Mohiuddin Ahmed, Edith Cowan University and Paul Haskell-Dowland, Edith Cowan University

Over the past 25 years, the name ‘Google’ has become synonymous with the idea of searching for anything online. In much the same way ‘to Hoover’ means to use a vacuum cleaner, dictionaries have recognised “to Google” as meaning to undertake an online search using any available service.

Former competitors such as AltaVista and AskJeeves are long dead, and existing alternatives such as Bing and DuckDuckGo currently pose little threat to Google’s dominance. But shifting our web searching habits to a single supplier has significant risks.

Google also dominates in the web browser market (almost two-thirds of browsers are Chrome) and web advertising (Google Ads has an estimated 29 per cent share of all digital advertising in 2021). This combination of browser, search and advertising has drawn considerable interest from competition and antitrust regulators around the world.

Leaving aside the commercial interests, is Google actually delivering when we Google? Are the search results (which clearly influence the content we consume) giving us the answers we want?

Advertising giant

More than 80 per cent of Alphabet’s revenue comes from Google advertising. At the same time, around 85 per cent of the world’s search engine activity goes through Google.

Clearly there is significant commercial advantage in selling advertising while at the same time controlling the results of most web searches undertaken around the globe.

This can be seen clearly in search results. Studies have shown internet users are less and less prepared to scroll down the page or spend less time on content below the ‘fold’ (the limit of content on your screen). This makes the space at the top of the search results more and more valuable.

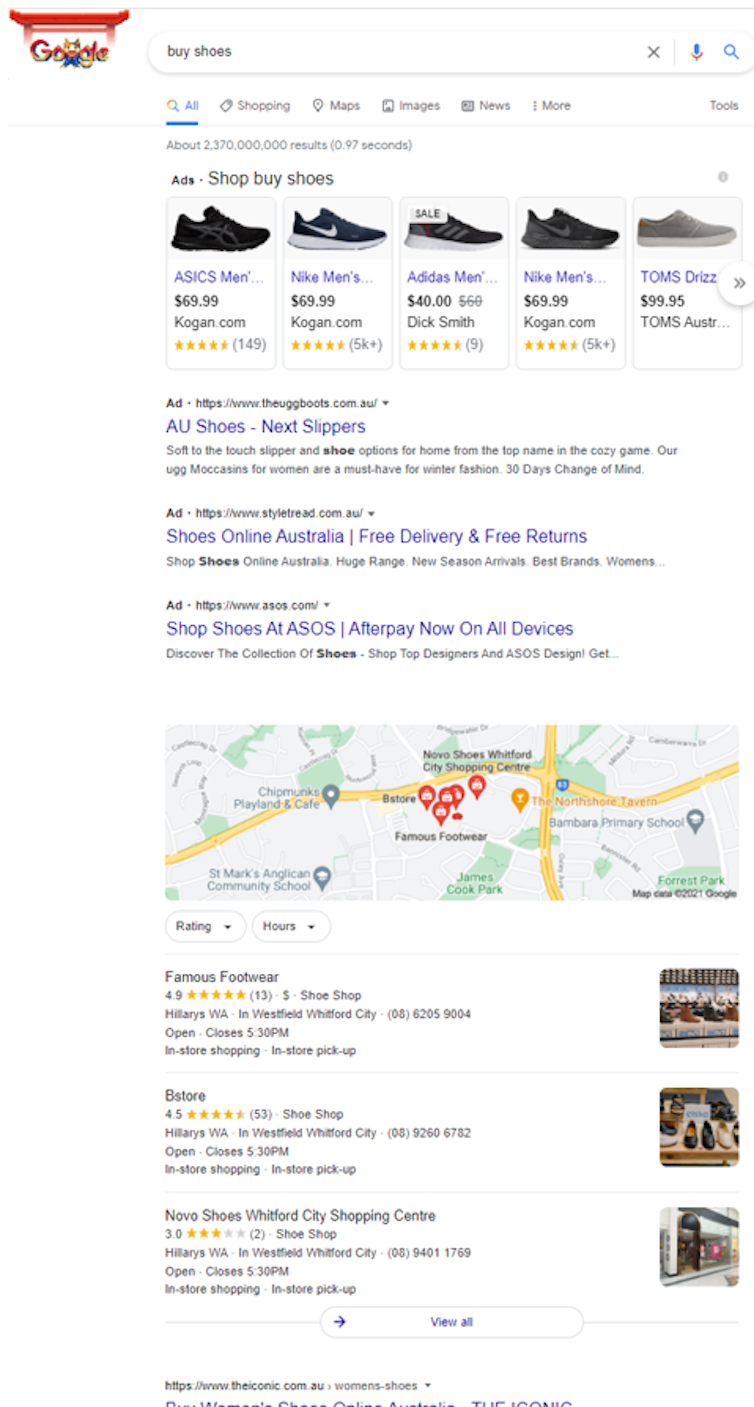

In the example below, you might have to scroll three screens down before you find actual search results rather than paid promotions.

Author provided

While Google (and indeed many users) might argue that the results are still helpful and save time, it’s clear the design of the page and the prominence given to paid adverts will influence behaviour. All of this is reinforced by the use of a pay-per-click advertising model that is founded on enticing users to click on adverts.

Annoyance

Google’s influence expands beyond web search results. More than two billion people use the Google-owned YouTube each month (just counting logged-in users), and it is often considered the number one platform for online advertising.

Although YouTube is as ubiquitous to video-sharing as Google is to search, YouTube users have an option to avoid ads: paying for a premium subscription. However, only a minuscule fraction of users take the paid option.

Evolving needs

The complexity (and expectations) of search engines has increased over their lifetime, in line with our dependence on technology.

For example, someone trying to explore a tourist destination may be tempted to search “What should I do to visit the Simpsons Gap“.

The Google search result will show a number of results, but from the user perspective the information is distributed across multiple sites. To obtain the desired information users need to visit a number of websites.

Google is working on bringing this information together. The search engine now uses sophisticated ‘natural language processing’ software called BERT, developed in 2018, that tries to identify the intention behind a search, rather than simply searching strings of text. AskJeeves tried something similar in 1997, but the technology is now more advanced.

BERT will soon be succeeded by MUM (Multitask Unified Model), which tries to go a step further and understand the context of a search and provide more refined answers. Google claims MUM may be 1000 times more powerful than BERT, and be able to provide the kind of advice a human expert might for questions without a direct answer.

Are we now locked into Google?

Given the market share and influence Google has in our daily lives, it might seem impossible to think of alternatives. However, Google is not the only show in town. Microsoft’s Bing search engine has a modest level of popularity in the United States, although it will struggle to escape the Microsoft brand.

Another option that claims to be free from ads and ensure user privacy, DuckDuckGo, has seen a growing level of interest – perhaps helped through association with the TOR browser project.

While Google may be dominating with its search engine service, it also covers artificial intelligence, healthcare, autonomous vehicles, cloud computing services, computing devices and a plethora of home automation devices. Even if we can move away from Google’s grasp in our web browsing activities, there is a whole new range of future challenges for consumers on the horizon.

Read more:

Robot take the wheel: Waymo has launched a self-driving taxi service

![]()

Mohiuddin Ahmed, Lecturer of Computing & Security, Edith Cowan University and Paul Haskell-Dowland, Associate Dean (Computing and Security), Edith Cowan University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.

Have you noticed it is getting harder to find what you want when you search for something on Google? Why not share your thoughts in the comments section below?

If you enjoy our content, don’t keep it to yourself. Share our free eNews with your friends and encourage them to sign up.