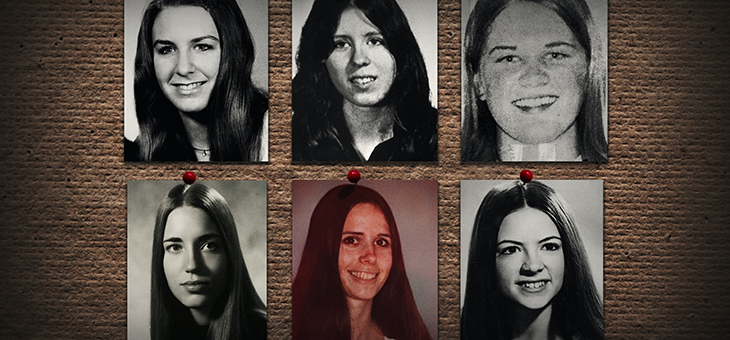

Serial, Making a Murderer, The Teacher’s Pet – all these shows have one thing in common. Yes, they’re all hugely popular, but we’re talking about something else, they all centre on the gruesome murder of a woman.

Whether it’s a TV show or a podcast, our craze for murder investigations is reaching fever pitch. Considering the grisly nature of these shows – particularly how more often than not it involves violence against women – our collective obsession is a curious psychological and social phenomenon. It’s like a car crash – brutal yet we can’t look away. The craze arguably started back in 2014 with the first season of the podcast Serial, exploring the death of teenager Hae-Min Lee.

But why is our attention so captured by these kinds of stories? With the popularity of true crime showing no signs of slowing down, we asked psychologist Meg Arroll what it all means.

It allows us to be voyeurs

Humans are naturally curious beings, and we’re particularly interested in lives completely removed from our own. Why else do you think celebrity culture is such a huge phenomenon? We’re obsessed with finding out about things we don’t know – the more salacious the better.

“True crime allows us to be voyeurs. Yes, to truly horrific acts, but this is the point,” Ms Arroll explains. “It’s modern-day curtain twitching, nosing on what your neighbour is up to and having an opinion on other people’s behaviour. In animals that live in groups, such as humans, being curious has an evolutionary advantage – knowing what others are up to allows you to be prepared for any challenges.”

While we’re probably not preparing for the grisly situations in these shows, this curiosity is still part of our evolutionary make-up and adds to the appeal.

We get to experience danger from the safety of our sofas

Sure, we’re interested in exciting and perilous things – but most of us don’t have death wishes. Instead, we get to experience the ‘thrill’ of these shows from relative safety.

“The vast majority of us will (thankfully) not be party to any of the serious crimes in series such as Making a Murderer,” explains Ms Arroll. “The way these programs are edited takes us along with one of the real-life protagonists, especially in the shows that uncover alleged miscarriages of justice. We feel the highs and lows, but in the safety of our own homes.”

We begin to feel emotionally invested in the story, and swept up in the drama and excitement because it’s so far removed from our daily lives – and we’re actually in no imminent danger.

It reminds us of right and wrong

“The mass uproar at both crime itself and then a miscarriage of justice is also important for our social norms – the knowledge of what is right and wrong allows us to live together in a society,” says Ms Arroll.

Most popular examples of true crime don’t have a clear outcome, but one thing we do know for sure is that something bad has been done. “Being able to point the finger at a wrongdoer and chastise them maintains societal norms,” Ms Arroll says. “We have a keen sense that wrongs will be righted, and the bad guys will get their comeuppance.” Unfortunately, life isn’t always like this – these aren’t fairy tales but actual events that have happened, so the desired outcome isn’t always achieved.

Sometimes viewers or listeners are offered a kind of closure and this in itself is a reason enough to persevere. In Australian podcast The Teacher’s Pet, the main suspect was arrested and charged at the end of last year, nearly 37 years after the crime. “Ends are neatly tied-up, which offers a sense of satisfaction and comfort not often found in our actual lives,” Ms Arroll says, but she adds: “Of course, the people in these shows rarely experience this closure and their lives are marred, court battles drag and families are shattered.”

But it has the danger of desensitising us towards violence

True crime programs are making millions for production companies, but what are the potential ramifications of our obsession with murder investigations?

“These narratives are not new, but the grisly nature of such shows and podcasts might be construed as a desensitisation to violence, which is not a positive outcome,” Ms Arroll explains.

The majority of these shows revolve around violence against women and it’s not surprising when you look at the statistics. On average, at least one woman a week is killed by a partner or former partner in Australia. One in three Australian women has experienced physical violence since the age of 15. Because most of the cases investigated in these shows search for maximum intrigue, the majority of victims knew or were in a relationship with their killer – which is statistically more likely to happen to a woman.

Constant storylines of violence against women is a divisive issue. On the one hand, it could be said to raise awareness around the scarily common issue of violence against women. It could also, in a way, be helping. A 2010 study by psychologists at the University of Illinois suggested that such tales help women deal with misogyny and violence.

On the other hand, there’s the frightening possibility that the popularity of these shows is at the very least desensitising us towards violence against women, or at worst normalising it. The shows that fall into the latter category are those which barely give the female victim a voice or a ‘character’, almost ignoring her and instead focusing on the male suspect.

If you love the investigative nature of true crime shows but want to do away with all the violence, try listening to Last Seen – a podcast looking into the mystery of one of the world’s biggest art heists. It’s got mystery, suspense and glamour – and not a dead body in sight.

Are you a fan of true crime? Or do you do your best to avoid the grisly tales?

– With PA

If you enjoy our content, don’t keep it to yourself. Share our free eNews with your friends and encourage them to sign up.

Related articles:

https://www.yourlifechoices.com.au/how-podcasts-exercise-your-brain

https://www.yourlifechoices.com.au/why-were-obsessed-with-nostalgia

https://www.yourlifechoices.com.au/news/are-you-listening