The 4 per cent rule is a generally accepted rule of thumb to help retirees determine a safe level of annual income to ensure nest eggs last. But given the current environment of low interest rates and high equity valuations, it’s time to revise that rate. It’s also time to expand the retirement income toolbox, beyond this rule of thumb, to give the many Australians embarking on retirement the confidence to spend their hard-earned savings.

What is the 4 per cent rule?

Determining a safe level of annual income in retirement to avoid running out of money has been coined “the hardest, nastiest problem in finance” by Nobel laureate William Sharpe. Back in 1994, financial planner William Bengen conducted a study to find a starting withdrawal level (with the initial dollar amount adjusted thereafter for inflation) that could be sustained over every 30-year rolling time period since 1926. This was the genesis of the 4 per cent rule. It found that retirees invested in a balanced portfolio (an equal mix of stocks and bonds) could safely withdraw 4 per cent of their original assets, adjusted for inflation, for 30 years and not run out of money.

The 4 per cent rule is convenient and fits neatly into Australia’s financial planning infrastructure. It effectively takes an investment portfolio constructed for the saving (or accumulation) phase of retirement, tweaks the mix of stocks and bonds, and then ‘sets and forgets’ the level of spending each year. It keeps a very complex problem simple.

What’s wrong with the 4 per cent rule?

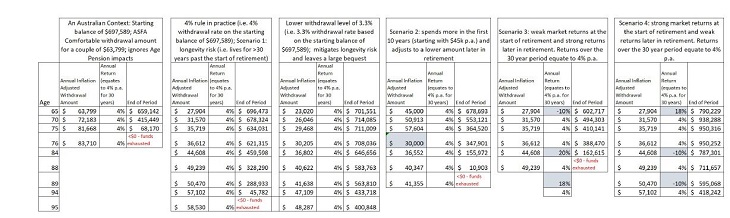

It’s too simple. It doesn’t optimise for a retiree who may: live for a shorter or longer period than 30 years (longevity risk); wish to spend more in the early years of retirement; is unable to stomach market ups and downs, or holds significant levels of home equity. Exhibit 1 demonstrates the outcomes of the first three scenarios using a very simplified set of assumptions in an Australian context. It ignores the impact of the Age Pension, which provides a safety net as superannuation savings and investment assets are consumed.

Exhibit 1: Simplified scenarios under the 4 per cent rule – an Australian context

While the Age Pension provides a significant safety net for retirees who desire income in excess of this minimum level, Exhibit 1 shows that the 4 per cent rule leaves retirees reliant on two main levers: market returns and spending levels. Granted, markets have done a stellar job underwriting most retirees’ spending, but their future path is unknown and not all retirees can tolerate market risk.

Read: Why retirement planning must be personal

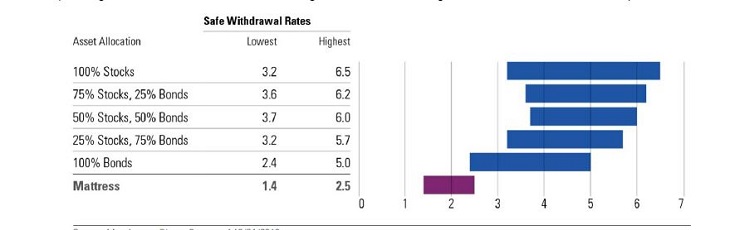

The problem with a rule of thumb is there is often a lot of variation for the individual experience and it doesn’t suit everyone. Morningstar’s US team recently conducted a study, The State of Retirement Income, which looked at the lowest and highest starting safe withdrawal rates over history using different mixes of stocks and bonds at a 90 per cent success rate. It found, in some periods, investors with a 50 per cent stock/50 per cent bond mix should have applied a 3.7 per cent starting withdrawal rate, and in other periods the rate could have been as high as 6 per cent.

Exhibit 2: Highest and lowest starting safe withdrawal rates, by asset allocation

Source: Morningstar Direct. Data as of 31/12/2019

The individual experience is always unique. If your starting withdrawal level is too low or you only live for part of the 30 years, you will underspend in retirement and likely leave a large (and possibly unintended) bequest. Conversely, if your starting withdrawal level is too high or you live longer than 30 years, there is the risk of running out of money.

Is the 4 per cent rule still valid?

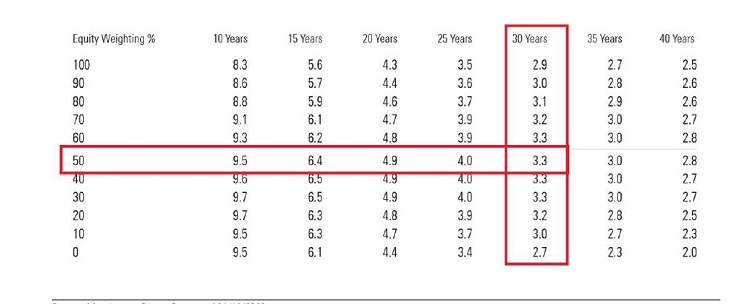

Morningstar’s US study challenged the validity of the 4 per cent rule and found that the level is too high in the current market environment. Instead, the research suggested that a starting fixed real withdrawal rate of around 3.3 per cent per year is more achievable for a portfolio invested in a mix of 50 per cent stocks and 50 per cent bonds for 30 years.

The study is US-centric, but the conclusions are broadly transferable. In a world of very low interest rates, it’s prudent to revise down the starting fixed withdrawal rate. And while a 0.7 per cent starting rate differential seems immaterial, the impact of compounding means that this could be the difference between relying solely on the Age Pension or living a more comfortable retirement.

Read: Are you retiring with more than you need?

Exhibit 3: Projected starting safe withdrawal rates, by asset allocation and time horizon

Beyond the 4 per cent rule – an expanded toolbox

While the 4 per cent rule has historically served many investors well, it isn’t perfect, and it isn’t for everyone. With the Retirement Income Covenant (RIC) looming, surely there are more tools available that can be employed to deliver effective retirement income strategies that give all retirees the confidence to spend their savings? Let’s take a look at a few.

Do annuities have a role to play?

There are two obvious use cases for annuities. First, annuities can provide income to cover basic needs. The Age Pension provides a stable income floor for many, but it doesn’t always cover your basic needs, with the maximum amount for couples just under $38,000 a year. The Association of Superannuation Funds of Australia (ASFA) estimates couples need about $41,000 annually to live a modest lifestyle. YourLifeChoices’ Retirement Affordability Index, developed with The Australia Institute and personalised across six cohorts, estimates a ‘constrained’ lifestyle for a couple would cost almost $45,000 per year.

There’s a gap here, particularly if you’re accustomated to a more comfortable lifestyle. A traditional (low-cost) lifetime annuity from an insurance company could cover this gap. Lifetime annuities come in different forms, but essentially they pay regular payments for life in exchange for a lump sum. The annuity income stream consists of the principal amount (which the investor paid upfront), the interest paid by the insurance company and the return available from pooling risk (such as mortality credits). Basically, those who die earlier than average subsidise those who live longer than average.

With low bond returns, these mortality credits provide an additional return source compared with traditional bonds. Second, deferred lifetime annuities might aid investors who believe they have adequate assets to fund themselves with certainty until a particular age; beyond that, they worry they will run out of money. A deferred lifetime annuity provides an effective way of managing the risk of living longer than you expect.

Annuities enable you to transfer some of the risk associated with achieving your retirement income goals and protect against market and longevity risk. But there are no free lunches and annuities have their own set of risks, one of which is that the insurance company can default. However, investors who are seeking certainty for a portion of their income should consider them.

Read: Seven out of 10 Aussies can retire sooner than they think: expert

The family home

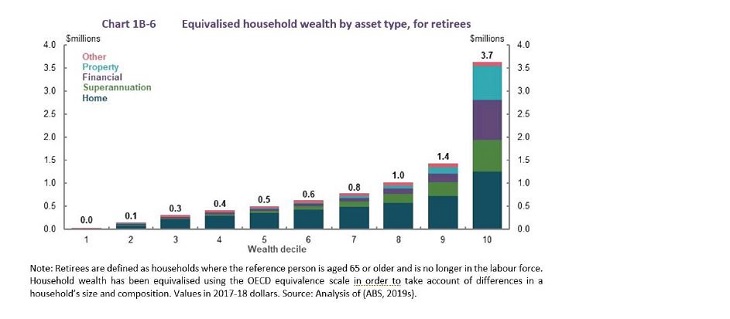

The family home remains a large proportion of household wealth (Exhibit 4). While downsizing and unlocking some of that wealth seems an obvious solution, many older Australians prefer to stay in their home. Retirees are also reluctant to supplement their retirement income through equity release schemes. However, the family home can’t be excluded from the toolbox. In fact, the government’s Equity Release Scheme has undergone some notable changes. For example, the interest rate has been lowered to 3.95 per cent and, subject to legislation passing in July 2022, a No Negative Equity Guarantee will be introduced.

Exhibit 4: Household wealth by asset type

Retirement Income Covenant-inspired tools

The advent of the RIC will inspire product innovation. Superannuation funds (many of them not-for-profit) with large pools of members are in a unique position to develop products, particularly those that derive value from risk-pooling. Some ‘retirement income-like’ solutions are already in the market, including Mercer LifetimePlus, QSuper Lifetime Pension and Magellan FuturePay. All are very different solutions, and one key challenge for investors will be comparing products and understanding whether they are right for them.

Bringing it all together

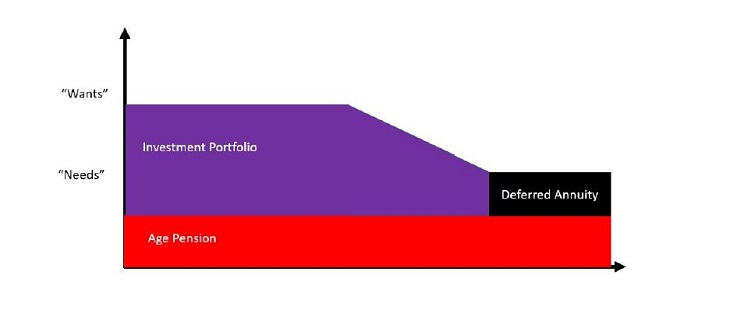

All investors have different preferences, risk tolerances and wealth levels and are willing to make different trade-offs. While rules of thumb are convenient, the reality is that different combinations of tools will best serve individual investors. Some investors will have a high risk tolerance and may prefer to rely on their portfolio and investment markets. Others will prefer an income-layering approach that uses a combination of tools (refer to exhibits 5 and 6). A key challenge is developing personalised strategies through more sophisticated online tools or better access to personalised advice.

Exhibit 5: Stylised example of income layering – home equity as a buffer

Exhibit 6: Stylised example of income layering – deferred annuities for longevity protection

Superannuation in Australia has focused on the saving phase of retirement and the (overly optimistic) 4 per cent rule has provided a neat extension to this phase. Markets have offered limited impetus for change.

However, the spending phase of retirement is complex and very different to the saving phase – there are many unknowns (market returns, longevity) and investors have unique preferences and tolerances. Therefore, new approaches to spending the nest egg are needed. The RIC provides an opportunity to break the nexus of the accumulation phase and develop more impactful tools, personalised strategies and financial-planning infrastructure to give retirees confidence to spend their savings.

Annika Bradley is director of Manager Research Ratings-Australia with Morningstar, a global provider of independent investment research. She is responsible for leading qualitative research on Asia-Pacific fund managers (excluding China, Hong Kong and Singapore) and their funds.

Copyright, disclaimer and other information: This report has been issued and distributed by Morningstar Australasia Pty Ltd ABN: 95 090 665 544, AFSL: 240892 and/or Morningstar Research Limited NZBN: 9429039567505, subsidiaries of Morningstar, Inc.

To the extent the report contains any general advice or ‘regulated financial advice’ under New Zealand law this has been prepared by Morningstar Australasia Pty Ltd and/or Morningstar Research Ltd, without reference to your objectives, financial situation or needs. For more information, please refer to our Financial Services Guide for Australian users and our Financial Advice Provider.

If you enjoy our content, don’t keep it to yourself. Share our free eNews with your friends and encourage them to sign up.