A challenge facing the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety will be to define ‘quality’.

Everyone has their own idea of what quality of care and quality of life in residential aged care may look like. The Conversation asked readers how they would want a loved one to be cared for in a residential aged care facility. What they said was similar to what surveys around the world have consistently found.

Characteristics that often appear as the basis for good quality of life include living in a home-like rather than an institutionalised environment, social connection and access to the outdoors. Good quality of care tends to focus on providing assistance that is timely and appropriate to individual needs.

Read more: Australia’s residential aged care facilities are getting bigger and less home-like

A bleak view of aged care

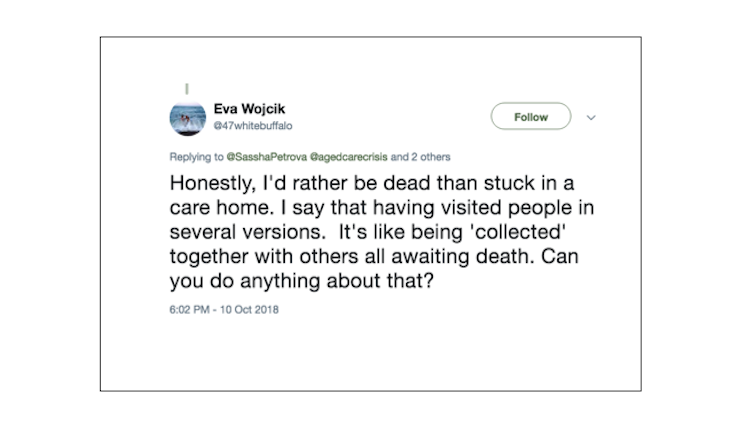

A mature judgement to determine good quality requires us to recognise that many people have an instinctive and distressingly bleak view of ageing, disability, dementia and death. Some people express this as death being preferable to living in aged care, as the tweet below shows.

This doesn’t necessarily reflect an objective assessment of the actual care being delivered in residential facilities, but it does speak to the fear of losing independence, autonomy and identity.

In a survey of patients with serious illnesses hospitalised in the US, around 30 per cent of respondents considered life in a nursing home to be a worse fate than death. Bowel and bladder incontinence and being confused all the time were two other states considered worse than death.

Aged care facilities will be the final residence for most before they die. This means the residents’ sense of futility and the notion one is simply waiting to die can and should be addressed.

Read more: How our residential aged-care system doesn’t care about older people’s emotional needs

Our reason for being is usually expressed through social connections. This is a recurring theme for residents who define quality of care as whether or not residents have friendships and are allowed reciprocity with their caregivers.

A systematic review that drew together a number of studies of quality in aged care found residents were most concerned about the lack of individual autonomy and difficulty in forming relationships when in care.

Good staff

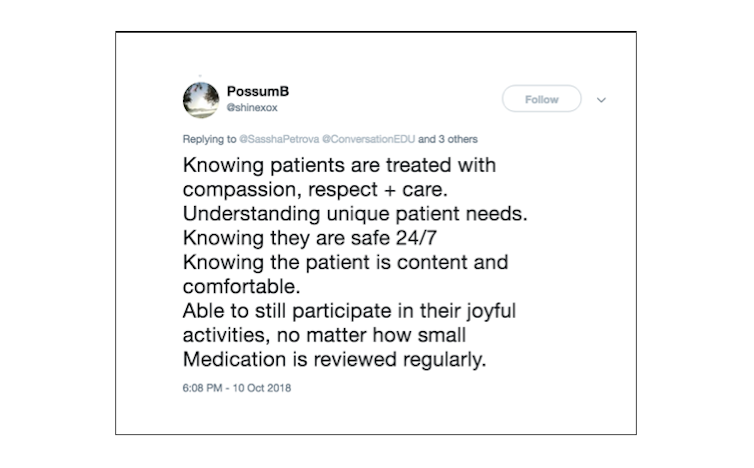

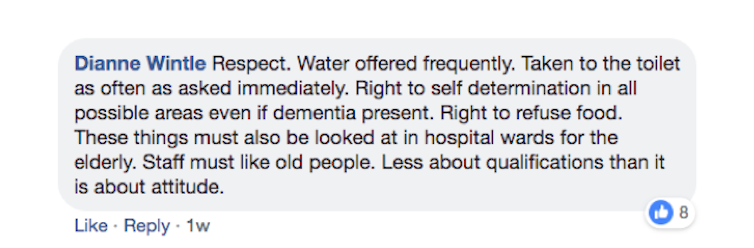

The need for positive social connections for residents extends to the relationships between staff and families. Achieving this requires staff with a positive attitude who work to build trust and involve family in their loved one’s care. They must also engage on issues that have meaning to the individuals.

Good staff should be both technically proficient and, perhaps more importantly, good with people.

Dianne Wintle comment. Facebook screenshot

Dianne Wintle comment. Facebook screenshot

Idyllic, or the way it should be?

A home-like setting – which may include having a pet and enjoying time in nature, as the tweet below describes – may seem idyllic. However, more contemporary models of care are moving towards smaller home-like environments that accommodate fewer people and are more like a household than a large institution.

The ability to relate and personalise care to a small group of 10-12 residents is surely easier than catering to 30-60 residents. Some studies in the US have shown residents in such smaller units have an enhanced quality of life that doesn’t compromise clinical care or running costs.

Read more: Caring for elderly Australians in a home-like setting can reduce hospital visits

This cluster-style housing still has limitations that need to be addressed. These include selecting residents who are suitable together and catering for the changing clinical and care needs of each individual.

Pets and the outdoors

Research into the value of pets in aged care has largely focused on the benefits to people living with dementia. Introducing domestic animals, typically dogs, has been shown to have positive effects on social behaviours, physical activity and overall quality of life for residents.

Similarly, providing accommodation where the physical environment and building promote engagement in a range of indoor and outdoor activities, and allow for both private and community spaces, is associated with a better quality of life.

Good food

Another major determinant of quality of life in residential aged care is the quality of food. This becomes even more important as people age. Providing high-quality food and enriching meal times is more challenging as many diseases such as dementia and stroke affect older people’s dentition and swallowing.

Aged care services need proactive and innovative approaches to overcome these deficits and better promote general health.

A key feature often overlooked is the cultural significance of food. Providing traditional foods to residents strengthens their feeling of belonging and identity, helping them hold on to their cultural roots and enhance their quality of life.

Safety, dignity, respect and choice

While the focus is often on preventing abuse, neglect and restrictive practices in aged care, the absence of these harmful events doesn’t equate to a positive culture. Residents want and have a right to feel safe, valued, respected and able to express and exercise choice. Positive observation of these rights is essential for quality of life.

Clinical and personal care

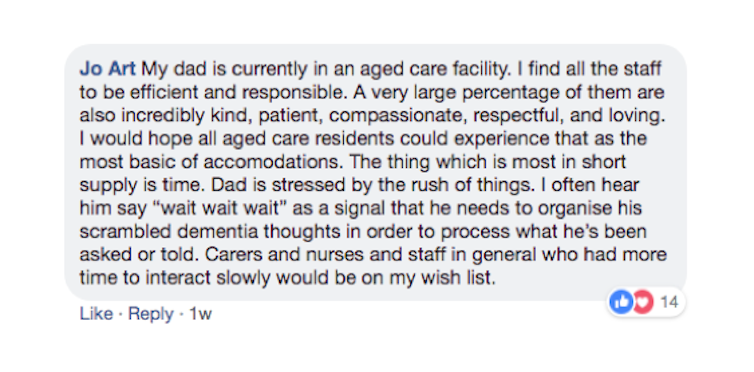

Time is a factor in aged care, as staff often don’t have enough time to spend with each resident. A recent ABC Four Corners investigation into quality in aged care found personal care assistants had only six minutes to help residents shower and get dressed. No wonder, then, that staff often don’t have the personal time to be able to spend with residents who need life to be a little slower, as the Facebook comment below shows.

Clinical care is another important aspect of quality aged care. A resident cannot enjoy a good quality of life if their often multiple and chronic conditions such as diabetes, heart failure and arthritis are poorly managed by their doctors and nurses.

Read more: Australia’s aged care residents are very sick, yet the government doesn’t prioritise medical care

Residents in aged care are the same as those who live in the community. They are people with the same needs and wants. The only difference is they need the community to give the time, effort and thought to achieve a better life.![]()

Joseph Ibrahim, Professor, Health Law and Ageing Research Unit, Department of Forensic Medicine, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Related articles:

The power of cuddle therapy

Eat your way to good health

Can crying make you feel better?