Each new generation of Australians since Federation has enjoyed a better standard of living than the one that came before it. Until now. Today’s young Australians are in danger of falling behind.

A new Grattan Institute report, Generation gap: ensuring a fair go for younger Australians, reveals that younger generations are not making the same economic gains as their predecessors.

Economic growth has been slow for a decade, Australia’s population is ageing, and climate change looms. The burden of these changes mainly falls on the young. The pressures have emerged partly because of economic and demographic changes, but also because of the policy choices we’ve made as a nation.

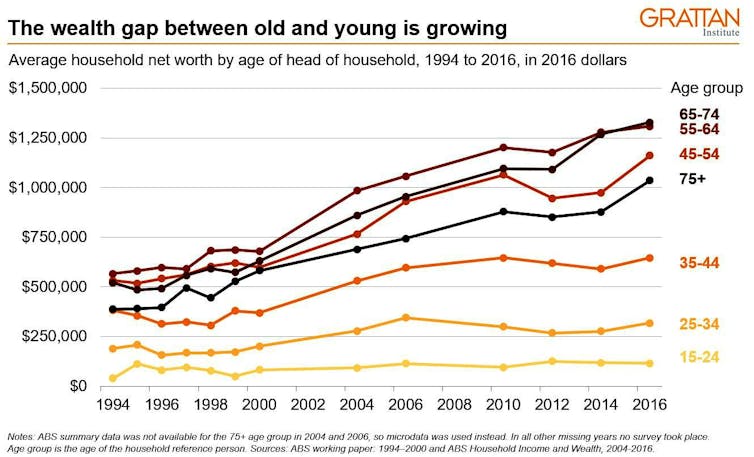

Older generations are richer than before, younger ones are not

For much of the past century, strong economic growth has produced growing wealth and incomes. Older Australians today have substantially greater wealth, income and expenditure compared with Australians of the same age decades earlier.

But, as can be seen from the yellow lines on this graph, younger Australians have not made the same progress.

The graph shows that the wealth of households headed by someone under 35 has barely moved since 2004.

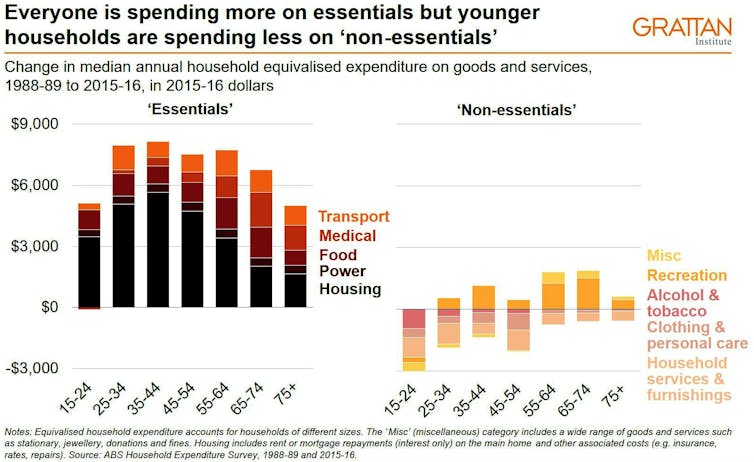

It’s not young people’s spending habits that are the problem – this is not a story of too many avocado lattes (and yes, they are a thing).

In fact, as the graph below shows, while every age group is spending more on essentials such as housing, young people are cutting back on non-essentials: among them alcohol, clothing, furnishings and recreation.

Wage stagnation since the global financial crisis and climbing underemployment have hit young people particularly hard. Older people tend to be better cushioned because they have already established their careers and are more likely to have other sources of income.

If low wage growth and fewer working hours becomes the “new normal”, we are likely to see a generation emerge into adulthood with lower incomes than the one before it.

It has already happened in the United States and United Kingdom.

Our generational bargain is at breaking point

Budget pressures will exacerbate these challenges.

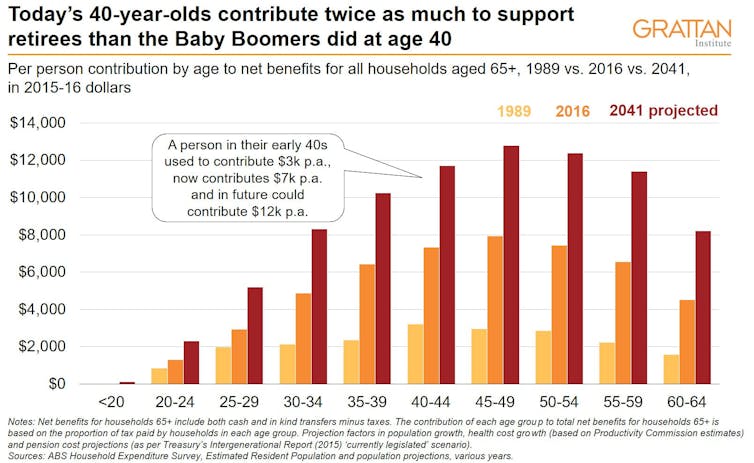

Australia’s tax and welfare system supports an implicit generational bargain. Working-age Australians, as a group, are net contributors to the budget, helping to support older generations in their retirement.

They’ve come to expect that future generations in turn will support them.

But Australia’s population is ageing – which increases the need for government spending on health, aged care and pensions at the same time as there are relatively fewer working age people to pay for it.

Demographic bad luck is one thing (some generations will always be larger than others) but policy changes are making the burden worse.

Read more: Expect a budget that breaks the intergenerational bargain, like the one before it, and before that

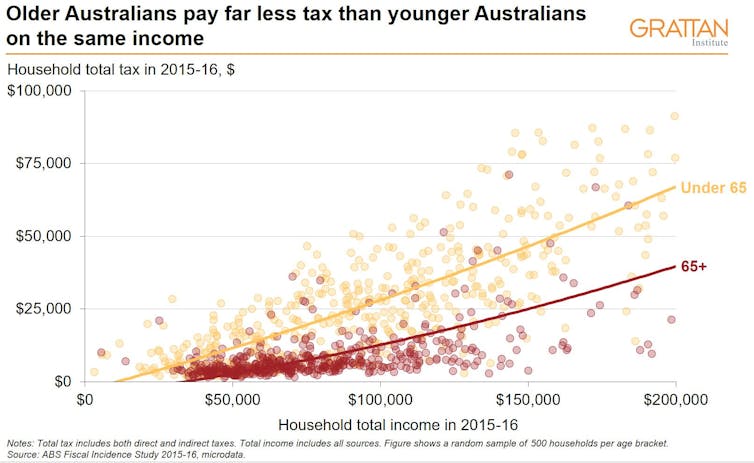

A series of tax policy decisions over the past three decades – in particular, tax-free superannuation income in retirement, refundable franking credits, and special tax offsets for seniors – mean we now ask older Australians to pay a lot less income tax than we once did.

Disturbingly, these and other changes mean older households now pay much less tax than younger households on the same income.

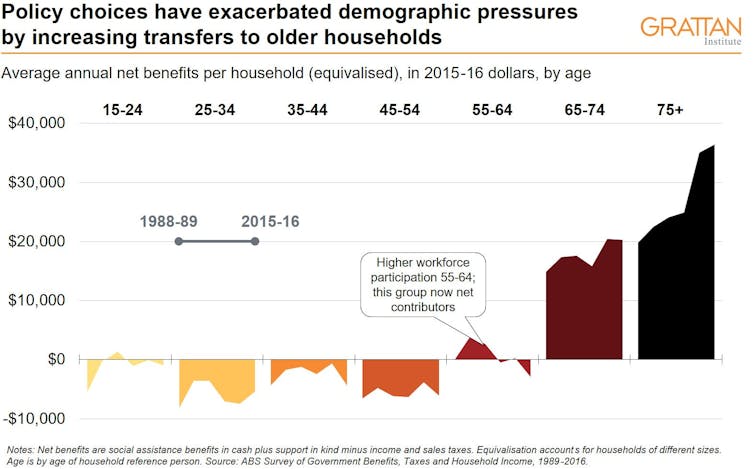

Added to this have been substantial increases in average pension and health payments for households over 65.

It has meant that net transfers – government benefits minus taxes – have dramatically increased for older households but not for younger ones.

The overall effect has been to make current working Australians increasingly underwrite the living standards of retirees.

A typical 40-year-old today contributes much more towards the retirement of others through taxes than did his or her baby boomer predecessors.

As it happens, it is also more than the typical 40-year-old is contributing to his or her own retirement through compulsory super.

This can’t be what Australians want

Most Australians want to leave the world a better place for those that come after them.

It’s time to make sure we do it.

Lots of older Australians are doing their best, individually, supporting their children via the “Bank of Mum and Dad”, caring for grandchildren, and scrimping through retirement to leave their kids a good inheritance.

These private transfers help a lucky few, but they don’t solve the broader problem. In fact, inheritances exacerbate inequality because they largely go to the already wealthy.

We need policy changes.

Reducing or eliminating tax breaks for “comfortably off” older Australians would be a start.

Read more: Migration helps balance our ageing population – we don’t need a moratorium

Boosting economic growth and improving the structural budget position would help all Australians, especially younger Australians. It would also put Australia in a better position to tackle other challenges that are top of mind for young people, such as climate change.

Changes to planning rules to encourage higher-density living in established city suburbs would help by making housing more affordable.

Just as a series of government decisions have contributed to the challenges facing young people today, a series of government decisions will be needed to help redress them.

Every generation faces its own unique challenges, but letting this generation fall behind the others is surely a legacy none of us would be proud of.

It’s time to share the burden, and perhaps an avocado latte while we’re at it.![]()

Kate Griffiths, Senior Associate, Grattan Institute and Danielle Wood, Program Director, Budget Policy and Institutional Reform, Grattan Institute

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Do you agree with these suggestions? Do you accept the notion that you had it better than younger generations? Is it fair to say that once super fully matures, the ‘burden’ of supporting retirees will ease? Have your say in the comments below.

If you enjoy our content, don’t keep it to yourself. Share our free eNews with your friends and encourage them to sign up.

Related articles:

Generation wealth gap widens

The fake intergenerational wars

Can Australia afford its retirees?