During her 27 years in the British prison service, Vanessa Frake encountered some of the most notorious criminals Britain has seen, including Moors murderer Myra Hindley and serial killer Rosemary West.

She was bitten and punched by violent prisoners, dealt regularly with inmates who embedded razor blades in toothbrushes or made deadly clubs from pool balls stuffed into socks.

But her worst experience was when she was showered from head to foot with human excrement in a practice known as ‘potting’, where a prisoner shovels their faeces into a plastic bottle and then chooses an opportune moment to hurl it at their victim.

Happy world book Day. Looking forward to this book being published #thegovernor #15thApril2021 pic.twitter.com/L8hXPwiHk8

— VFH (@VanessaFrake) March 4, 2021

“It was the intended humiliation that was difficult to cope with,” she recalls, “which is why I got a fresh uniform and went straight back to the wing. Nobody was going to have me over in that respect.”

Staff members were, understandably, always on their guard, she recalls. “You are trained for it. You were taught how to de-escalate situations, how to defend yourself and interpersonal skills to talk your way out of trouble. I got assaulted, but so did a lot of other prison officers.”

Ms Frake, 59, who retired from the prison service in 2013, is clearly tough, with a no-nonsense approach and fearless attitude that saw her rise through the ranks as she engaged in daily battles of wits with inmates. First working as a junior prison officer at Holloway, the high security women’s prison, and later as the governor of security and operations at Wormwood Scrubs, which housed some of the most violent male criminals, Ms Frake has seen it all.

She recalls many of her experiences in her memoir, The Governor, in which she charts her life inside Britain’s most notorious prisons.

Read: How do police forensic scientists investigate a case?

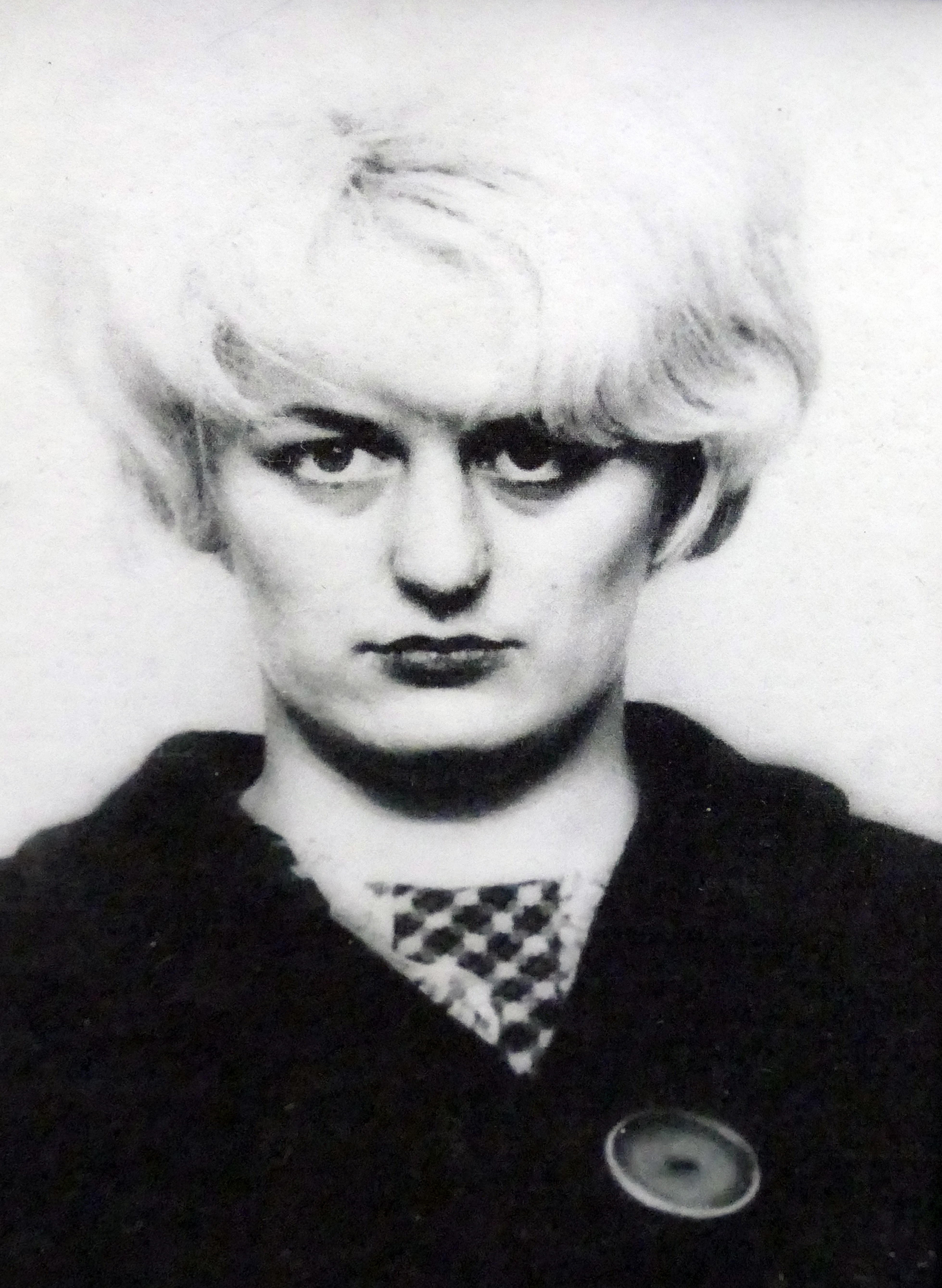

In her early career, while escorting four prisoners to HMP Cookham Wood, she encountered Myra Hindley, unaware of who she was, who made her a cup of tea. “I didn’t recognise her. You automatically think of the pictures of the bleached blonde hair, the intense stare, the bob – and she didn’t look anything like that. These people look as normal as the next person.”

Rose West was constantly knitting while on remand at Holloway while awaiting trial, Ms Frake recalls. “When I first met Rose West we were expecting this horrendous monster who was going to come in and demand this and that, but she was quiet. You could see she was taking it all in. She looked like the auntie you’d have a cup of tea with on a Sunday afternoon.”

Ms Frake was present when Ms West was told her husband, Fred, had killed himself in prison, and was surprised at her response. “Nothing had altered in her expression. No tears, no nothing, just that glazed stare. The level of control and disassociation was staggering,” she recalls.

Later in her career, at Wormwood Scrubs, celebrity inmates proved a headache. She didn’t like Pete Doherty, frontman of The Libertines and one-time boyfriend of supermodel Kate Moss.

Mr Doherty, she recalls, was difficult. He was serving a 14-week sentence at Wormwood Scrubs in 2008 for breaching his probation, when she met him. “He was a drug addict and that in itself causes issues, but he wasn’t the most helpful of prisoners. I’d never heard of him. He was young and cocky, loved all the attention from other prisoners,” she recalls.

“He was demanding this, that and the other – expecting special treatment because he thought he was something special,” she writes in the book. “With certain prisoners, it was difficult dealing with their solicitors, their MPs, the likes of Lord Longford with Myra Hindley, their political minders.”

Ms Frake was never scared, though, because of the camaraderie. “If you know that an officer you’re working with has got your back, you can deal with it. And if I had ever been scared, then I wouldn’t have been able to do the job. Your body switches on the adrenaline to get you through things that day-to-day people would never see.”

She admits that over the years she became desensitised to the horrors she encountered in her job. “You deal with attempted suicides and self-harm on a daily basis and don’t bat an eyelid, but when you sit back in retirement and your body starts to relax, you think about things and it becomes more of an issue to deal with.”

The one event for which she still harbours guilt was a prisoner escape. The convict, who was writhing around in apparent agony from a mystery illness, was taken to hospital on the doctor’s insistence, even though Ms Frake was not convinced.

On arrival at the hospital, the ambulance was ambushed as two armed men wearing balaclavas threatened the three prison staff escorts at gunpoint before fleeing with their criminal pal. The prison officers were left in a severe state of shock and despite the fact no-one was hurt and the prisoner was caught three days later, Ms Frake still feels regret.

“I know that the staff went through horrendous post-traumatic stress with that, to have a gun pointed in your face, I can’t imagine how they felt. That did affect me and still does. I always feel guilt,” she says.

Read: How focusing on the positives can help your mental health

Throughout her career, drugs were the greatest problem within prisons, she reflects. They were commonly hidden in food packages until the law changed whereby only clothes, paperback books and magazines are allowed to be gifted to prisoners.

Somehow, prisoners managed to get them in and used increasingly clever ways to do it, not just the tennis ball or dead pigeon thrown over the wall by a willing supplier.

View this post on Instagram

On one occasion, an astute member of staff traced a thin fishing line from a prisoner’s window bars to a nearby hospital roof. Accomplices on the outside had been using it as a zip wire to smuggle drugs into the prison.

Ms Frake went so far as to have bird netting installed around prison buildings at the Scrubs, to ensure drugs packages couldn’t land inside. Her initiative drastically reduced the MDT (Mandatory Drug Testing) rate to become the lowest of all the London prisons.

“Drugs continue to be a problem in prison because you shut one door and another one opens,” she says now. “Now there are drones, but they weren’t invented when I was in the service.”

Ms Frake now lives a quieter life in Saffron Walden, Essex, with her partner, Julie Harris, who she married in 2014. “I didn’t find retirement easy,” she admits. “I missed the banter, the camaraderie and learning new things. I shut the prison service up in a box and I was looking at four walls thinking, ‘What do I do now?’ I didn’t want to sit and watch TV.”

Read: Why retirement planning must be personal

She suffered panic attacks in the years after retirement, having spent so long in such a structured and disciplined world, compartmentalising her life. “I went to the doctor and completely broke down,” she recalls. “It was a relief to get it all off my chest and have somebody there to listen to me. I was put on anti-depressants for a while.”

These days, baking is her pick-me-up in her job at a local café, while she also volunteers at an animal sanctuary. “My demons have been dealt with now. Having written them down and talked about them and spoken about the emotions, a great weight has been lifted off my shoulders.”

View this post on Instagram

The Governor by Vanessa Frake with Ruth Kelly is published by HarperElement, available now.

– With PA