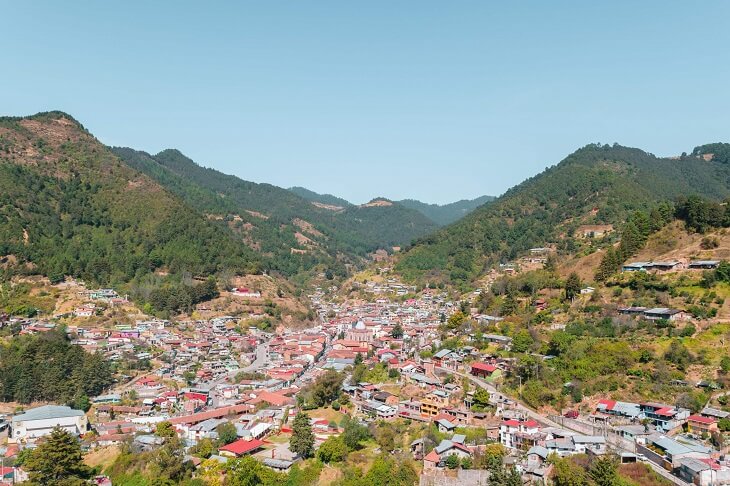

Fluttering above the terracotta roofs of Angangueo, a former mining town in central Mexican state Michoacán, millions of wings beat and settle like flakes of amber snow.

“Our ancestors thought they were spirits,” explains my guide Hernando, as the ethereal beings float into the folds of forest-cloaked mountain slopes. “I remember when my mother died; a butterfly appeared the following day.”

It’s understandable why local people might interpret this mass migration as a visit from the other side; the monarchs’ arrival every year happens around the beginning of November, when Mexicans honour their dearly departed during El Dia De Los Muertos (Day of the Dead).

Like clockwork, masses of the elegant insects leave their birthplaces along the US and Canadian border, although it wasn’t until 1975 that scientists realised they were coming here, to a small patch of fir forest, nearly 3000 metres above sea level.

Travelling for an incredible four months, they cover 5000km for a gathering that’s the equivalent of a music festival in the entomologist’s world.

Distinguishable by their polka dot-fringed tangerine wings, monarch butterflies can be found in many countries, but these are the globetrotters, the only ones that travel so far.

Stopping at the base of El Rosario, part of the Reserva Mariposa Monarca (Monarch Butterfly Reserve) which is open to the public, we swap our four wheels for horses, and climb higher into the Oyamel fir forest.

Read: Sir David’s animal magic

I’m visiting at the end of March, when most butterflies have left, but I’m still showered by petals of animated confetti, even though local guide Silvestre informs me this is just 25 per cent of the 150 million that annually descend.

Most butterflies live for 25 days but one generation, the Methuselah, can survive for up to nine months – the equivalent, in human terms, of 525 years. These are the intrepid adventurers able to travel from North America to Mexico and back.

The secret to their longevity is still a mystery, although one theory suggests it’s all in the birth date; emerging from their chrysalis at the end of August (when temperatures are falling and days are shorter), they slip into a state of semi-hibernation, slowing down bodily functions and storing energy for a longer life.

And the science of their internal compass is an even greater enigma, because no single butterfly makes this astounding migration twice.

Silvestre has been working at El Rosario for 17 years and he doesn’t know the answer, but he’s still staggered by the phenomenon year after year.

Other local residents, however, didn’t always feel that way.

Read: World’s best wildlife trips

“Some people thought they were a plague,” he tells me as we perch on fallen logs in a sun-splintered clearing. “They used to fry the butterflies, remove any poisonous parts and eat the rest in tacos.”

A greater death threat came in 2010, when North Americans destroyed fields of milkweed – a favourite food for monarch caterpillars – resulting in the population’s drastic decline. In 2014, the presidents of Canada, USA and Mexico agreed the conservation of butterflies was a priority, and Silvestre assures me numbers have risen since then.

Noise upsets the butterflies, so we sit in silence and listen to the sound of beating wings trickling like raindrops, even though the air is bone dry.

In shady areas, clusters keep warm by clinging to tree trunks, transforming the forest into a mass of reptilian scales. And above us, wings bluster like autumn leaves across the blue sky, their shadows dancing at my feet.

Some will return home, others will stay, spiralling to the ground now their time is up.

And so the cycle of life continues, an epic migration and a journey with no beginning or end.

Read: 101 ways to holiday in Australia: Connect with wildlife

Three other great wildlife migrations around the world

Wildebeest

Following the rains and opportunities for grazing, East Africa’s wildebeest lead a nomadic lifestyle year-round. The most impressive section of their journey occurs in Kenya’s Maasai Mara, when millions of the gnus make treacherous river crossings in croc-infested waters, creating an explosion of dust and deathly cries. Thousands of tourists line up to see the spectacle, which reaches a peak in August and September – although recent changes in weather patterns have made the phenomenon a little harder to predict.

Black-necked cranes

Famous for their high-altitude flight patterns, these endangered birds spend summers breeding on the Tibetan Plateau. Between October and mid-February, they flock to Bhutan’s Phobjikha Valley, where local people celebrate a festival in their honour. The event coincides with the king’s birthday and is held every year on 11 November.

Bats

The sky turns black at the height of Zambia’s great bat migration, when large colonies of fruit bats arrive at Kasanka National Park. They come at the end of October in search of seed-rich fruits growing in the swamp lands, with up to eight million occupying a hectare of land until early January.

Have you witnessed an animal migration? Which would you most like to see in person? Let us know in the comments section below.

– With PA

If you enjoy our content, don’t keep it to yourself. Share our free eNews with your friends and encourage them to sign up.