One of the paradoxes of retirement planning is that when making decisions about when to retire, it is typically financial considerations that take centre stage. After the event, it is more likely that non-financial considerations dictate whether one has a good retirement (underpinned by financials, of course).

These non-financial considerations merit much more extensive attention in public policy, media commentary, retirement transition planning and managing wellbeing in retirement.

Traditionally, commentary on retirement matters has been dominated by financial considerations, which are, of course, important. We are seeing a growing realisation that a whole host of non-financial considerations are arguably at least as important and, in aggregate, more important than financial considerations.

For many retirees, life after full-time work is very fulfilling, based on a naturally found balance of travel, leisure, family and friends, volunteering, community involvement, sports activities, etc. These people have got it sorted. For others, it can be a disruptive experience and a source of stress.

As well as losing our regular income, we potentially lose much more when we leave the workplace, including identity, purpose, structure, community, relevance and, for some, power. Without adequate planning and preparation, retirement can potentially be a disruptive and challenging experience with a significant detrimental impact on one’s mental health.

This planning and preparation for retirement – or, as we prefer to call it, ‘life after full-time work’ – on a holistic basis can better assure wellbeing in life after full-time work.

Holistic retirement planning

The critical elements of a successful retirement include financial, physical and mental health, along with a sense of purpose and identity. Any successful retirement planning approach needs to consider the whole person and not just the financial elements.

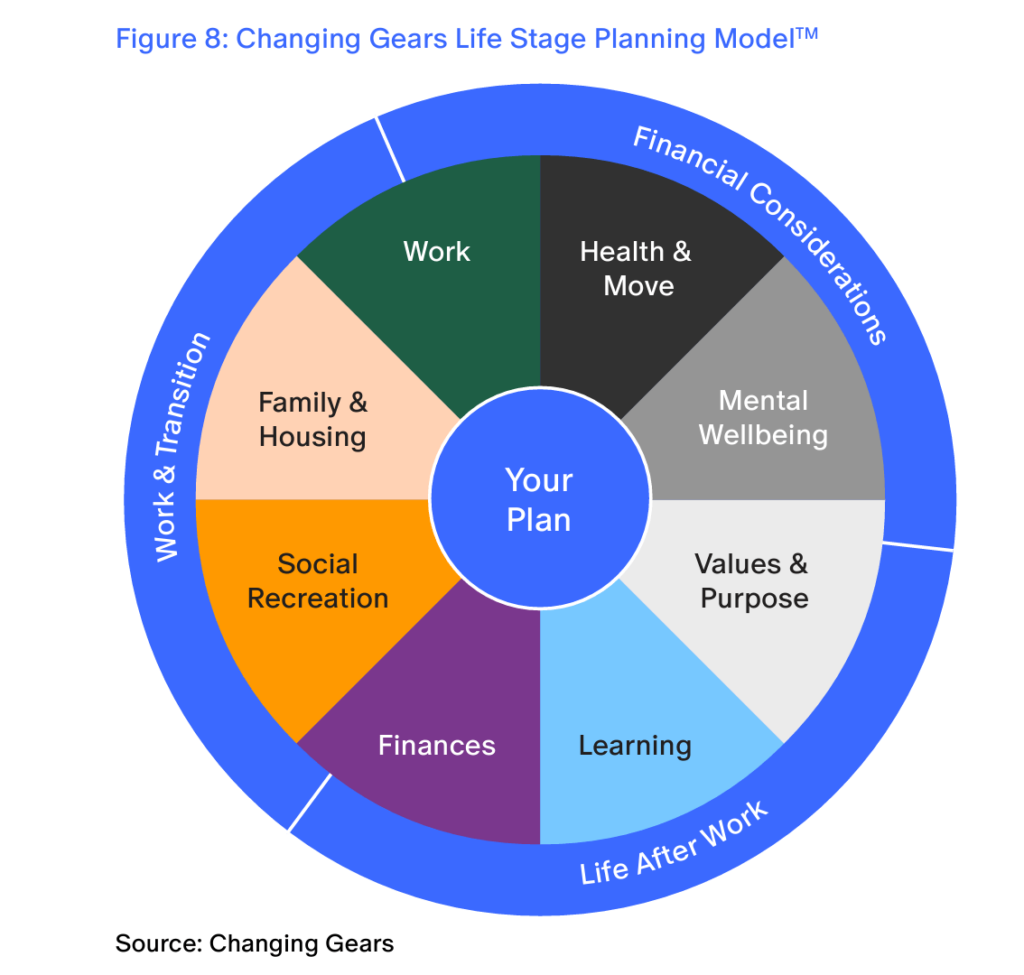

These non-financial considerations are not just ‘nice-to-have considerations’ and ‘add-ons’ to the retirement planning process. Those approaching retirement will benefit significantly from an integrated or holistic approach to retirement planning that covers both financial and non-financial dimensions. One such useful framework is the Changing Gears Life Stage Planning Model (see Figure 8 below).

Changing Gears has been applying this model for over 15 years to raise awareness and understanding of the issues to address in transitioning to retirement.

Other frameworks that emphasise the importance of a multi-dimensional and holistic approach include work by AgeWave and Edward Jones, which uses the four dimensions of health, family, purpose and finances, and the Victorian government’s Better Health Channel, which addresses post-work lifestyle, financial issues and retirement, emotional issues and retirement, and partner issues and retirement, and stresses that planning can help create a happy retirement.

Health trumps wealth

A significant component of the non-financial dimension in retirement planning must be planning around good health. As we have seen, the period of retirement is continuing to grow, and maybe it is helpful to talk about ‘rest-of-life’ planning or longevity planning.

Numerous studies have concluded that health is more important than wealth for retirees, including:

- “Retirees in better health experience greater feelings of wellbeing, including feeling more financially secure.” (MassMutual 2015)

- “81 per cent of retirees cite health as the most important ingredient to a happy retirement … Being financially secure was a distant second at 58 per cent,” according to an AgeWave study (McWhinnie, 2014).

Any considerations of health need to cover both physical and mental health. Retirement from full-time work can be a disruptive and difficult experience. It can be a time of emotional adjustment, and stress is not uncommon and may even manifest in retirement depression.

This can partly arise from the abrupt change to a sense of purpose and social relationships derived from work and work relationships. Robinson and Smith (n.d.) noted: “While retiring can be a reward for years of hard work, it can also trigger stress, anxiety and depression … Tips can help you cope with the challenges, find new purpose, and thrive in your retirement.”

Purpose, meaning and relationships

Meaning and purpose have a pivotal role to play in a successful life after full-time work. A major longitudinal study by Trinity College, Dublin, highlights the role of maintaining a healthy attitude as we age. Professor Rose Anne Kenny says: “We control 80 per cent of our ageing biology.”

Prof. Kenny’s research is complementary to the views of Moshe Milevsky, highlighting the need to think about ‘biological age’ versus ‘chronological age’.

Some of these phenomena are explained by epigenetics, which is the study of how your behaviours, attitudes and environment impact the functioning of your genes. Many epigenetic changes are reversible and, hence, manageable. (Dutchen, 2023)

Much has been written on the value of living life with a sense of meaning and its influence on wellbeing. This knowledge is especially important for retirement planning when our sense of meaning and purpose may have been strongly affiliated with the workplace.

Many have adopted the philosophy of Aristotle, who believed that happiness derives from living a life of meaning and that, conversely, “happiness is the meaning and purpose of life”. That is, they are mutually reinforcing.

Many will be familiar with the writings and thoughts of the eminent psychiatrist Dr Viktor Frankl and his book Man’s Search for Meaning (1946). He founded logotherapy, the central tenet of which is that the search for a life’s meaning is the central human motivational force.

A vital step in preparing for life after full-time work, or managing wellbeing in this stage of life, is identifying and fulfilling this meaning and purpose.

This will vary by individual and may include community involvement, serving a not-for-profit organisation with a worthwhile purpose, contributing to the growth and development of others (e.g. through mentoring), pursuing further education and learning, family commitments and involvement, religious or spiritual commitments, and so on.

“Having a purpose in life has been cited consistently as an indicator of healthy ageing for several reasons, including its potential for reducing mortality risk.” (Hill and Turiano, 2014)

Relationships rank at least as important as purpose and meaning. One of the most well-known studies into happiness is the Harvard Study of Adult Development. Its conclusion? “Positive relationships keep us happier, healthier, and help us live longer.”

Not only do relationships make us happier but the lack of relationships or loneliness can have quite detrimental effects on our physical health.

“The risk of premature death associated with social isolation and loneliness is similar to the risk of premature death associated with well-known risk factors such as obesity.” (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2015)

Failing to consider purpose, meaning and relationships can harm mental and physical health in retirement. “A common mistake in planning for retirement is not considering the emotional adjustment that occurs, which, in some cases, can cause depression.” (Iris Waichler, 2023)

“Unfortunately, all too many depressed older adults fail to recognise the symptoms of depression or don’t take the steps to get the help they need.” (Robinson et al., n.d.)

Ms Waichler also suggests a range of tips to manage this transition, including gradually transitioning out of full-time work (if one has that option), volunteering, preparation in advance, preparing your finances and destigmatising age (i.e. having a positive attitude to ageing and the impacts of epigenetics).

While some superannuation fund trustees are concerned about a potential conflict between the Member Best Financial Interest Duty and the types of support they can provide to members about their retirement (Hennington et al., 2023), we are pleased to see that some are providing guidance on non-financial aspects on their websites. We encourage more to do so.

Does the potential loss of a sense of purpose weigh on you or on your retirement plans? Do you have suggestions to work through this challenge? Share your thoughts in the comments section below.

Also read: What can you do to reduce retirement anxiety?

This article is from an Actuaries Institute dialogue paper titled Retirement Matters, written by actuaries Andrew Gale and Stephen Huppert. It is republished with permission.