (1975) – could barely have been more different, but Kubrick still managed to scope out trouble. He unwisely shot scenes in Ireland featuring uniformed British redcoats. Following death threats from the IRA, he fled to England by ferry under an assumed name.

Though not his most enduring work, this slow-paced drama became synonymous with visual authenticity. Kubrick used satellite lenses to shoot indoor scenes by candlelight, and penned a now-famous letter to American projectionists with detailed instructions on how the film was to be shown. “An infinite amount of care was given to the look of Barry Lyndon,” it read. “All that work is now in your hands …”

A ‘method’ director

Giving others responsibility was not something Kubrick did if he could avoid it, and “infinite amount of care” was perhaps an understatement. “No matter what it is,” said A Clockwork Orange star Malcolm McDowell, “even if it’s a question of buying a shampoo, it goes through him.”

He paid real aeronautics engineers to design the set for 2001 (including a $300,000 centrifuge), temporarily blinded McDowell shooting the infamous Ludovico Technique scene, and insisted the tabletops in Dr. Strangelove be green, despite shooting the film in black and white.

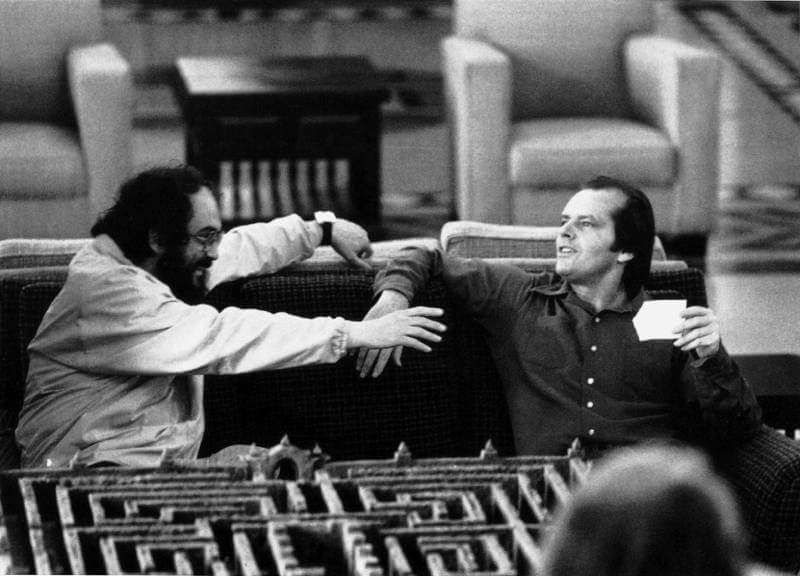

The demands he placed on his actors were legendary, and often interfered with their wellbeing. Most famous by far is his treatment of Shelley Duvall – on the set of 1980 film The Shining, he exhausted and belittled her so systematically that her on-screen hysteria was barely put on.

In the notorious ‘staircase scene’ (in which Duvall backs away from an advancing Jack Nicholson weakly swinging a baseball bat), her bloodshot eyes, pathetic whimpers and feeble swipes come mostly from the fact that it was take number 127. “If you did a film with Stanley, you were married to him,” recalled Shining co-star Philip Stone, “there was nothing else in your life.”

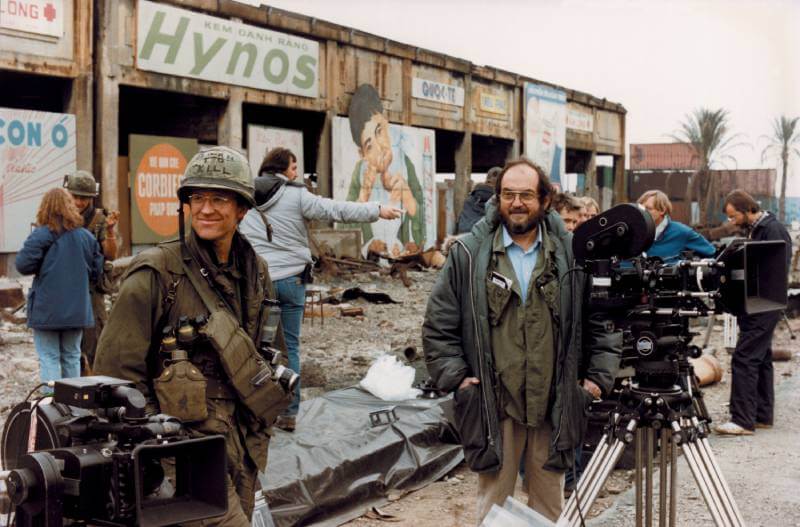

In his later years, productivity slowed to a crawl. 1987 brought nihilistic ‘Nam flick Full Metal Jacket – best-remembered for R Lee Ermey’s fabulously foul-mouthed drill sergeant – and Eyes Wide Shut followed 12 years later. Kubrick died suddenly in 1999, a few months before the film went on general release.

The cult of Kubrick

It’s easy to see how Kubrick attained semi-mythic status, but Christiane, his wife of 41 years, has since sought to straighten the record.

“He was sad about all the stuff those people wrote about him,” she told The Guardian in 2005. “All those awful stories … that he was phobic, obsessive, weird. I flinch when I see all these things about Stanley the so-called crazy man.”

On set, she admits he was, shall we say, meticulous, but at home she paints a picture of a committed family man. “He was immensely gregarious – not like they always say… [and] he was a great dancer.”

What do you think of Stanley Kubrick’s work? Let us know in the comments section below.

Also read: Hillary Clinton and other politicians who’ve tried their hand at fiction

– With PA