Our country, Our way

As a kid, I grew up in the city, but I was always out in the bush a lot. I always found a sense of belonging out in the bush, out on country.

That sense of belonging to country has shaped me in one way or another throughout my life.

It’s something that drives me in my research, in connecting people, not only us Aboriginal people to country, but all of Australia to country.

Professionally, I’m a geographer, in particular I focus on the patterns and processes that shape the world around us. I extract sediment cores, I look at the layers of the earth and unpack the information that is stored in the layers of the earth to tell a story about how landscapes and environments have changed.

One of my key focuses is how people shape, create, maintain and manage landscapes through time. And how is the present landscape that we live in shaped and created by human activity.

The climate legacies in our lakes

We need to understand the historical sequence of events that have produced modern landscapes if we hope to manage, maintain and live on and in the country we live in.

Australia faces a number of environmental crises right now.

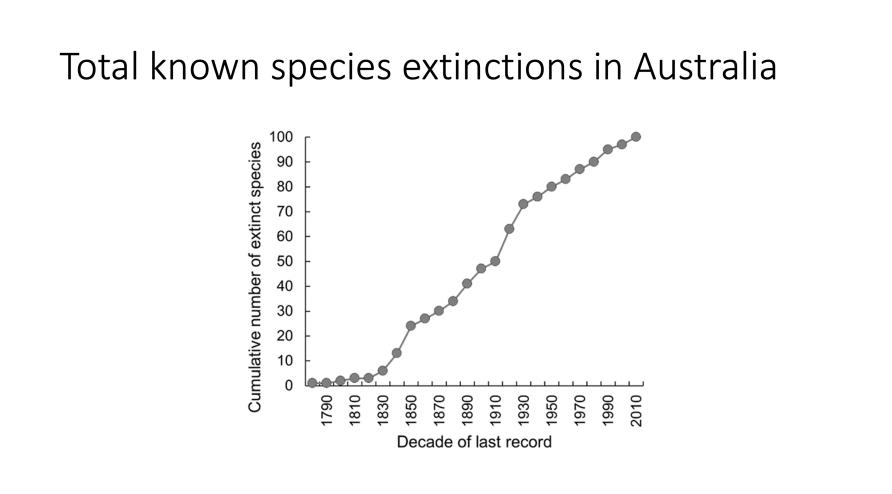

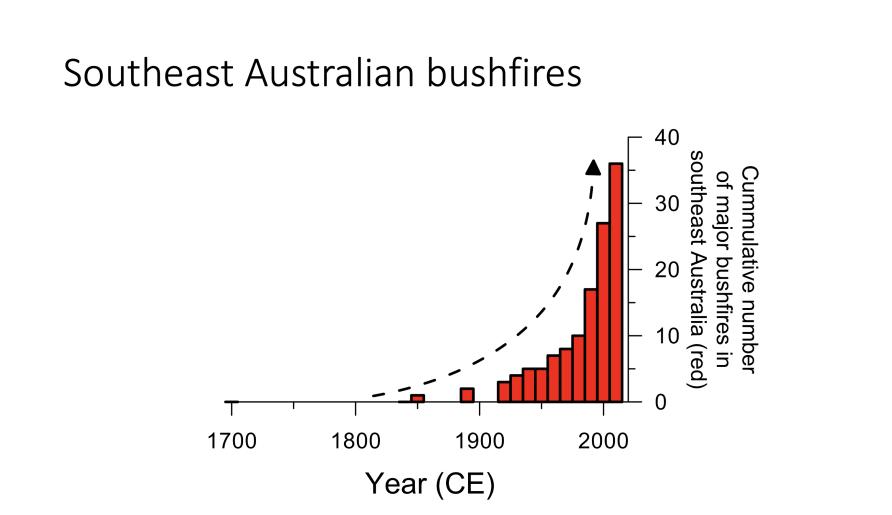

We have one of the fastest rates of biodiversity loss on Earth. Species have been going extinct in this continent since the late 1700s. We also are experiencing, particularly in the southeast, but all over our country, an accelerating rate of catastrophic bushfires that are becoming more frequent, more intense and larger.

I feel like we are constantly traumatised by things like catastrophic bushfires, by environmental tragedies like the loss of the Great Barrier Reef or mass deaths of fish in the Murray-Darling system.

So how did we get here? Well, it’s my contention that many of the environmental problems that Australia faces today can be traced to the devastating and continuing effects of the British Invasion and subsequent colonisation of the Australian continent.

Fire was first used by humans, or our progenitors Australopithecines, 1.7 million years ago, and the evolutionary trajectory of humans or hominids is inextricably linked to fire. It’s been our main tool and still is our main tool for landscape management.

Fire has also been critical in shaping who we are.

Why are our rainforests burning?

It has unlocked the potential of our food to power this immensely energy demanding organ that defines Homo sapiens. It’s enabled us to extend our waking hours beyond the rhythm of day and night, sitting around a campfire, conversing, talking in abstract terms, planning.

And it’s also changed many parts of our physiology. The requirements of our body to procure food, move around landscapes, control landscapes has influenced our form and structure from our body structure to our teeth. We are a fire organism.

People arrived here being fire users, intelligently using fire in the landscape. Then we have the subsequent 68,000 years at least of people living in Australia using fire to manage country.

So, what does it mean to manage country?

Well, landscape management is designed around three key purposes. It’s to create a predictable, bountiful and safe environment around us. The guiding principles of any kind of landscape management is to get predictability in the landscape, to create resources or resource availability in a landscape and to provide a secure place to live.

This is scientific knowledge. This is knowledge that’s been gathered scientifically. Indigenous knowledge is science. It’s gained by observation, executing a plan, observation, refining your plan, executing a plan, observation.

This accumulated knowledge of 68,000 years, more than 3000 generations of people, has seen the passing on of how to live on country.

Learning to live with fire

Yet this knowledge of how to live on country faces challenges. Now, you might assume this challenge comes from the overtly racist, the deniers, the history revisionists, those who seek to and cannot recognise that Aboriginal people are humans.

But the challenge comes from both sides. And perhaps more insidiously, from those who purport, and espouse an empathy for Aboriginal culture and the impact that the British Invasion has had on us.

I’m referring to the wilderness or conservation movement.

If we think about what ‘wilderness’ is, it’s an idea that is born from a European ideology, European epistemology. It means an uncultivated, uninhabited and inhospitable region.

It’s rooted in the idea that to be human, you must have a built environment, you must have large crop plants, you must have high population density, night-time lights, all of those sorts of things. It ignores the fact that people live on country, influence country and influence environments in all sorts of ways that don’t include these very discrete and narrow set of factors.

This ideology of wilderness destroys country in Australia.

So, you end up with this irony, where a large sector of the conservation or wilderness movement – many of them the same people who espouse the need to shift to more sustainable ways of living – ignore consciously or not the very cultures that can show them the way of how to live sustainably on country based on accumulated knowledge over thousands of generations.

How do we protect our unique biodiversity from megafires?

And in many ways, this is dehumanising.

In Australia, this has a deep history. A deep, deep history. The whole premise of terra nullius is based on the fact that Aboriginal people weren’t seen as humans.

So, it’s no wonder that modern Australia has trouble understanding the profound influence that Aboriginal people have had on the landscape.

Aboriginal people were managing country right across Australia. In southeast Australia, Aboriginal people were systematically massacred. People were removed from country.

We still maintain a strong connection to country. And we’re still here. But this resulted in a massive disruption to our management of country.

Shrubs and trees have increased across the landscape, resulting in high fuel loads. So that when climate shifts, when droughts occur, when we have high fire weather or extreme fire weather, the fires are getting larger and larger. And hotter and hotter.

We’re also experiencing the fastest rate of biodiversity loss on Earth, which began at the British Invasion and has continued apace since then and now is compounded by the impact of climate change. This is because people are no longer managing country.

We need people back on country.

Safeguarding our shared cultural heritage

We understand that if we care, look after, and fulfil our obligations and responsibilities in our country, we benefit, and country benefits, and we are both healthy.

In terms of fire, there’s reduced landscape fuel loads, less connectivity between the ground and the canopy, so you don’t get these big catastrophic fires.

I would argue, that a large part of the problem – environmental and social – that modern Australia faces, stem from our inability to connect properly with the country we live in. The importation of European ideas, the attempt to convert this country into another place, the inability to embrace and accept where we are and what it means to be on country in Australia, on country in this country.

This is really obvious in our attitudes towards fire. The whole language and attitude around fire is fighting fire. But fire is integral to the Australian landscape. And the futile attempt to fight it is just creating more and more problems.

And the people, the humans, who you need to engage are here. We’ve been here for 68,000 years, if not more.

You need to engage with us, to help you through this, to help all of us through this, to help heal the country and heal the people, heal the scars that large parts, if not all of Australia, have experienced following the repeated catastrophic bushfires that tear through this country and rip people’s lives apart and destroy biodiversity.

Is Our Story respected and valued?

We need to trust Aboriginal people. This is a big one.

The public needs to embrace Aboriginal people and Aboriginal knowledge, and the media has to wake up. It needs to cast off antiquated notions of wilderness, antiquated notions that country is better off without people, notions that we can win a war against fire.

We need to know that this country needs fire.

I think, importantly, we need to educate ourselves and educate our children. They’re the ones who will steer us out of these problems.

We need to educate them on the way this country needs to be, the way this country can be, and about the people who created this country.

This is an edited extract of Associate Professor Michael-Shawn Fletcher’s 2020 Narrm Oration – the University’s key address that profiles leading Indigenous peoples from across the world in order to enrich our ideas about possible futures for Indigenous Australia. A full version of the Oration is available here.

Banner: Getty Images

This article was first published on Pursuit. Read the original article.

Do you believe there is a lack of trust in the land management skills of our Indigenous people? Has Australia been too slow to make use of those skills?

If you enjoy our content, don’t keep it to yourself. Share our free eNews with your friends and encourage them to sign up.

Related articles:

https://www.yourlifechoices.com.au/lifestyle/learning/mangled-language-i-just-cant-tolerate

https://www.yourlifechoices.com.au/health/brain-health/lifestyle-changes-that-beat-alzheimers

https://www.yourlifechoices.com.au/finance/seniors-finance/aussies-supporting-small-business