These days there aren’t many people left who would argue against solar power being part of Australia’s energy future. Just how big a part remains the fodder for media (mainstream and social) debate. It’s a debate also used to score political points.

I’m happy to leave that debate to neutrals who have the scientific and economic expertise to make the right call. However, one aspect of solar power that is becoming increasingly harder to ignore is the issue of solar waste.

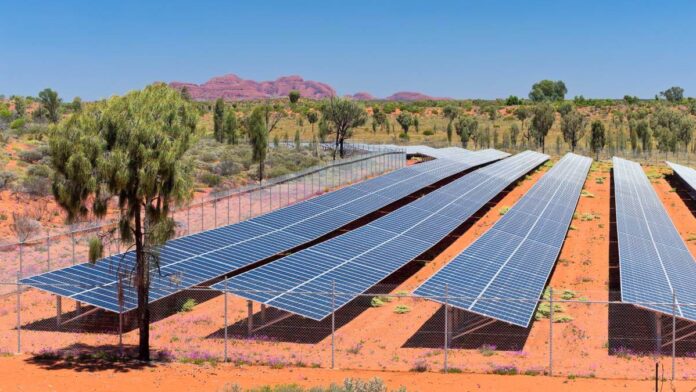

The sun is a magnificent and limitless (at least in human terms) source of energy for all. But capturing, converting and storing that energy does require some hardware. And now that solar energy has been in common use for decades, time is up for some of that hardware.

A lot of it, in fact. The question is, now that those solar panels have given us their all, what should be done with them? After all, one of the aims of using solar power is to help the planet. And we know that landfill certainly doesn’t help achieve that aim.

Now that older generation solar panels are reaching their end of life, solar panel waste is becoming a big issue. In fact, we are rapidly approaching a tipping point, according to one expert.

Solar power in crisis?

In a white paper tabled last week, lead author Rong Deng outlined the major issues at hand. And the landfill aspect of disposing of solar power waste is only one side of the equation. Mr Deng, a renewable energy engineering researcher at the University of NSW, warned of the consequences of upscaling.

It’s been an aim of many to expand the production of solar panels by five to 10 times, he said. But if we achieve that aim, said Mr Deng, “we will run out of the world’s reserves of silver in just two decades”.

Silver isn’t just used to make jewellery. Among other things, it is used in the fields of medicine, electronics, toolmaking and photography. And, as we now know, in the manufacture of solar power. So it would not be in our best interests to run out of it.

Mr Deng describes the design of solar panels as akin to a “fused, watertight, weatherproof sandwich”. Making that sandwich entails extracting valuable materials, such as silicon, silver and copper. Turning those materials into usable components is difficult, Mr Deng said.

So what’s the solution?

Identifying and planning that solution is what Mr Deng’s white paper sets out to do. The result is a 12-year industry roadmap for solar power and specifically solar panels.

There are two major areas of focus. Firstly, developing sophisticated technologies to extract valuable metals. These will go a long way towards averting any crises, such a shortage of silver. Secondly, achieving that primary aim will require the procurement of old solar panels. That means efficient recycling processes. Achieving that will require the establishment of recycling centres across metropolitan areas and developing a product stewardship scheme for photovoltaics.

Sounds good – when can we start?

Surprisingly, the answer to that is very soon. The product stewardship scheme will be introduced next year. The scheme could mandate recycling, or penalise not recycling, the paper suggests. It could also make solar panel manufacturers financially responsible for the disposal of end-of-life panels. The prospect of saving money is a great incentive for most profit-driven organisations, so that’s probably not a bad idea.

It sounds like Australia has taken some good early steps to averting a solar power crisis. What it needs now, says another industry expert, is government funding.

That expert is Richard Kirkman, chief executive of energy and waste recycling management service Veolia Australia and New Zealand. Mr Kirkman says federal funding pilot projects could ensure solar panels were designed to be easy to recycle. The next step would be to develop large-scale recycling processes.

“If we get this right we can close this loop in a way that will underpin the Australian way of life for generations with the recovery and recycling of the precious metals and rare earths inside discarded end-of-life panels,” Mr Kirkman said.

That will help provide a sunny future for all Australians.

Does your property use solar power? How far into their lifespan are your solar panels? Let us know via the comments section below.

Also read: Take back control of your energy-sucking kitchen appliances

What about the windmills. Where do they get recycled. No one wants to talk about it.

The windmills can be recycled and some are. Until very recently there were not enough discarded wind turbines to set up recycling for and they were being dumped.

That is now changing as increasing numbers make recycling economically viable.

I am not aware of much recycling of retired coal and nuclear plants either.

David, fortunately at this stage in Australia, there is little call for the recycling of wind turbines, but a number of aspects are known.

Firstly, the turbine blades cannot be recycled. The manner of their construction does not give anything of value for recovery and reuse.

Yes, there are a lot of valuable metals in the generator pod. But can they be economically removed from the site and parted out for recovery of those metals? In many areas, no. A fully assembled pod weighs around 200 tonnes. Bringing them down without damage comes at significant cost (Estimated to be up to $100K.) The further cost of transport to a recycling centre may make that uneconomic.

Remember that the typical contract life of a wind or solar farm is 20 years. So you will see an endless procession of replacement. A typical coal and nuclear power station has been shown to be around 60 years. One average nuclear power station provides the equivalent power of upwards of 2,000 wind turbines. You can see immediately the the bulk of waste from wind is far greater than from a nuclear power station. And from the essential power to the Grid, wind cannot stand on it’s own but requires as a minimum equivalent power from solar plus equivalent again in storage such as batteries which also have a very limited life of under 20 years before they must be discarded. The present battery chemistry is not suitable for cost effective recovery and may not be for decades to come.

The inescapable superiority of coal and nuclear is that they have a delivery factor of over 90% while solar is under 25% and wind ~30%. Coal and nuclear have proven to be able to meet Grid demand 24 hours a day, for 365 days a year with great predictability. Something that no renewable system in Australia can come close to and cannot without extremely expensive backup systems.

When Mr Deng refers to silver reserves, exactly what is he referring to? Silver presently refined and available for industry? Mined and awaiting refining? Or potential estimated unmined ore reserves?

The Australian Federal Government has very recently signed an MOU with a company to establish a factory in the Hunter Valley that claims to have evolved a new technology photovoltaic cell that is upwards of 20% more efficient than the legacy silver based cells and doing it using copper. This MOU is worth $1billion with the hope that they can manufacture these new cells for export into the world market.

If they can get them to work as promised, the demand for silver may well plateau and maybe even decline once the production has been licensed to China.

Among the unknowns with these new cells is their durability. Present high quality photovoltaics are claiming within 80% on new for at least 20 years. Lesser quality panels have been found to drop below this within 15 years.

Todate, the only examples of recovery of the metals from out of time photovoltaics appear to have been running on Government Grants and Research funding with claims that there will be a market for the fine mix of silica, resins and metals. While the metals can be economically sourced from new ore, there will be little to no market for recovery and recycling of old cells and they will discarded to landfill.