Violetta Wilk, Edith Cowan University

It’s a simple building. A shed, really. You can’t go inside, and even if you could, there’s nothing in there. For decades it was derelict, an eyesore to which locals paid little attention.

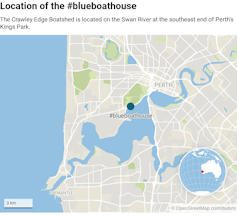

But this humble boat shed, on the shore of the Swan River in Perth, Western Australia, has become a social media superstar. Known around the world simply as the #blueboathouse, since being restored in the early 2000s it has become Perth’s second-most popular spot for tourist selfies.

On Instagram there are now more than 15,000 #blueboathouse-tagged posts. That’s still less than half the 81,000 posts for Elizabeth Quay, the city’s purpose-built entertainment and leisure precinct, but the quay did cost the state government A$440 million to build, compared with nothing for the privately owned boat shed.

The Conversation

It will, though, now cost Perth’s city council A$400,000 to build a public toilet near the boat shed, due to the sheer volume of Insta-happy visitors. An Insta-toilet, if you will.

In terms of value for marketing dollars, it’s a bargain.

Between Instagram, Twitter, Facebook, Tripadvisor and other social media, the #blueboathouse has generated global awareness about Perth potentially worth millions of dollars. Tourism advertising gurus could brainstorm for months and not come up with something as cheap or effective.

It signifies the profound effect that social media is having on consumer markets, the rise of organic marketing and the phenomenon of “unpaid influencers”.

romart_photography/Instagram.com

The rise of the unpaid influencer

As a researcher, I am fascinated by this phenomenon, which sees everyday consumers (tourists, in this case) become advocates for the brands or destinations they have experienced. In marketing we call them “online brand advocates”. They are a brand’s most authentic marketing investment.

Tourism provides a textbook example of the way social media is blurring the boundary between media use and marketing. With the selfie now the virtual vehicle for instantly sharing holiday happy snaps and proving “I was there”, platforms such as Instagram have become powerful dictators of what’s hot. Each day Instagram users post 95 million photos and videos. Some of these posts, bound by a hashtag, inspire emulation.

Selfie-taking has been embraced by Asian cultures. Chinese and Japanese social media users refer to “ASS” – Asian Selfie Spots. Becoming recognised as such a spot can be a transformative experience for a local economy.

Read more: #MeTourism: the hidden costs of selfie tourism

But wait, you ask, has the chance to visit a boat shed really led someone in, say, Beijing, to book a ticket to Perth rather than Las Vegas?

Another unlikely Asian Selfie Spot in Australia suggests it might have.

This is Sea Lake, in northwest Victoria.

It is one of the state’s most isolated towns, and also one of its smallest, with a population of about 600. Its name comes from the nearby Lake Tyrrell, which most of the year is effectively a salt lake.

For most the year Lake Tyrrell is dry. www.shutterstock.com

Until a couple of years ago, Sea Lake was not on anyone’s list of must-visit locations.

But then some photos of what happens in winter, when the shallow, salty depression of Lake Tyrrell is covered in a few centimetres of water, changed all that.

Lake Tyrrell when covered in water. www.shutterstock.com

A trickle of Chinese tourists turned into a relative flood, inspiring new investment and an economic boost for a drought-stricken community in decline.

Seeking authenticity

The influence of platforms like Instagram was recognised reasonably quickly by commercial interests. It led to a whole new industry of “influencers” – social media personalities with large followings who take cash or gifts to promote brands. Sometimes they are upfront about the fact they are being paid to spruik products; sometimes they are not.

The influencer market worth is difficult to calculate, and 2020 predictions range anywhere from US$2.3 billion to US$16.6 billion.

But even as it is reportedly growing exponentially, there’s also a growing feeling that the paid-influencer market is perverting what social media is meant to be about – engagement with authentic storytelling. Instagram has recognised this shift and earlier this year trialled removing “likes” and follower numbers as a means to limit people cashing in on their popularity.

Read more: Why do people risk their lives for the perfect selfie?

Against the paid influencers, we see the rise of the unpaid influencers. They generate organic, authentic social media exposure; and because they’re just like you or me (they might even be you or me) they’re highly relatable and trustworthy.

More and more they inform the decisions we make, from choosing a restaurant to booking a holiday.

So perhaps take another look at that local derelict building or dried-up lake. You never know, it might just be a future tourist hotspot waiting to happen.![]()

Violetta Wilk, Lecturer & Researcher in Digital Marketing, Edith Cowan University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

If you enjoy our content, don’t keep it to yourself. Share our free eNews with your friends and encourage them to sign up.

Related articles:

Scary Australian attractions

Most disappointing attractions

How to skip the line at attractions